- Orchestra History

- History

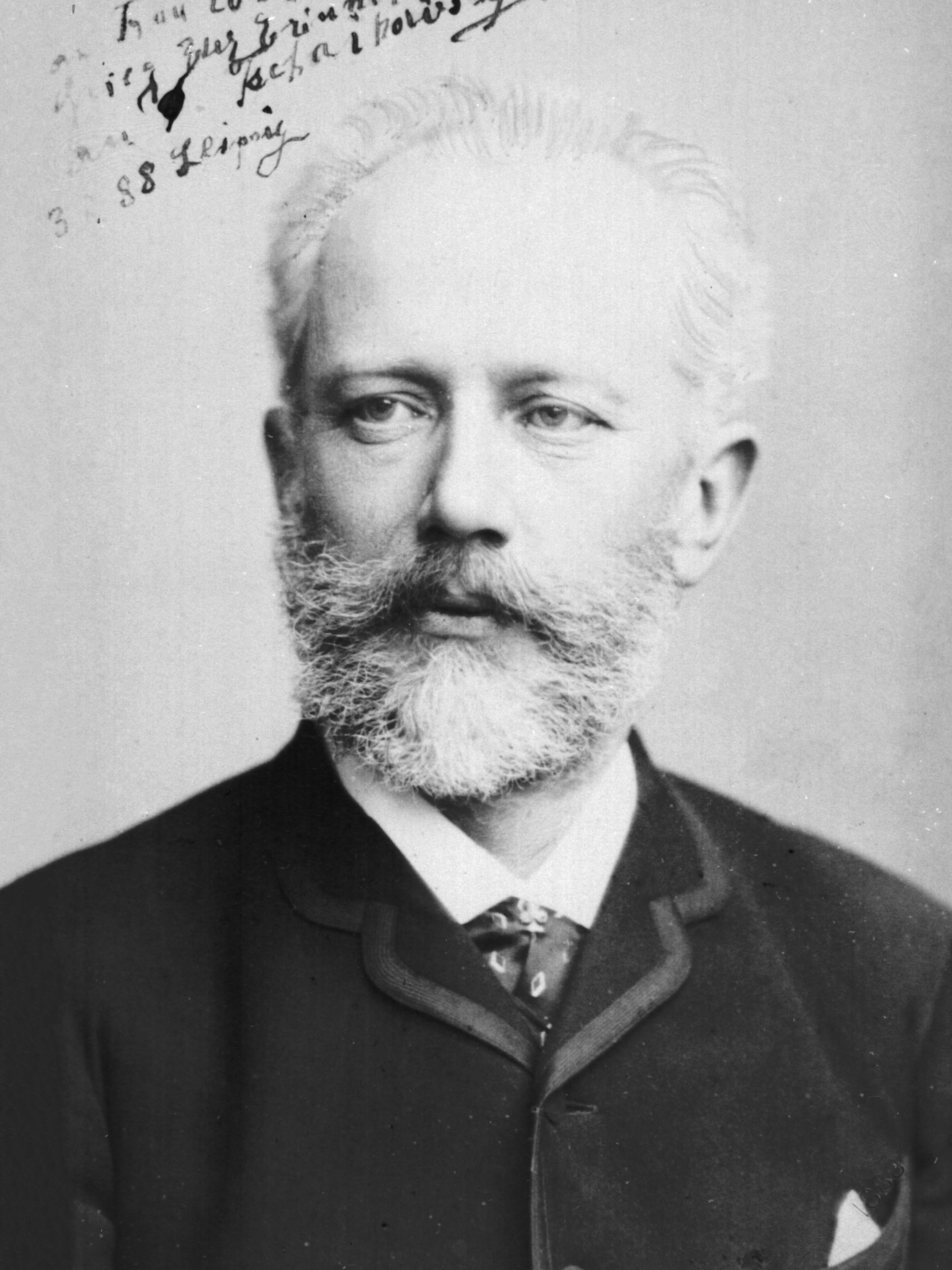

Twice during his European tours, Pyotr Tchaikovsky conducted the Berliner Philharmoniker – in February 1888 and again in 1889. In between, during the summer of 1888, he composed his Fifth Symphony. The collaboration between the composer and the orchestra had a longer and somewhat delicate prelude ...

Art is sometimes a step ahead of politics. On 8 February 1888, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky stood on the podium in front of the Berliner Philharmoniker to conduct his own works. This, his first public concert appearance in the German capital, was a major event.

The critic of the Neue Musikzeitung rejoiced: “Now, at last, he has seen fit to revive the German-Russian friendship, which had fallen into serious disarray, by appearing in person on the neutral ground of art. That he succeeded to some degree is beyond question...” The political relationship between Germany and the Tsarist Empire was difficult at the time, but Tchaikovsky and his music conquered Europe.

A tenacious orchestral chairman

The Berlin audience owed Tchaikovsky's presence to the initiative of Otto Schneider, horn-player and chairman of the Philharmoniker. He had read in a music journal that the composer was planning a European tour, and invited him to Berlin for a concert with his orchestra. Tchaikovsky immediately accepted, but there were some problems in the run-up to the concert.

To organise his tour, the composer had hired the concert agent Dmitri Friedrich, who would have preferred to have had him perform at the Concerthaus on Leipziger Strasse. The orchestra there was the successor to Bilse's orchestra, from which 50 musicians, including Otto Schneider, had left under less than amicable circumstances to found the Berliner Philharmoniker. While Bilse had filled his decimated ranks with new musicians and continued to perform in the Concerthaus in Leipziger Straße before handing over his orchestra to a successor in 1885, the 50-strong splinter group went on to become the city's leading orchestra in the Philharmonie in Bernburger Straße.

Friedrich's plan was not so far-fetched, as the composer held Bilse's orchestra in high esteem, having already heard it several times during previous stays in Berlin. Moreover, Bilse was very committed to Tchaikovsky’s music; among other things, he had performed Tchaikovsky’s orchestral fantasy Francesca da Rimini for the first time in Berlin in 1878. Otto Schneider became aware of Friedrich’s courtship of the Concerthaus Orchestra.

Under no circumstances was it to be allowed to win the contract! Schneider reacted immediately. He sent a letter to Tchaikovsky, imploring him to perform only with the Berliner Philharmoniker, the “best orchestra in the city”: “You owe that to yourself and to your good artistic name,” he wrote. Tchaikovsky reassured him that he had “resolutely” refused Friedrich and had “decided exclusively upon the Philharmoniker”. He confirmed 8 February 1888 as the concert date, and also sent along a programme proposal: to open either with the Romeo and Juliet Overture-Fantasy or Francesca da Rimini.

Friendly reception

In early January 1888, he met in Berlin with Otto Schneider, a “very agreeable, friendly gentleman”, according to his description, to discuss the more precise modalities of the planned concert. The preparation of the programme was – as Tchaikovsky reported – “fraught with not inconsiderable difficulties”. Tchaikovsky definitely wanted to present Francesca da Rimini, but Schneider advised against it. “He considered it risky to play such a complicated piece, which in his opinion would be difficult for the audience to like, for my first appearance in Berlin,” Tchaikovsky recalled in his account of the trip.

Tchaikovsky was thoroughly impressed by the orchestra: “The Berliner Philharmoniker, alongside all its other merits, possesses a particular quality for which I can find no more fitting word than elasticity. By that I mean the ability to adapt to the scale of Berlioz or Liszt – to master the complex, multilayered orchestral textures of Berlioz as perfectly as the thundering percussion of Liszt – while also fully adjusting to the musical style of Haydn. It is easy to see why: while the Gewandhaus Orchestra focuses almost exclusively on classical repertoire, and the Liszt Association mainly performs modern works, Berlin – much like St Petersburg and Moscow – offers concerts where Haydn appears alongside Glazunov, Beethoven alongside Bizet, Glinka alongside Brahms, and everything is performed with the same love, the same enthusiasm, and the same high quality of ensemble playing.” He further wrote in his Autobiographical Account of a Journey Abroad in 1888: “The members of the Berliner Philharmoniker are not required to perform in theatres, and are therefore neither overworked nor weary, and because they are a self-governed organisation, they perform for their own benefit and not in the service of an impresario who pockets the lion’s share of the profits. Naturally, the convergence of these favourable conditions has a very positive effect on the quality of the artistic performances. Already at the first rehearsal I was encouraged by the kind attentiveness and enthusiasm of the orchestra members, and everything went smoothly and satisfactorily from the very beginning.”

Schneider knew what he was talking about, having played in the performance of the work in 1878 as a member of Bilse’s Kapelle and having experienced the audience’s chilly response. His opinion was shared by Hans von Bülow, then chief conductor of the Berliner Philharmoniker, and Hermann Wolff, the orchestra’s concert agent. Tchaikovsky bowed to the decision of the three, dispensed with Francesca and conducted Romeo and Juliet instead.

Berlin audiences finally had the opportunity to hear Francesca da Rimini under Tchaikovsky's baton the following year during the composer’s second major European tour. “The hall was full to overflowing,” the composer wrote to his brother Modest. “The success – a great one, although Francesca did not actually have the effect I was expecting: the orchestra played so wonderfully that it seemed to me that the audience was in raptures for that alone. I heard two or three whistles very clearly.” Tchaikovsky’s report is also consistent with the press reactions.

The critic of the Vossische Zeitung wrote: “We already knew the symphonic poem from Bilse’s concerts. This time, too, its impression on us was not a favourable one. In part, it repels us with its violence of expression and sound imagery, in part it tires us with the endless repetition of insignificant motifs.” Tchaikovsky’s account aligns with the reactions in the press, which received the work with significant reservations. The composer accepted the verdict calmly. Two days after the concert in Berlin, he travelled on to Leipzig, continuing his successful European tour.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Ballet

Tchaikovsky is rightly considered the maestro of ballet music. He defended it against contemporaries who classified it as mere incidental music. A love story.

Modest Tchaikovsky: brother and librettist

It is a very rare occurrence for siblings to write an opera together. With Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and his brother and librettist Modest, the collaboration was a success in the case of “Iolanta” and “The Queen of Spades”.

The remarkable friendship of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck

The remarkable friendship of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck