- History

They felt like soul mates – and yet never met in person: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and the rich widow Nadezhda von Meck. Their correspondence, which lasted over 20 years, is probably one of the most unusual relationships in the history of music and at the same time an exciting source of information for Tchaikovsky’s biography.

“Before I met you,” Tchaikovsky wrote to Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck in November 1877 from the Swiss spa town of Clarens on Lake Geneva, “I did not know that there were people with such an affectionate and deep disposition. Not only what you do for me borders on the wonderful. Your letter expresses so much warmth and friendship that I love life again and am determined to withstand all adversity. It is thanks to you that my love for work has returned with redoubled strength. Never, ever, not for a moment will I forget that you have helped me to continue to pursue my artistic profession [...]. I am gradually beginning to work again, and I will finish our symphony [the Fourth] in December at the latest”.

Emerging from a serious life crisis

This letter was preceded by one of the composer’s most serious life crises, which began with his hasty marriage to the young student Antonina Ivanovna Miliukova. Tchaikovsky had married her in July 1877 in order to satisfy social conventions – a “mad enterprise”, according to his brother Modest Tchaikovsky, which had disastrous consequences: after a failed suicide attempt in early September, the hypersensitive composer suffered a physical and psychological breakdown that left him unconscious for almost 48 hours.

He then instructed his brother to arrange a divorce and travelled to Switzerland, Paris, Florence, Rome, Venice and Vienna to recuperate. During this time, he wrote two of his most important works: Eugene Onegin and the Fourth Symphony, the score of which was completed in early January 1878. The opera, based on the Pushkin novel of the same name, was to be something of a reflection of the composer’s disappointments and distress.

To “my best friend”

The Fourth Symphony, whose moderately successful Moscow premiere on 22 February 1878 was conducted by Nikolai Rubinstein, represented the overcoming of the crisis – it is no coincidence that it is dedicated to “my best friend”. This referred to Nadezhda von Meck, who had entered the life of the then 37-year-old composer immediately after the “embarrassing catastrophe of the short marriage” (Tchaikovsky) – mediated by the violinist Josef Kotek, who was employed as a music teacher and chamber music partner in her house and shared and inspired her passion for Tchaikovsky's music.

In order to tactfully support the composer, who was constantly in financial difficulties, Nadezhda Filaretovna had commissioned some piano pieces for an unusually high fee, for which she thanked him in December 1876: “It is superfluous to tell you how delighted I am with your composition, since you are probably used to praise from other quarters. So I will only say [...] that life is easier and more pleasant with your music.”

This was the first of a total of 1204 letters that the two wrote to each other without ever meeting in person – a remarkable occurrence that finds no parallel in other artists’ biographies. For both of them, the correspondence was obviously of great importance. It provides valuable information on Tchaikovsky’s biography, who describes his travels in detail in the letters, but also comments on his creative work in addition to his aesthetic and artistic convictions and philosophical-religious views.

A consummate and accomplished music lover

In Nadezhda von Meck, he found a consummate and accomplished music lover – and a person of extraordinary empathy, which the reclusive composer apparently did not want to jeopardise by meeting in person:

“The most beautiful moments of my life are those in which I see my music capture the hearts of those I love and whose involvement is more valuable to me than fame and success with the public. I don’t need to tell you that you are the person I love with all my heart. For I have never met anyone like you, whose soul would have been so familiar to me, who would have responded so sensitively to my every thought, to every beat of my heart. Your friendship is as indispensable to me now as the air I breathe, and there is not a moment in my life when I am not thinking of you”.

Tchaikovsky’s music, in turn, could put Nadezhda von Meck into a “state of intoxication like a glass of sherry”, while the “infinite melancholy” of some pieces sometimes also took her “breath away”.

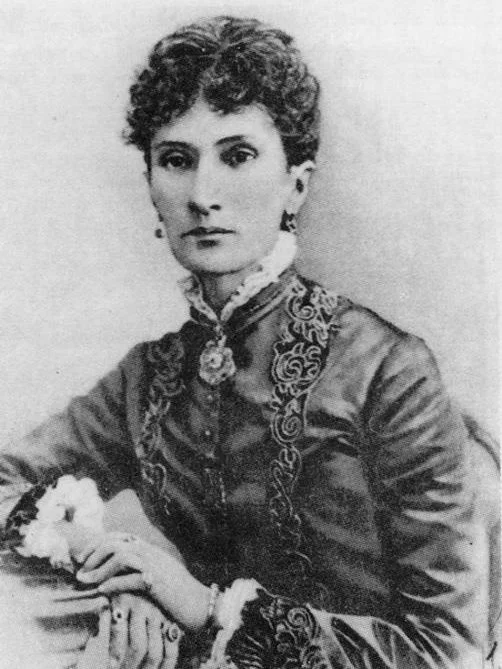

At the age of 17 she married Karl von Meck, who in 1860 exchanged a modest job as a civil servant for that of an independent entrepreneur and made a fortune by building railway lines – not least thanks to the energy of his enterprising wife.

When he died on 7 February 1876, Nadezhda Filaretovna was 45 years old and the mother of eleven children. She owned two railway networks, a magnificent house in Moscow, an idyllic estate in Brailiv, Ukraine, and a fortune of several million roubles. Music was and remained her great passion, and so in around 1880 she supported the violinist and composer Henryk Wieniawski, who had fallen seriously ill on a tour, and took him into her home.

Brief employment of Debussy

In the same year, the young Claude Debussy was employed as a teacher and piano partner by the wealthy widow, but was immediately released from his services when he asked for the hand of her fifteen-year-old daughter Sonja. Nevertheless, at the centre of Nadezhda von Meck’s intense passion for music was the work of Tchaikovsky, who she initially provided with further highly remunerated commissions before paying him an annual pension of 6,000 roubles.

Abrupt end of the relationship

Why she ended their correspondence without explanation in September 1890 and also stopped her payments is not known. As early as the 1880s, the tone of both had become increasingly businesslike, and the intervals between letters had also increased, which was not least due to the failing health of von Meck, who was suffering from tuberculosis. It is possible that her decision was influenced by the fact that Tchaikovsky received an annual pension of 3000 roubles from Tsar Alexander III from 1888.

Also, the patron’s weakened health may have meant that she could no longer exercise control over her affairs alone and was forced to comply with her relatives’ demands to end her support. The seriously ill Nadezhda von Meck survives him by only three months – according to her daughter-in-law Anna von Meck, she had been unable to come to terms with Tchaikovsky’s death.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Ballet

Tchaikovsky is rightly considered the maestro of ballet music. He defended it against contemporaries who classified it as mere incidental music. A love story.

Modest Tchaikovsky: brother and librettist

It is a very rare occurrence for siblings to write an opera together. With Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and his brother and librettist Modest, the collaboration was a success in the case of “Iolanta” and “The Queen of Spades”.

Gustav and Alma Mahler

Should she really accept his offer of marriage? At twenty-two, Alma was an extraordinarily beautiful and charismatic woman. Mahler was a social climber from the provinces.