When you picture buildings that embody global culture, such as the Guggenheim Museum by the American architect Frank O. Gehry in Bilbao, Spain (1997) and the Elbe Philharmonic Hall in Hamburg by Herzog & de Meuron, you can hardly imagine the problems Hans Scharoun encountered in the mid-1950s with his design for the Berlin Philharmonic Hall. And that was not among politicians, who were initially astonished, or enthusiastic architecture experts, but rather most particularly with the engineering and building-site offices. These days, highly sophisticated design computers can effortlessly master the most complicated geometry. Consequently, the digitalisation and computerisation of the construction process has infused the present-day world of architectural images with a design engineering and technical normality that just 20 or 30 years ago would have been laughed off as a crazy fiction that could not be built. That must have happened to Hans Scharoun as well when, somewhat more than 50 years ago, he went public in Berlin with his spatial vision of a concert hall that places the music at its architectural centre.

Ahead of its time

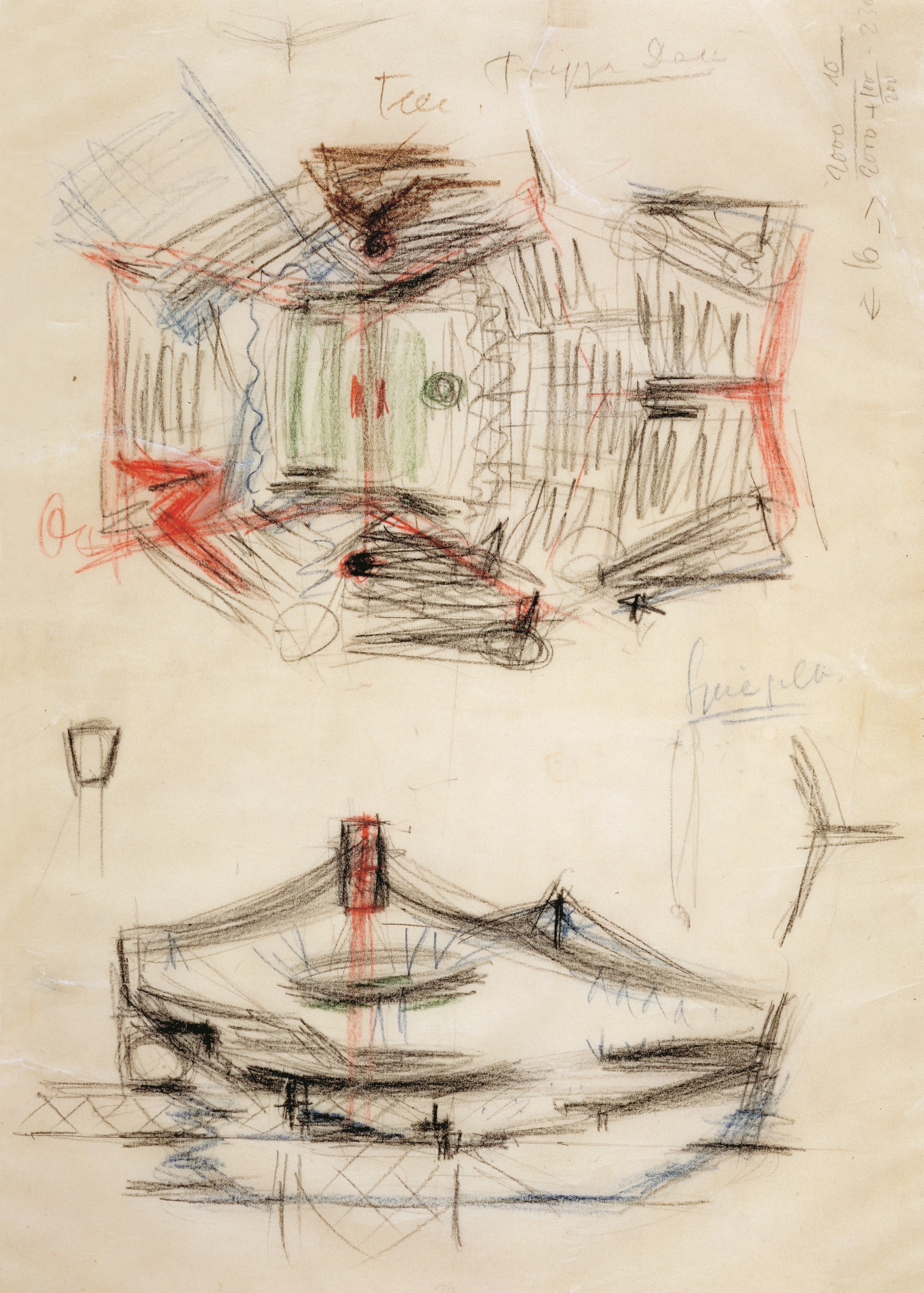

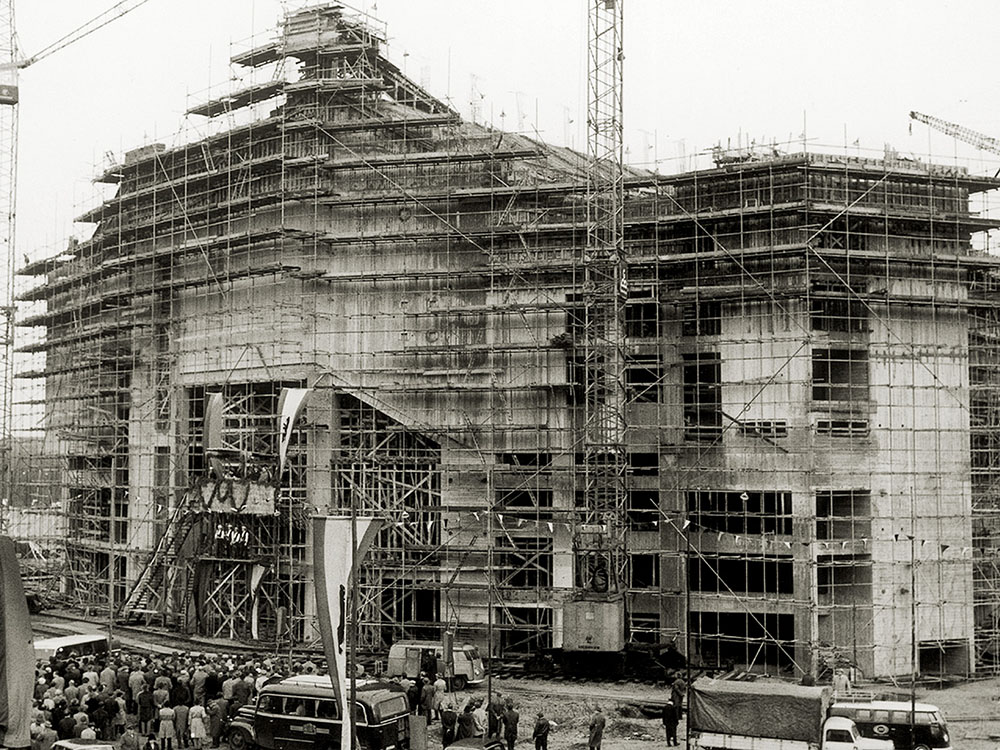

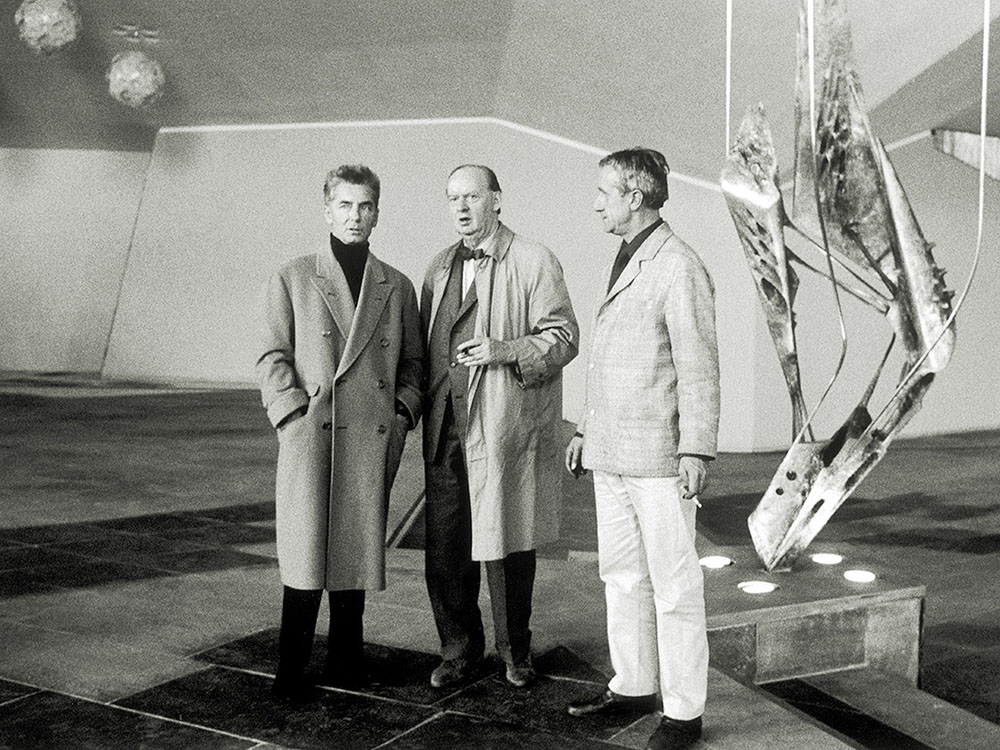

In those days he was de facto still confronted with brigades of draughtsmen who had to render the sketches and drawings he’d dashed off with a thick 3b pencil into measurements and proportions, with cohorts of builders who had to work by hand and set up falsework for forming the concrete, and with engineers who grew up and were trained in the mental space of Euclidean geometry. All expressed reservations and concerns – and not without good reason – about whether the fractal shape composed of hanging and protruding elements that they saw on Scharoun’s drawings and sketches could be transferred into a stable reality of steel, iron, concrete and wood at all. Those who looked more closely saw bends and slopes everywhere, broken lines and edges at flat or wide angles. That this design by Scharoun was literally unfamiliar – who could blame any of the appraisers, master builders and construction workers of the time? None had Smartphones nor tablets that visualise a drawing in 3D using an app. Instead they had only a T-square with ruler and sharpened pencil, a compass and measuring tape with which to approach the great architectural author’s fantasy.

The question of location

At first, the Philharmonie was not designed for its current site at Kemperplatz, but rather as an expansion of the Joachimsthal Gymnasium (secondary school) in Wilmersdorf, a building that is now the University of the Arts on Bundesallee. Scharoun won the competition in 1957. Ten architectural firms took part. After intense debates about both the architecture of the Philharmonie itself as well as of course the costs of the new building, the Berlin Senate took the decision in 1959 to establish a new centre of cultural buildings on the southern edge of the Tiergarten. Even based on the criteria of the day, but most definitely according to today’s criteria, the construction cost – first calculated at DM 7 million, finally after redesign and relocation increased to DM 13.5 and ultimately 17.5 million, was low, perhaps even scandalously cheap.

But the actual reason for relocation to the edge of the Tiergarten was not only, as often rumoured, to come closer to the city centre of Berlin, but was much more prosaic. It was connected with Hans Scharoun’s urbanistic vision, developed as the head of the municipal planning office of the Berlin Magistrate from 1945-47, that has gone down in history ingloriously as the “Berlin Collective Plan”. According to this, when reconstructing Berlin, Scharoun wanted with very few exceptions to tear down all the houses and buildings still standing after the aerial bombardment in order to completely rebuild the city within a huge grid of highways separated according to living, working, administration and culture functions – a nightmare scenario from today’s perspective, though with this vision Scharoun in no way stood alone.

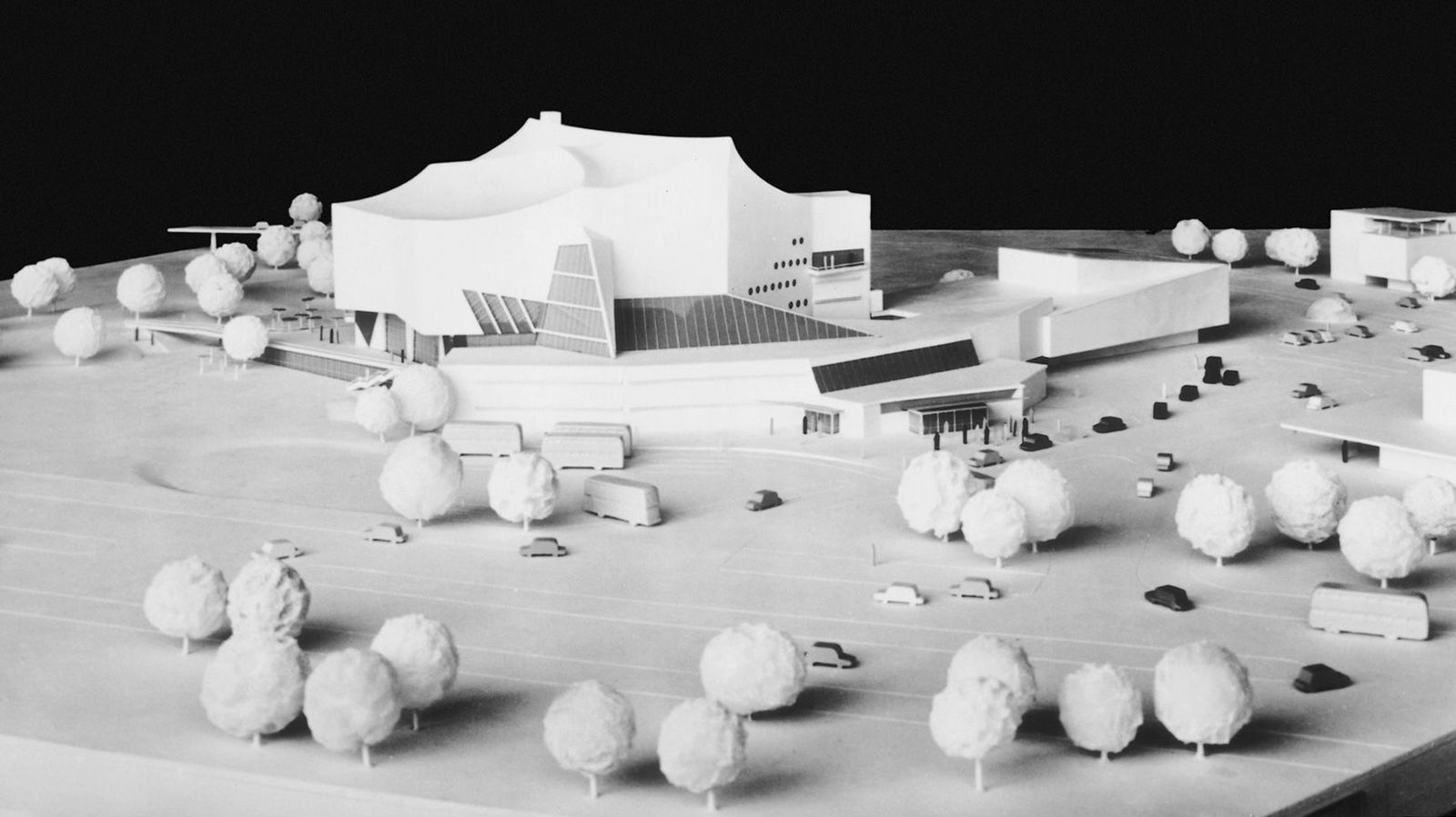

Scharoun did not need to substantially revise his design for the Philharmonie when redesigning for the new location. It was intended to build it as a free-standing building that could be seen from all sides. Nonetheless, it was possible to keep the master pattern of the body of the hall with the orchestra in the centre and a for the most part L-shaped, horizontal shell structure for musicians, administration, instruments and other offices. Scharoun thought radically from within a building, not from its exterior, particularly when it came to the Philharmonie. This attitude towards thinking and design characterises him as a representative of the organic modern era of New Architecture in the 20th century.

Staged space

Only the entrance needed to be roofed and formulated anew, as in Wilmersdorf it would have been through the Joachimsthal Gymnasium. In just this context Scharoun achieved something great in terms of staging and impact. Indubitably, the dramaturgical succession from the entryway covered by a canopy through the softly illuminated ticket office to the darker narrowing for ticket collection, behind which the foyer opens up, bright and festive of an evening, lively in an urbane and vitalizing way, is a tour de force in terms of the psychology of space. It generates an excited anticipation to which one can ascribe almost erotic qualities. Strolling or hurrying through the foyer and up and down various stairways, galleries, balconies and bridges, a climax is prepared in several stages that culminates upon entering the auditorium. Wherever one enters the large hall, be it in the blocks situated higher along the sides or in the lower ones, walking through the relatively inconspicuous covered accessways releases in a liberating way the tension which has been building and is retained when moving through the architectural space. That too, and not just the formal polymorphism of shapes and forms and the bold height of the hall, make it one of the most impressive and significant spatial creations of the 20th century in the whole world.

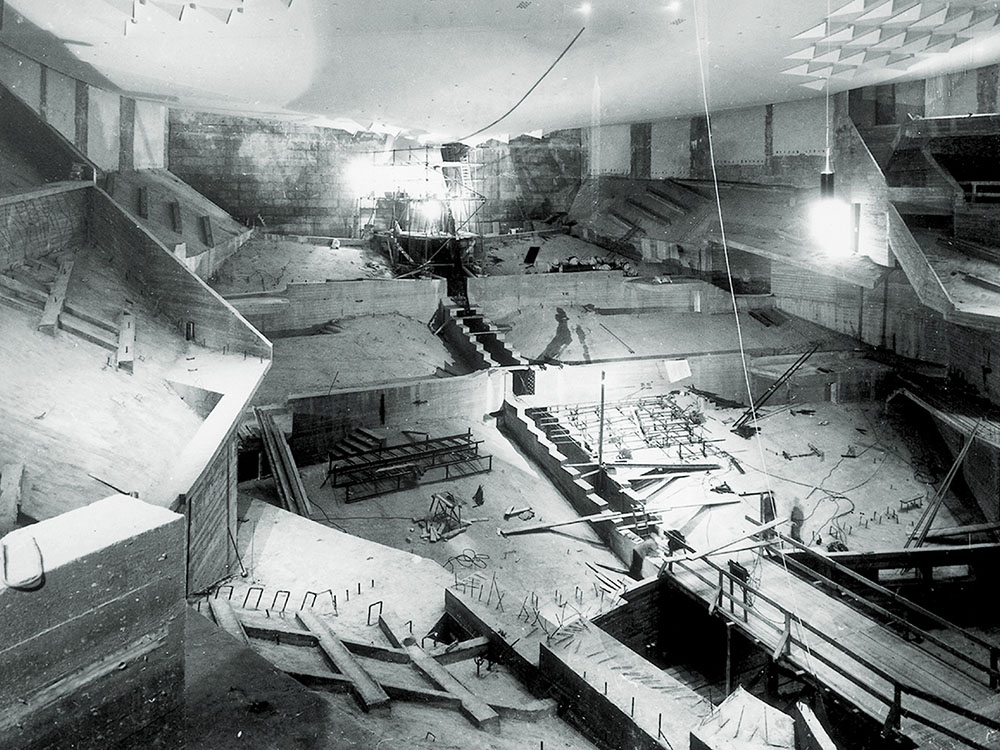

Attempts have frequently been made, particularly after the Philharmonie was opened, to describe and capture in pictures the crystallized nature of the gallery and audience “slopes”, the tent form of the ceiling, the slopes and suspensions of the heavyweight and lightweight parts of the hall that are difficult to understand. Scharoun’s own imagery of a “valley at the base of which can be found the orchestra, surrounded by ascending vineyards” of the audience blocks has retained its poetic character, though its landscape pathos has become alien to us in an architectural context. The threefold interlacing of the pentagons Space – Music – People that has become the sign of the Philharmonie is also believable and beautiful as the architect’s intention and as an intangible reference, but has no evident nature in terms of the visual use of space.

Transparent, harmonious, festive

What may instead have been decisive is that this room composed of so many facets, with a unique inner porousness and complete permeability of all the audience blocks among each other, intuitively forms a harmonic space for the beholder – without overwhelming. “Remember the impression of good architecture,” the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein noted, “namely, that it expresses a thought. You would like to follow it with a gesture.”

In the Philharmonic Hall, this gesture has the character of a harbouring festiveness. It is without dispute that the Berlin Philharmonie has stood the litmus test of time, both outside and in. Yes, it can be cited as an example of the paradox of temporality in architecture. Just because Hans Scharoun, experienced in architecture and in his own life, rigorously decided – without casting an eye towards how long it would last or whether it would be eternal – in favour of its own contemporaneity, it became possible for his work to acquire the timelessness we still enjoy and admire today.

60 years of the Philharmonie Berlin

Sounding Space

About the acoustics of the Philharmonie

“A matter of the heart for the whole of Germany”

A citizens’ movement initiated the reconstruction of the Philharmonie Berlin

How to get to the Philharmonie Berlin

Whether by bus, train, bike or car: Here you will find the quickest way to the Philharmonie Berlin – and where you can park.