Although only its first two movements were played in Berlin in June 1923, this partial premiere of Berg’s Three Pieces for Orchestra op. 6 proved surprisingly successful, laying the foundations for the Viennese genius’s international reputation.

It should never have worked. If things had taken their normal course, Berg would never have been allowed to write this piece; his teacher, Arnold Schoenberg, whom he worshipped like a god, was against the idea. Even later, Schoenberg never so much as mentioned the work. Berg had originally intended to write a single-movement symphony, but he decided instead on an orchestral piece in three movements, a change of genre that entailed far-reaching changes in its underlying conception. Moreover, the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 meant that what had been intended as a carefree work acquired a radically different character. Finally – and after a lengthy period of time – came the welcome threat of a world premiere, placing the composer under extreme pressure, since there was neither a printed edition nor a piano reduction of the score. And there was only limited rehearsal time, which, in light of the work’s great difficulty, left all the participants fearing the worst.

A nagging teacher

The problems of 1923 were not new. Rather, the events of that summer marked the culmination of a crisis that had begun ten years earlier. And problems with tradition are notoriously hard to solve. Berg and Schoenberg had spent a few days together in Berlin in the summer of 1913. Although Schoenberg was no longer Berg’s teacher, he continued to criticize his young colleague, nagging him about his lack of ambition and his weak resolve, to say nothing of his indecipherable handwriting and sloppy dress.

Berg took these reproaches to heart, reacting particularly badly to Schoenberg’s criticism of his compositional style, a style that he himself now described as insignificant to the point of worthlessness. Schoenberg was strikingly unenthusiastic about performing his former pupil’s Altenberg Songs and Clarinet Pieces. Indeed, it seemed positively mean-spirited in comparison to the help that Berg had offered him over a period of many years. Commentators have drawn a comparison between Berg’s self-destructive willingness to sacrifice himself to his mentor’s demands and the self-effacing conduct of Wozzeck and Countess Geschwitz, characters in Berg’s operas. Indeed, many of Berg’s works were inspired by personal experience, a feature that won few friends among his contemporaries, who preferred abstract objectivity.

A tormentingly protracted compositional process

The situation threatened to get out of hand in 1913, when Berg decided to write a symphony – the very medium that is the hardest to reconcile with the tenets of dodecaphony. Symphonies draw their strength from the idea of conflict, be it thematic, harmonic or rhythmic: they report wordlessly on an event that listeners can follow by distinguishing between individual segments and recognising them again in the course of the piece.

The twelve-note method of composition provides only a rudimentary basis for such an approach. Normally when we listen to a symphony, we remember certain details, and it is these that provide us with a sense of orientation, but in the case of dodecaphonic works these points of reference are far more difficult for the listener to identify. Berg’s attempt to meet Schoenberg’s rigorous demands without abandoning his own personal language, with its affinities to Mahler’s musical idiolect, resulted in a compositional process that lasted many years and occasionally proved a source of torment.

The outbreak of the First World War only made things worse. In 1915, before he was conscripted, Berg completed work on the second movement, Round Dance, in western Styria, not far from the Italian front. By now the work as a whole had acquired a title: Three Pieces for Orchestra. Berg had abandoned not only the title “symphony” but also much of the material that he had already written. Schoenberg had wanted the Round Dance to be designed along carefree lines, but by 1915 there could no longer be any question of such an approach. Berg’s depression in the face of the war as well as his health problems both left their marks on the score. In a letter to Schoenberg he described the oppressive-sounding final movement as “the march of an asthmatic, which is what I am and, it seems, what I shall always be”.

»Upbeat«: An introduction with Kirill Petrenko

Belated premiere

We do not know exactly when all three pieces – Prelude, Round Dance and March – were finished, although their dedicatee, Schoenberg, had received all three of them by August 1915. Erwin Schulhoff wanted to perform them in Dresden in the summer of 1919, but the plan fell through, and it was not until 1923 – presumably at the instigation of Hermann Scherchen – that a partial premiere was arranged at that year’s Austrian Music Week Festival in Berlin. On 2 and 3 June the Berliner Philharmoniker gave two performances of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony under the direction of Paul Pella, and on 24 June Alexander Zemlinsky conducted his own Maeterlinck Lieder, after which Anton von Webern conducted his Passacaglia and the first two of Berg’s Three Pieces for Orchestra op. 6. Pella was a young conductor from Vienna who organized and financed the festival, additionally paying for Berg’s trip to Berlin.

For the concert in the Philharmonie, the orchestral parts that Berg had had copied four years earlier for the projected performance in Dresden had to be obtained at short notice. Unfortunately only two rehearsals were possible, hence the absence of the March. Despite this, composer and conductor were able to fire off enthusiastic reports to Vienna. Berg stressed “that everything is very easy to perform – more especially when the orchestra is as fabulous as this one. Even the most difficult phrases were played with pure intonation, and all the notes were absolutely right, something I would never have thought possible”. For his part, Webern noted: “There was negligible dissent. The orchestra played magnificently.”

The audience’s response was astonishingly positive, and not even Berlin’s critics sharpened their knives, as they generally – and gleefully – did with modern programmes. A good two years later the knives were back out when Wozzeck was premiered at the Berlin State Opera. Most of what the critics wrote can now be dismissed as pre-Fascist scribblings, with few authors taking the trouble to judge Berg’s music with any real seriousness.

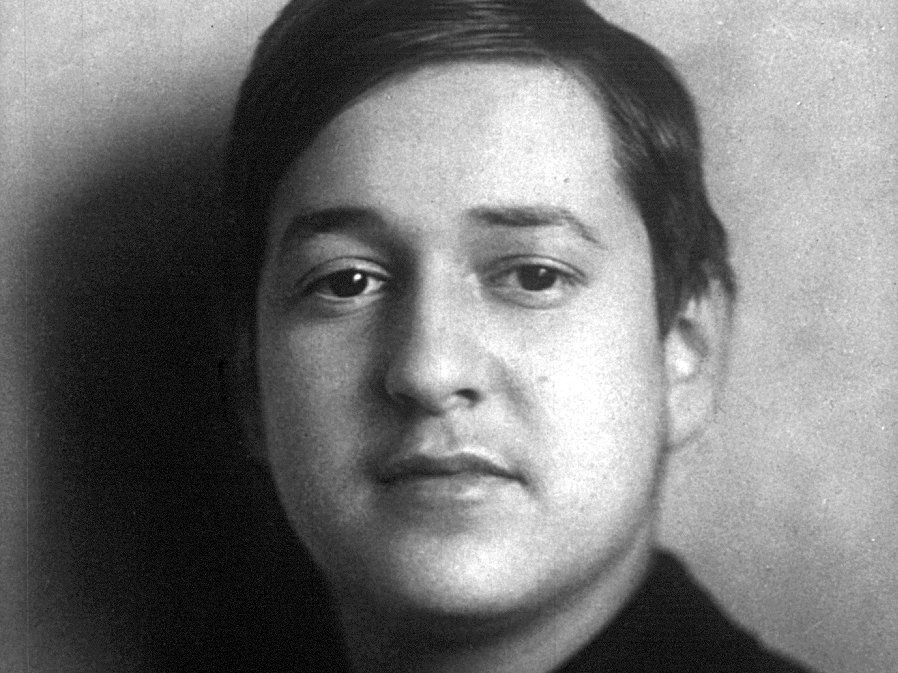

Only rarely did he meet with their approval, and only once was he roundly praised by the press, although on this occasion it was not for his music. Ten days after Wozzeck had opened, the Berliner Morgenpost reported that the composer had had the presence of mind to rescue a man who had fallen on to the tracks at the Friedrichstadt underground station, saving him from the fast-approaching train. Although suffering badly from asthma, Berg still had the strength to do this. Ten years later, however, his body was already too weak to ward off the effects of an insect bite. Alban Berg died from blood poisoning in 1935.

Arnold Schönberg in exile

In the 1940s, composers, writers, visual artists and other intellectuals who had fled the Nazis gathered in Los Angeles.

Schoenberg’s Slap-in-the-Face Concert

A memorable Schoenberg performance in 1913

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

In the 1920s, Korngold was one of the most frequently performed opera composers of the time.