Concert information

Info

Brothers Lucas and Arthur Jussen bring refreshing modernity to the piano duo genre, with their relaxed presence and the close synchronicity of their playing. They make their debut with the Berliner Philharmoniker with a work which brought another sibling duo great success: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed his brilliant Concerto for Two Pianos for himself and his sister Nannerl. Additionally, Michael Sanderling conducts Johannes Brahms’ First Piano Quartet in Arnold Schönberg’s lush arrangement. Discover why the Hungarian folk music references of the final movement caused such a stir when the quartet was first performed.

Artists

Berliner Philharmoniker

Michael Sanderling conductor

Lucas & Arthur Jussen piano duo

Programme

Franz Liszt

2 Episodes from Lenau's Faust: No. 2 Der Tanz in der Dorfschenke (1st Mephisto Waltz)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Concerto for two Pianos and Orchestra in E flat major, K. 365

Lucas & Arthur Jussen piano duo

Interval

Johannes Brahms

Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, op. 25 (orchestrated by Arnold Schoenberg)

Additional information

Duration ca. 2 hours and 15 minutes (incl. 20 minutes interval)

Main Auditorium

39 to 111 €

Introduction

19:15

Series K: Concerts with the Berliner Philharmoniker

Main Auditorium

39 to 111 €

Introduction

19:15

Series I: Concerts with the Berliner Philharmoniker

Main Auditorium

39 to 111 €

Introduction

18:15

Series N: Concerts with the Berliner Philharmoniker

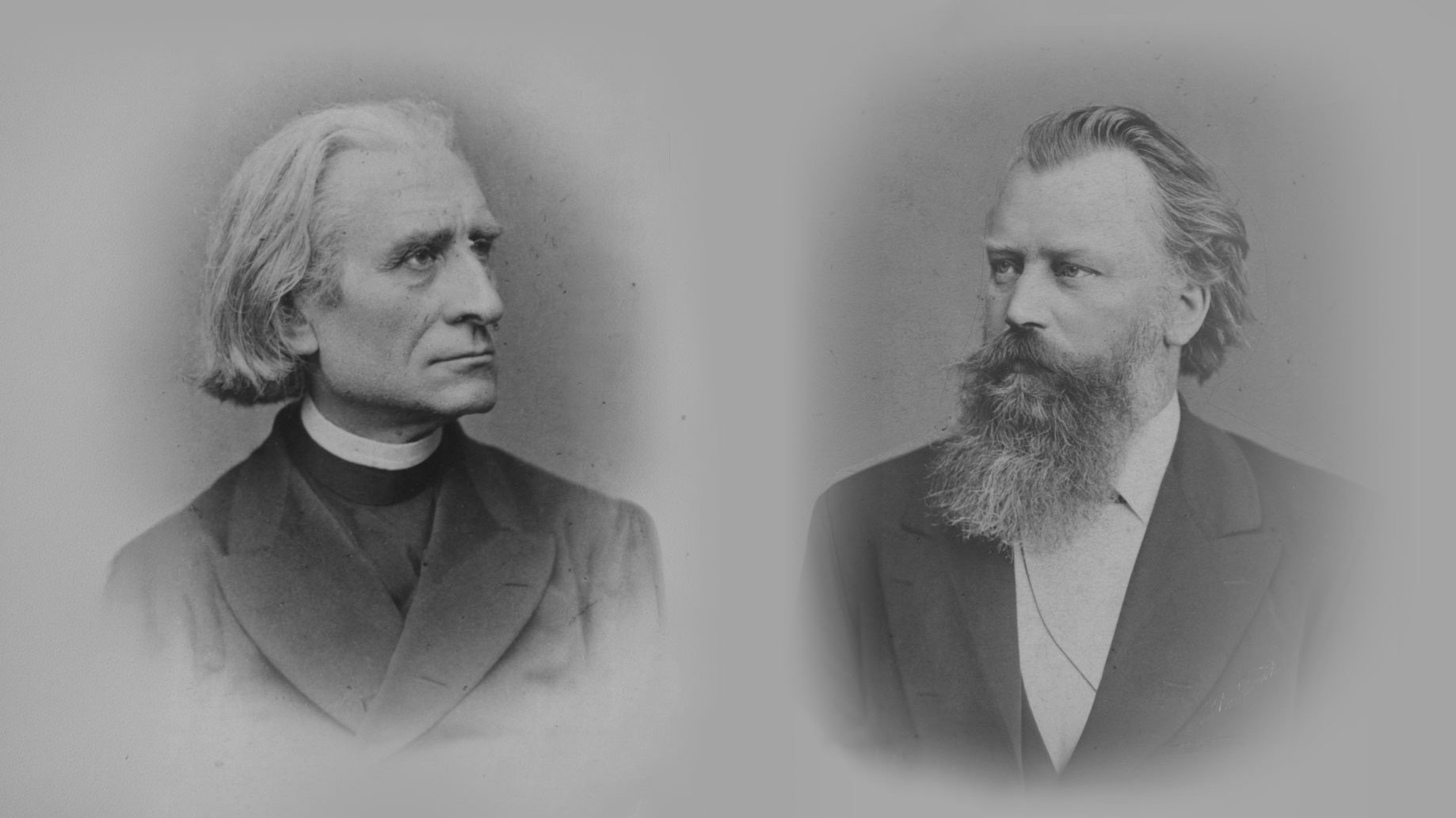

Brahms versus Liszt

The musical conflict of factions

In the second half of the nineteenth century, a fundamental question divided the musical world into two irreconcilable camps: should the music of the future build upon the achievements of tradition – or break radically with everything handed down through the ages? Each side had its prominent champions …

“Children! Make something new! New things, and yet more new things!” demanded Richard Wagner in 1852 in a letter to Franz Liszt. “If you cling to the old, the devil of unproductivity has got you, and you will be the saddest of artists!” Johannes Brahms saw matters quite differently: he looked to the masters of the past, to Bach and Haydn, and even called the music of his own time a “cesspool”. By the end of the 1850s, this conflict had escalated into what became known as the War of the Romantics. On one side stood the “New German School” surrounding Wagner and Liszt, on the other, the “Conservatives”, with Brahms and the violinist Joseph Joachim as their leading figures.

Brahms felt a pronounced aversion to the works of Franz Liszt. As early as 1853, when he paid Liszt his respects in Weimar and the latter played his latest creations at the piano, Brahms is said to have fallen asleep during the performance of the Sonata in B minor. In letters, he would later brand Liszt’s compositions as “rubbish”, even as a “plague” that was corrupting the taste of the public. “I am often itching to start a quarrel, to write Anti-Liszts,” Brahms confessed to Joseph Joachim in the summer.

In 1860, this impetus led to a laboriously-formulated declaration against “the activity of a certain faction”, whose products, he claimed, were “contrary to the very essence of music”. Liszt, who dreamed of ushering in a new age of art, had little need to respond personally. The journalist Franz Brendel took over for him, penning scathing polemics in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. This led to Brahms being ridiculed as “Hans Neubahn” – a cruel jibe at the enthusiastic article his mentor Robert Schumann had once written about him, entitled New Paths. After this humiliation, Brahms responded only with his music. But he had to live with the damage – and with the reputation of being an incorrigible conservative.

Biography

Michael Sanderling

One of the few orchestral musicians who have successfully made the switch to conducting, Michael Sanderling comes from a family of musicians. He became principal cellist of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra at the age of 20, before spending many years in the same role with the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin. In parallel, he pursued a solo career, performing with orchestras such as the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. In 2000, he made his conducting debut with the Kammerorchester Berlin—marking the start of his second career: “I believe it is generally a great advantage if, as a conductor, you can assess what is happening on stage, also from the perspective of an orchestral musician,” says Michael Sanderling, who made his first appearance with the Berliner Philharmoniker in May 2019.

Since 2021, he has been chief conductor of the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra. Prior to that, he was chief conductor of the Kammerakademie Potsdam and the Dresden Philharmonic, developing the latter into one of Germany’s leading orchestras. For his role in the Cologne Opera's new production of Sergei Prokofiev’s opera War and Peace, he was named “Conductor of the Year” by Opernwelt magazine in 2011. As a guest conductor, Michael Sanderling regularly performs with major international orchestras, including the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Lucas & Arthur Jussen

Whether Lucas and Arthur Jussen sit at two grand pianos or share the keyboard of a single instrument, according to Berlin newspaper Der Tagesspiegel, “it is always palpable to the audience how close the two brothers are. They play with a shared breath, their energies flow together symbiotically, only to erupt in gripping interpretations”. Their playing, observes the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, seems effortless and completely natural. By now, the charismatic brothers—who were born three years apart in Hilversum—have reached the top tier of the international classical scene, with guest appearances at leading ensembles such as the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Berliner Philharmoniker, with whom they are making their debut in these concerts.

Only during their years of study were they separated for a longer period: Lucas completed his training with Menahem Pressler in the USA and Dmitri Bashkirov in Madrid, while Arthur studied at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam with Jan Wijn. Of course, even during this time, they regularly came together for joint performances, constantly swapping roles: sometimes one plays the upper octaves, which usually contain the melodic lines, sometimes the other. “Before every new piece we work on, we flip a coin,” says Arthur Jussen.

Plan your visit

Opening hours, program booklets, dress code, introductions and more

How to get to the Philharmonie Berlin

Whether by bus, train, bike or car: Here you will find the quickest way to the Philharmonie Berlin - and where you can park there.

Ticket information

Advance booking dates, opening hours, seating plans, discounts