- Philharmonic Moments

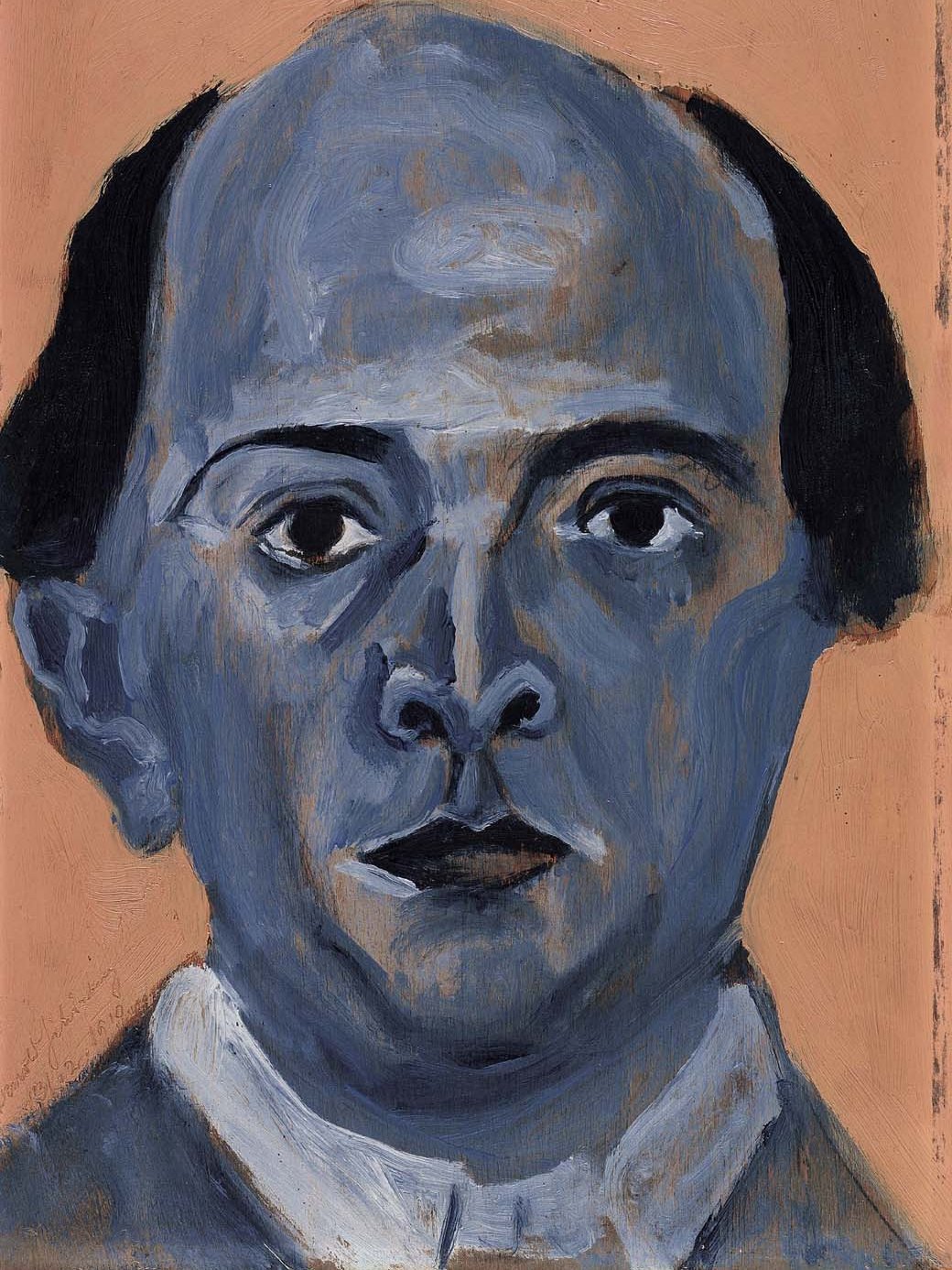

They are among the most demanding ever composed for a large symphony orchestra: Arnold Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra op. 31. The epochal work is once again on the programme of the Berliner Philharmoniker with Kirill Petrenko. The premiere in Berlin under Wilhelm Furtwängler in December 1928 however turned into a fiasco.

Arnold Schoenberg hated revolutions, even musical ones. He didn’t claim to have initiated a break in music history with his twelve-tone method, but saw himself as continuing and perfecting the classical tradition. This rather bold self-assessment developed into the credo of German musicology in the following decades. But there were also opposing voices that could not be dismissed as statements of incorrigible reactionaries. The most notable critic was Wilhelm Furtwängler.

His authority was great even in the circle of Schoenberg’s followers, as – despite aesthetic reservations – the Berlin conductor had presented works by the Viennese composer on several occasions. He respected Schoenberg, who had been teaching at the Prussian Academy of Arts since 1925, and supported him in many ways; Schoenberg, for his part, revered Furtwängler throughout his life as the century’s leading conductor.

There were certainly similarities between these two very dissimilar spiritual brothers. Both Schoenberg and Furtwängler saw German music as the pinnacle of the Western tradition – and they believed in a productive continuation of this tradition which stretched back as far back as Bach. As a result, Furtwängler frequently devoted himself to composers as diverse as Hans Pfitzner, Max Trapp, Günter Raphael, Heinrich Kaminski, Ernst Pepping and Karl Höller; because of Paul Hindemith, he even provoked a confrontation with the Nazis in 1934 and resigned from all his posts when his demands were not met. But the chief conductor of the Berliner Philharmoniker and the Leipzig Gewandhaus was also committed to numerous foreign contemporaries, among them Stravinsky, Respighi, Bartók, Ravel and Honegger – and dared to put Chopin on a par with Bach.

For the supremacy of German music

Such views were far from Arnold Schoenberg’s thinking. In a letter to Alma Mahler, written a few days after the outbreak of war in 1914, he confessed: “I have never had much use for any foreign music. It always seemed to me stale, empty, disgustingly cloying, dishonest and incompetent. Without exception [...] This music had long since been a declaration of war, an attack on Germany”. Unexpectedly, world history now provided the neo-Teuton with the means to thoroughly purge the country: “But now comes the reckoning!” Schoenberg rejoiced, “Now we will throw these mediocre, kitschy composers back into slavery and they shall learn to revere the German spirit and worship the German God”.

He was not alone in such views – think of Thomas Mann’s Thoughts in War or his Reflections of a Non-political Man. As late as 1921, Schoenberg told his pupil and later assistant Josef Rufer that the twelve-tone technique would “secure the supremacy of German music for the next hundred years”. As is well known, this didn’t happen. Furtwängler was actually only interested in Schoenberg’s early works, especially Verklärte Nacht and Pelleas und Melisande, but he had already performed the atonal Five Pieces for Orchestra op. 16 in Berlin in 1922.

The high point of their collaboration was then the Variations for Orchestra op. 31, whose world premiere Furtwängler conducted on 2 December 1928 – despite some reservations about the twelve-tone technique which is rigorously applied here.

In particular, he criticised the dogma of Schoenberg’s circle that dodecaphony was the logical culmination of tonal development – it was rather, according to Furtwängler as late as 1945, “the first completely unhistorical step, the first real break with history”.

Why then did he devote himself to this work? Was it because he felt obliged to present even those pieces that ran counter to his aesthetic feeling, his fundamental convictions? Perhaps it also played a role that he himself had pushed for the completion of the orchestral variations: Schoenberg had been working on the composition since 1926, and had experienced difficulties with the 5th variation. Several times he tried to find the original structural concept again.

It was Furtwängler’s question as to how far the new work had progressed that motivated him to continue, and he replied to the conductor in May 1928 that the variations were three quarters finished and would “certainly take no more than 14 days to complete”. In fact, he was not able to complete the score until mid-September.

An unbelievable hullabaloo

And that was when the catastrophe began. In his 1965 memoir, Gregor Piatigorsky, who had been principal cellist of the Berliner Philharmoniker since 1924, recalled an almost unbelievable hullabaloo during the rehearsals for the premiere of this incredibly demanding work: there was far too little time, Furtwängler went through the score bar by bar, but no one understood anything. Why didn't F-sharp major sound like F-sharp major? Why did the semiquavers look so strange? How do you perform pizzicato and bow at the same time? The next day Furtwängler appeared with the bad news: they only had one more rehearsal; and the composer would be at the concert! Now disaster loomed, and no one knew what to do. But then, at noon, partial salvation: “Gentlemen,” Furtwängler announced with relief, “I have just received the most wonderful news from Vienna: the composer is not coming.” Huge cheers, and bravos. They might not be able to save the piece, but they could salvage their self-respect. In fact, one critic praised “Furtwängler and the Philharmoniker, who in overcoming the almost grotesque difficulties of this score once again demonstrated their supreme skill”. Anton Webern, who was present in the hall, heard it differently and cabled his master to Vienna: “Unbelievable! Utterly irresponsible!”

The press was unanimously negative about the work itself. “Soulless musical arithmetic”, “grotesque constructs of atonalism”, and an “incurable stubbornness” on the part of the composer, were the tenor of the journalistic attacks. Most of the audience reacted with icy disapproval, a minority hissed and whistled for all they were worth. An even smaller minority – Schoenberg’s students – wanted to forcibly bring about success through frenetic applause.

Furtwängler capitulated unconditionally. He conducted Schoenberg only once after that: the premiere of his orchestral version of Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in E-flat Major in November 1929. But in 1933 he protested, unsuccessfully of course, against the withdrawal of his professorship in Berlin and continued to stand up for Schoenberg later. He saw in the “efforts of an Alban Berg, Schoenberg et al.” the counterpart to the “modern infantilism of a Shostakovich”, and was always at pains to defend the inventor of twelve-tone music against his narrow-minded followers. Music historians have hardly registered Furtwängler’s commitment to Schoenberg and several other contemporary composers. They had other things to do: while Schoenberg’s nationalist outbursts were hushed up or played down, Furtwängler had to be defamed as the general music director of the devil. And in his last years, Furtwängler also had to endure the fact that he, who had written the greatest German symphony of the entire century with his Second Symphony in E minor, was not to be taken seriously as a composer.

Arnold Schönberg in exile

In the 1940s, composers, writers, visual artists and other intellectuals who had fled the Nazis gathered in Los Angeles.

Schoenberg’s Slap-in-the-Face Concert

A memorable Schoenberg performance in 1913

March of an asthmatic

The genesis of Alban Berg’s Three Pieces for Orchestra