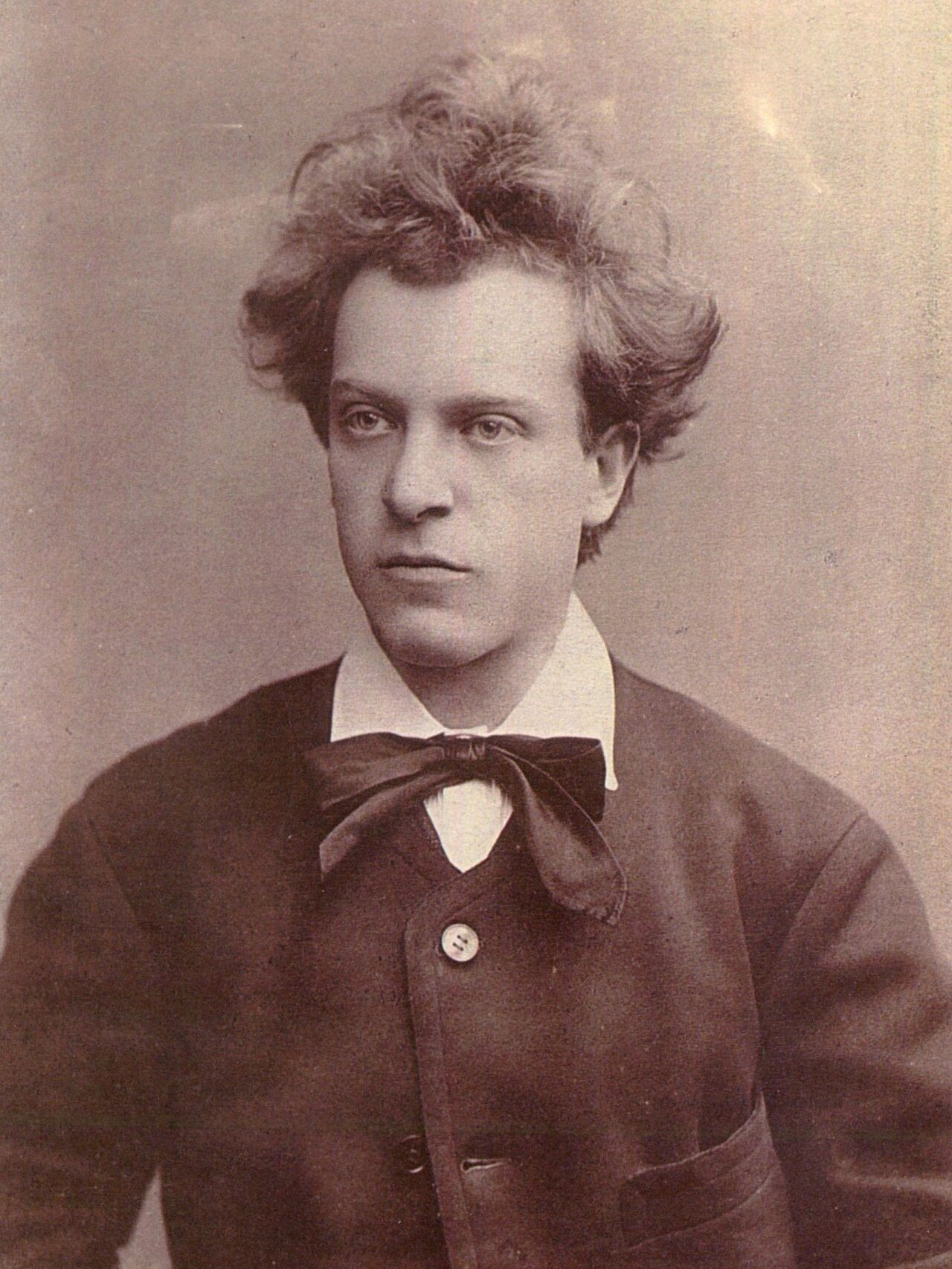

- Portrait

“That sounds just like Mahler!” This is a common response to hearing Hans Rott’s E major Symphony for the first time. This visionary work had to wait 110 years for its first performance, but it has finally found its place in the mainstream concert repertoire.

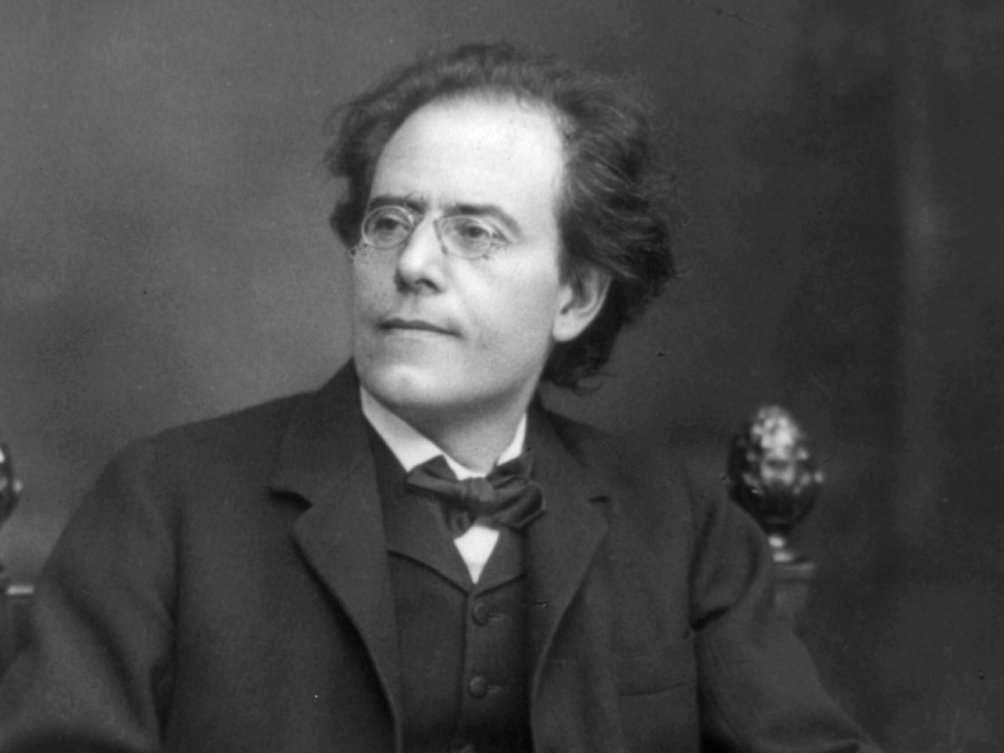

For over a century his name was completely forgotten, his works less than a distant memory. If experts had been asked even forty years ago who Hans Rott was, their response would almost certainly have been to shrug. Some might have recalled that Mahler once told his close friend and confidante Natalie Bauer-Lechner about a fellow composer who had been an early friend of his but who had died young: “What music has lost in him is immeasurable. His First Symphony, written when he was a young man of twenty, already soars to such heights of genius that it makes him – without exaggeration – the founder of the New Symphony as I understand it. […] His innermost nature is so akin to mine that he and I are like two fruits from the same tree, produced by the same soil, nourished by the same air.”

Despite Mahler’s euphoric assessment of his colleague’s work, his growing band of admirers took remarkably little interest in Rott. It was not until 1989 that the E major Symphony about which Mahler had spoken so enthusiastically received its world premiere in Cincinnati. It triggered an avalanche; observers began to speak of “Mahler’s Nullte”, an allusion to Bruckner’s early “Symphony No. 0”. Rott’s work was seen as a model and as a precursor of Mahler’s own First Symphony. Performances followed in Paris, London and Vienna, and there are now no fewer than twelve recordings of it in the catalogue, not to mention several books and a whole range of scholarly articles. Almost overnight, Hans Rott has become the gateway to music's modern era.

A student of Bruckner

Rott's legend owes some of its spice to the fact that the composer's short and tragic life ended in an asylum in Lower Austria in 1884. He was born in Vienna in 1858, two years before Mahler. Both of his parents were actors. His love of music was fostered by his parents, and he was encouraged to enrol at the Vienna Conservatory in 1874. His gifts as a musician must have caught the attention of the authorities, because when his family fell on hard times in the wake of his father’s death in 1876, Rott was awarded a scholarship that allowed him to continue with his studies there.

Like Mahler, Rott attended Franz Krenn’s composition class, and both men took organ lessons from Bruckner, who in 1877 wrote an excellent letter of recommendation: “Hans Rott […] is a brilliant musician, extremely kind and modest, of excellent character, plays Bach outstandingly well and, although only eighteen, is astonishingly good at improvisation.” Bruckner’s testimonial ended with the words: “Until now he has been my very best pupil.”

Rejected by Brahms

Unfortunately Bruckner’s “best pupil” did not get on equally well with the most influential of Vienna’s musical figures. In 1878, in order to complete his studies, Rott entered a competition that was limited to the Conservatory’s composition students, submitting the opening movement of his E major Symphony. Six of the seven entrants, who included Mahler, were awarded prizes. Only Rott was left empty-handed. The members of the jury all held strictly entrenched views, and complained that Rott’s submission was too Wagnerian, greeting the performance with mockery and laughter. But Rott refused to be disheartened. He continued to work on his large-scale symphony, completing the score during the late summer of 1880.

Rott decided to enter the completed work in another competition, the prize of which was a state scholarship. This time he adopted a different tactic, calling on the jurors in person and trying to convince them of the validity of his artistic vision. In the middle of September 1880, he invited Brahms to pass judgement on the piece. Brahms’s reaction could hardly have been more devastating. Although there were some beautiful things in it, said Brahms, the symphony contained “so much that is trivial and senseless” that Rott could not possibly have written it all himself. Brahms advised the young composer to find a different profession.

Mental illness

For Rott, this verdict seemed like a death sentence. He was now convinced that Brahms would do everything in his power to place obstacles in his path, and ultimately to destroy him. This suspicion became an idée fixe. He heard male voices, and suffered from paranoid hallucinations. At the end of October he used a pistol to threaten a passenger who attempted to light a cigar in his railway compartment. Brahms, Rott informed the flabbergasted passenger, had filled the whole carriage with dynamite, and they would all be blown sky-high if the man insisted on lighting his cigar. Rott was handed over to the train authorities and committed to a clinic in Vienna. Since his condition did not improve, his detention became permanent.

Rott twice tried to take his own life during his remaining three and a half years. On only a handful of days was he sufficiently lucid to return to composition, but asylums at that time were seldom able to cure psychiatric illnesses. In the end Rott refused food and, skeletally thin, he died from tuberculosis on 25 June 1884, not yet twenty-six years old.

Affinities with Mahler

Was this simply because Brahms rejected Rott’s E major Symphony? Did the piece really deserve to be judged so harshly? Admittedly, the score sounds eclectic in places, notably in its unmistakable allusions to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg near the start of the opening movement. But there are also echoes of Bruckner, especially in the treatment of the winds, as well as in the organ-like registration of the orchestra and the almost manic repetition of individual motifs. Most striking of all, of course, are the similarities with Mahler, whose own symphonies contain the same melodic phrases almost verbatim. Both composers also share an affection for more popular musical idioms, such as folksongs and military marches.

Headed “Sehr langsam” (Very slow), the second movement of Rott’s E major Symphony recalls the final movement of Mahler’s Third, while the Scherzo looks forward to Mahler's Fifth. Rott wrote this music before Mahler wrote his symphonies, so the answer to the question of who influenced whom is evident.

This statement does not need to be taken as a criticism. No composer emerges from nowhere; even Mozart and Beethoven drew on earlier models. We can only regret the fact that despite his high opinion of Rott’s music, Mahler did nothing to promote it — as one of the most sought-after conductors of his day, he had every opportunity to do so. Did he want to avoid revealing his secret, or creating the impression that he had used Rott’s Symphony as a mine for his own inspiration? Mahler really did not need to do this, given his standing and his greatness. But Rott would not have had to wait so long to receive justice. Whatever the case, his E major Symphony, for all its heterogeneity, is an original work of astonishing maturity, and deserves to be heard.

Fanning the flames

Today, concerts featuring Bruckner’s symphonies are among the Berliner Philharmoniker’s seasonal highlights, but this was not always the case. On the Bruckner tradition of the Berliner Philharmoniker.

Love at second sight: Gustav Mahler and the Berliner Philharmoniker

Mahler’s music now features so regularly in the programmes of the Berliner Philharmoniker that it is all too easy to forget that this has not always been the case.

Brahms’s long road to the symphony

“I shall never write a symphony,” Brahms once declared. Discover why he did – even if it took him 15 years.