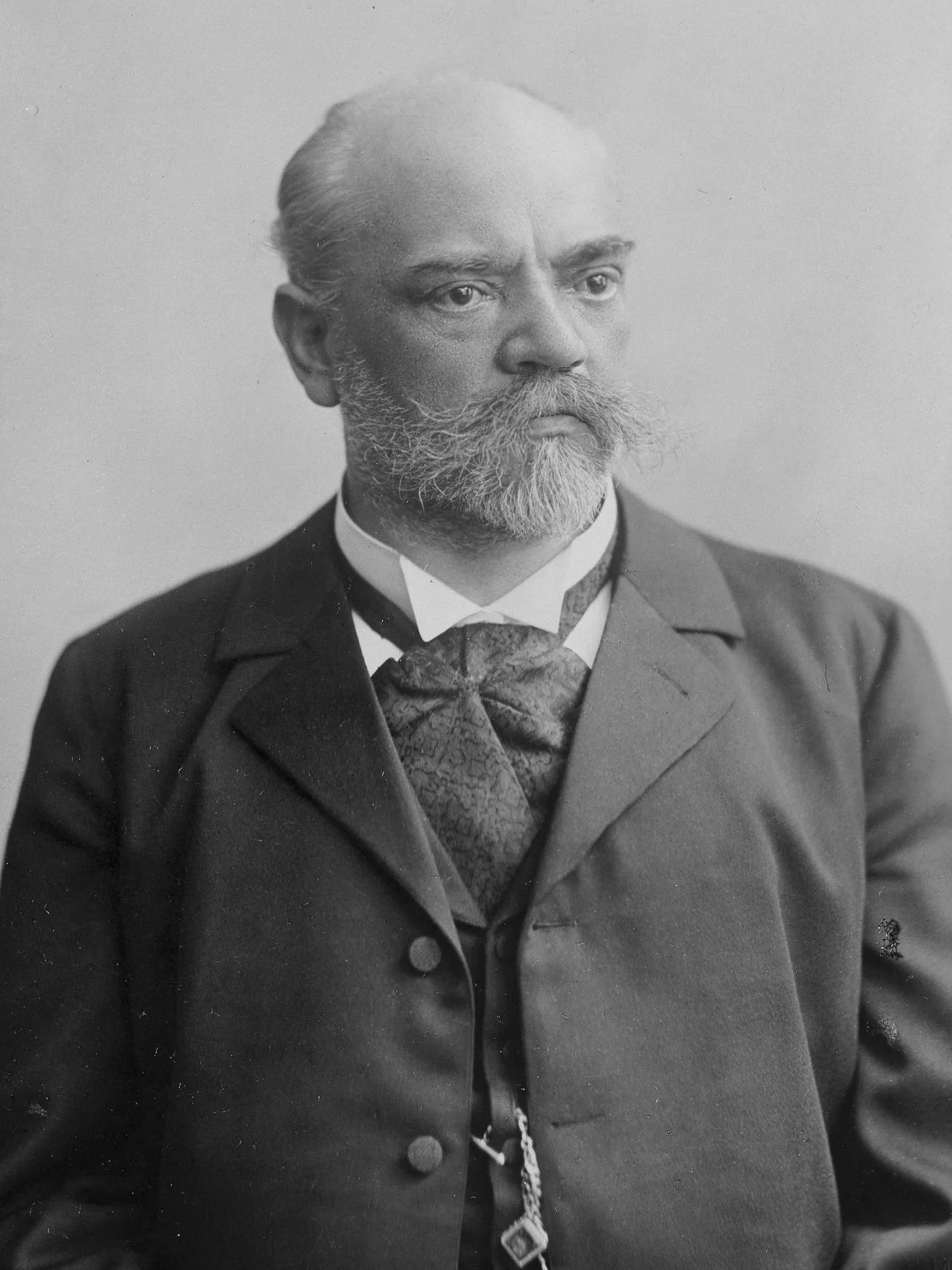

- History

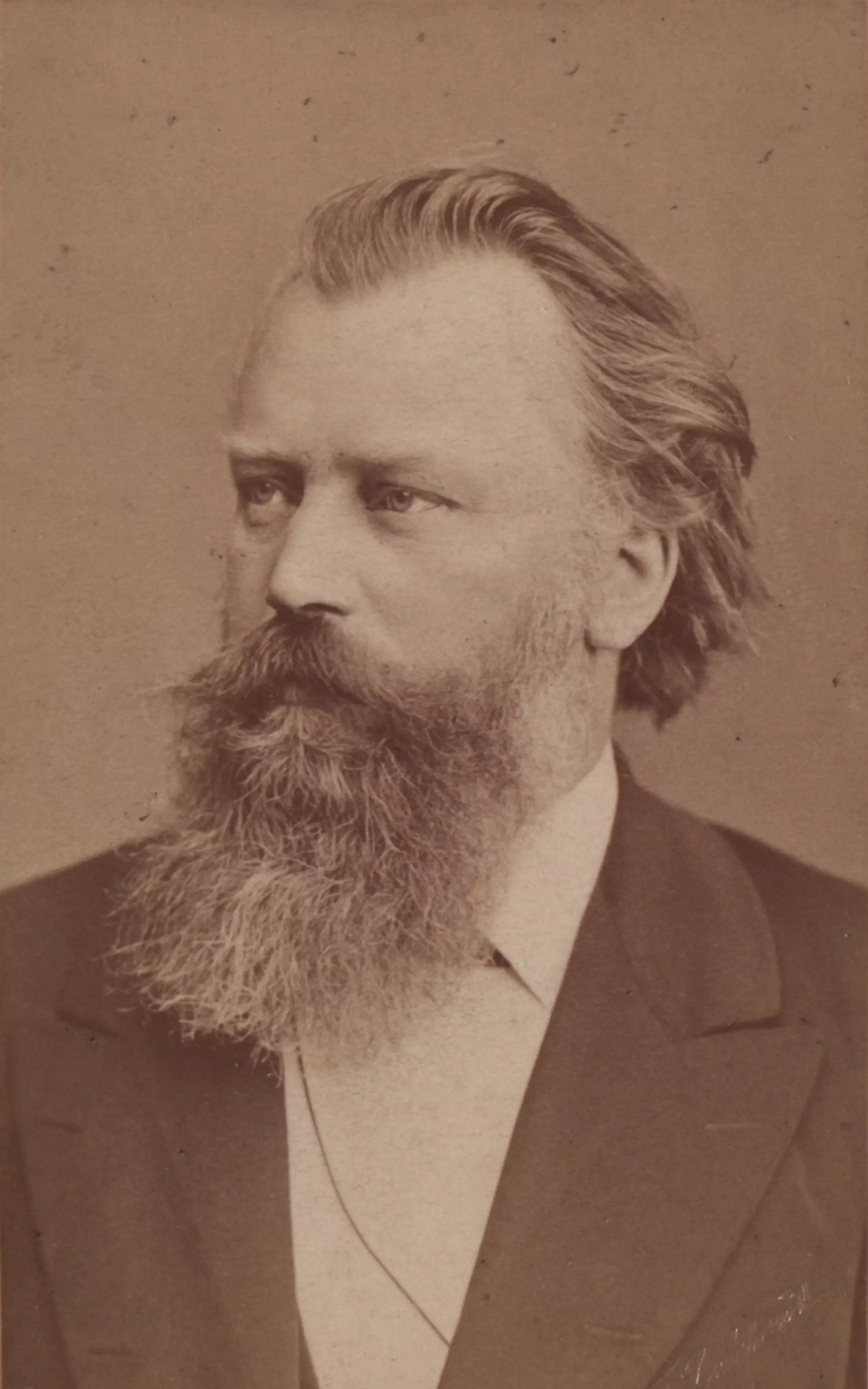

From orchestral musician to national composer – Antonín Dvořák enjoyed an extraordinary career. He owed his success to his musical genius and his unbounded powers of invention, but also to his mentor Johannes Brahms, who recognized the younger man’s unique talent and promoted his music, opening many doors for the Czech composer. It was Brahms who recommended Dvořák’s Stabat Mater to an influential music publisher.

Dvorak’s father, a butcher and innkeeper, played the zither. Dvorak had already begun to play violin when he first encountered an organ in Zlonice, where his parents sent him to study with the local Kantor. The young Antonín Dvořák was becoming increasingly drawn to music. He began composing and continued his education – he had been partly self-taught – at the Prague Organ School. But it was as a violist, rather than as an organist, that he landed his first job in an orchestra.

From 1862, he played at Prague’s new Provisional Theatre (the National Theatre was yet to be built). Dvořák was still in his early 20s when Richard Wagner came to Prague in November 1863 and conducted concert performances of his own works. This was a formative experience for Dvořák, who had the opportunity to play in revolutionary works like the Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin.

Opera projects, chamber music and a first symphony

Dvořák fell increasingly under the spell of this music. Meanwhile, he was composing his own works: he embarked on his first opera projects as well as writing chamber music and, eventually, his First Symphony. But his musical language had not yet reached its full maturity. Many of these works remained on the shelf.

The early 1870s were more successful: for the first time, one of his compositions was performed in public and his song Skřivánek (“The Lark”) appeared in print, soon followed by a string quartet. Dvořák was gaining confidence.

He continued to earn his living primarily from playing the viola, supplementing his income by giving piano lessons. By 1873 he was already at work on his Third Symphony, and the following year he submitted it and other works with an application for an Austrian State Scholarship intended for talented, needy composers in the Habsburg Empire. Among those on the jury were the director of the Imperial Opera in Vienna and the highly influential, Prague-born music critic Eduard Hanslick.

Dvořák was awarded that scholarship as well as further grants in the five subsequent years, when the jury included another composer – Johannes Brahms. He could not as yet have suspected how central a role in his life would be played by Brahms, who strongly advocated behind the scenes on behalf of his young colleague, not only on that jury but later also with his own publisher, Fritz Simrock.

His champion Brahms

Eventually Dvořák discovered who had been promoting his music so assiduously in the background. In December 1877, he wrote Brahms a letter: “Honoured Sir!”, he began. “I venture to address these few lines to you...in order to express to you my deep-felt thanks for the kindness you have shown me.” Dvořák had only just completed his Stabat Mater, a milestone in his artistic development. He submitted a new set of Moravian Duets for soprano and alto to the Vienna jury.

Brahms reacted again with delight and immediately informed his publisher Simrock in Berlin about a volume “that seems to me very pretty and practical for publication”. It would just be necessary to prepare a German translation, because the “texts are only in Czech”. When Dvořák learned of this, he set off at once for Vienna to offer his thanks in person.

He arrived to find that Brahms – who had also recommended the Stabat Mater to Simrock for publication – was away on a concert tour. Dvořák left some compositions he had brought along for Brahms with his landlady.

It would develop into one of the most productive artistic friendships of the 19th century: the ever-modest Dvořák and the critical, occasionally grumbling Brahms. Later they would send each other their new compositions, or play them to one another at the piano. Meanwhile, Simrock was aware of what he had in Dvořák: the goose that lays the golden egg.

A licence to print money

In 1878, Dvořák delivered to Simrock the first eight of his Slavonic Dances, commissioned by the publisher and modelled after Brahms’s Hungarian Dances. For Simrock, as Dvořák wrote, these works represented “a gold mine which cannot be underrated”; these dances were virtually a licence to print money. Dvořák’s fame was growing.

The Seventh Symphony was one of his greatest successes. It was after hearing the Third Symphony of his friend Brahms in 1884 that he decided – following a pause of more than four years – to try his hand again at writing one. The Seventh had its premiere in London in April 1885; it was a new peak in his career.

The flagship years in America followed, including his triumphant premiere with the New York Philharmonic, and the rich, mature fruits of this period, like the “American” String Quartet and the “New World” Symphony. Back in Europe, Dvořák presented a new cello concerto to his friend Brahms, who was thoroughly enchanted by it: “Why didn’t I know that one could write a cello concerto as good as this?” he enthused. “If I had known, I’d have written one a long time ago!” Dvořák composed very little after Brahms died in April 1897, and he followed his friend in death seven years later.

Yearningly successful

His two-and-a-half-year stay in America was an ambivalent time for Antonín Dvořák – characterized by triumphs, enthusiasm about new impressions, but also yearning for his Bohemian homeland.

Between heaven and earth

Johannes Brahms and the Berliner Philharmoniker share a special history. We take a deeper look at his “Song of Destiny”.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Ballet

Tchaikovsky is rightly considered the maestro of ballet music. He defended it against contemporaries who classified it as mere incidental music. A love story.