Richard Strauss’ “Ein Heldenleben” as a travel repertoire

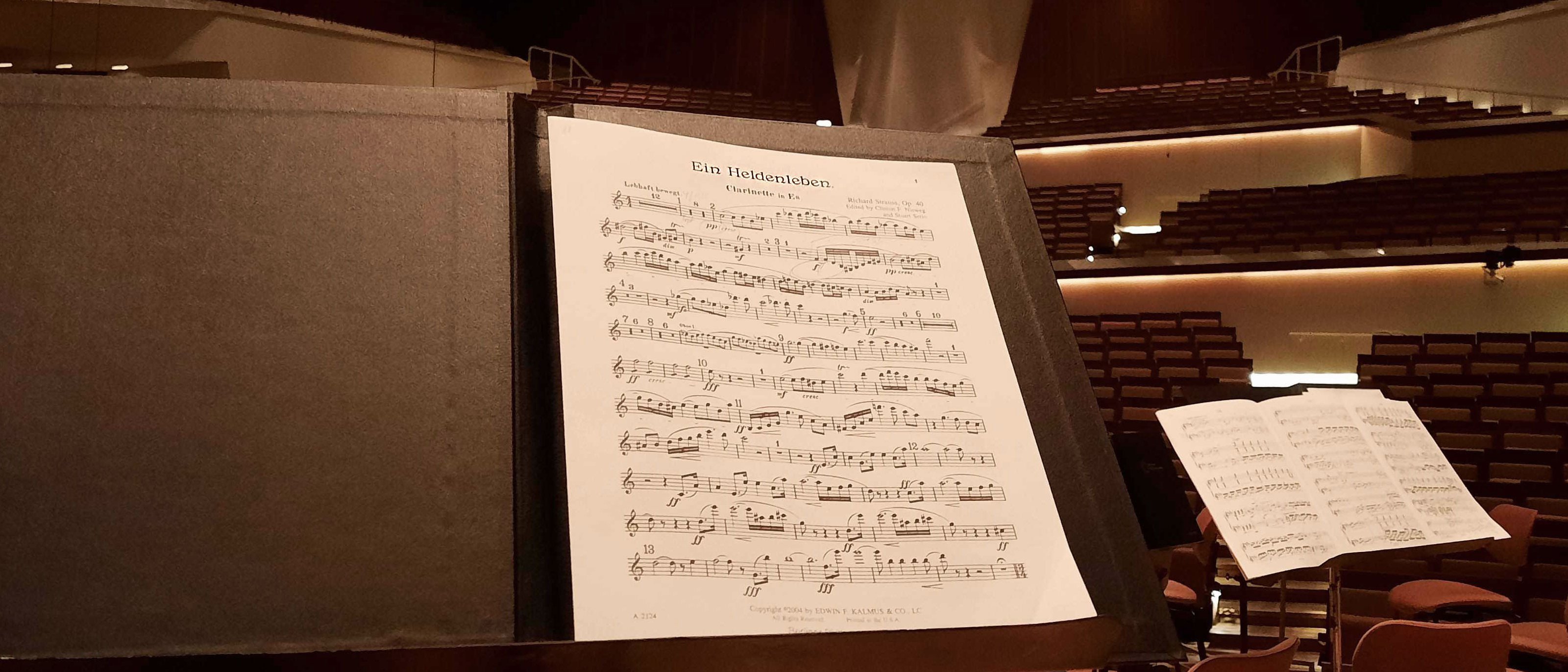

Eight horns, five trumpets, quadruple woodwinds, three trombones, two tubas and harps, as well as strings, timpani and percussion – a very large orchestral ensemble is needed to perform Strauss' Ein Heldenleben. It is not a work which can be easily taken on tour. Nevertheless, the Munich composer’s tone poem has been part of the Berliner Philharmoniker’s musical tour repertoire for almost 100 years. Herbert von Karajan, chief conductor of the Berliner Philharmoniker from 1956 to 1989, was particularly fond of including Ein Heldenleben in tour programmes, whether to Bielefeld, Hamburg, Düsseldorf and Salzburg, to Italy, Spain and France, or even to Japan and the USA.

Self-confident, megalomaniac, sonorous

The young Strauss stirred up a great deal of controversy with his tone poem Ein Heldenleben. When he declared that he found himself no less interesting than Napoleon or Alexander the Great, he was called simply a megalomaniac. The idea of a symphonic poem about a hero who seemed to be none other than himself was daring to say the least. The music also supported the thesis of Strauss’ delusions of grandeur.

Even the self-confident, expansive E-flat major theme aligns him with the great symphonist Ludwig van Beethoven and his “Eroica”. In the chapter “Des Helden Friedenswerke” (Works of Peace by the Hero), he brings together quotations from well-known earlier works such as Macbeth, Don Juan, Tod und Verklärung, Don Quixote and the lied Befreit in an elaborate polyphonic collage – at the very end, we hear the fanfare from Also sprach Zarathustra, and motifs from his unsuccessful, almost forgotten opera Guntram are also woven in. It almost goes without saying that it is Strauss’ wife Pauline (and his courtship of her) who was portrayed in “Des Helden Gefährtin” (The Hero's Companion).

However, “The Hero’s Adversaries” (Des Helden Widersacher), who nag and bleat and ponderously quibble amongst themselves, were seen by contemporary music critics as themselves, and they then went on to do what they did before: they grumbled and moaned.

It was only much later that they recognised what Strauss had achieved with his symphonic poems – a combination of the once incompatible, of “absolute music” and programme music. Ein Heldenleben is not just a self-portrait, but comes close to being a full-blown symphony. The fact that the composer was thinking far beyond a musical autobiography is evident from the fact that he hardly foresaw his own “Des Helden Weltflucht und Vollendung” (Retirement from this World and Completion). Even in one of his last writings, the aged artist noted: “Why don’t people see what is new in my works, how in them, as is found otherwise only in Beethoven, the human being visibly plays a part in the work […].”

Grand entrance for concertmasters

Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben, which is part of the Berliner Philharmoniker’s core repertoire, provides the orchestra with an ideal opportunity to express its brilliance and art of nuance. In addition, the sumptuous score allows the musicians to demonstrate their talent as soloists. Not least, the first concertmasters have a major appearance with the seductive violin solo which depicts the hero’s companion.

However, it has been a while since the Berliner Philharmoniker took Strauss’ tone poem on a major overseas tour: in 2005 it was heard during a tour of Asia with Sir Simon Rattle, and in 2006 during a guest performance in New York. Most recently, Kirill Petrenko conducted the work at the Easter Festival in Baden-Baden in April 2023 – as a prelude to this season, in which the theme of Heroes is a focal point. And Richard Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben could hardly be left out, either in Berlin or on tour.