During an early stage of his work on the Philharmonie, Hans Scharoun had already enlisted the services of Lothar Cremer. An expert on acoustics, Cremer was then head of the Institute for Technical Acoustics at Berlin’s Technical University and was initially sceptical about Scharoun’s basic idea: the architect, he felt, had given less thought to the “acoustic aspects” of the hall than to the question of “creating a new society”. From his expert standpoint, Cremer felt “obliged to dissuade Scharoun from his decision to position the orchestra centrally and at the same time to draw his attention to possible acoustic complications”. Although Scharoun refused to give ground on the main issue, he was none the less “willing to do everything to further his idea”. He was venturing into hitherto uncharted territory, a move that “understandably appealed to the scientist” in Cremer, so that the latter finally agreed to accept the challenge that he had been set.

In this, the demand for a reverberation time of two seconds proved the least of his problems. Reverberation is something that can be calculated. It depends in part on a whole series of factors affecting the more or less sound-absorbent properties of the materials used, including the seating. But above all it depends on the volume of the hall. The deciding factor in calculating the reverberation time is the average air space per person. In the case of a capacity of 2,250 seats, the “acoustically necessary” volume of the Philharmonie’s auditorium is 26,000 cubic metres. (It is “necessary” in order to achieve the required air space of around 10 cubic metres per person.) The precondition for this was achieved by raising the height of the ceiling, which stands at 22 metres above the platform.

Vineyard terraces, clouds and pyramids

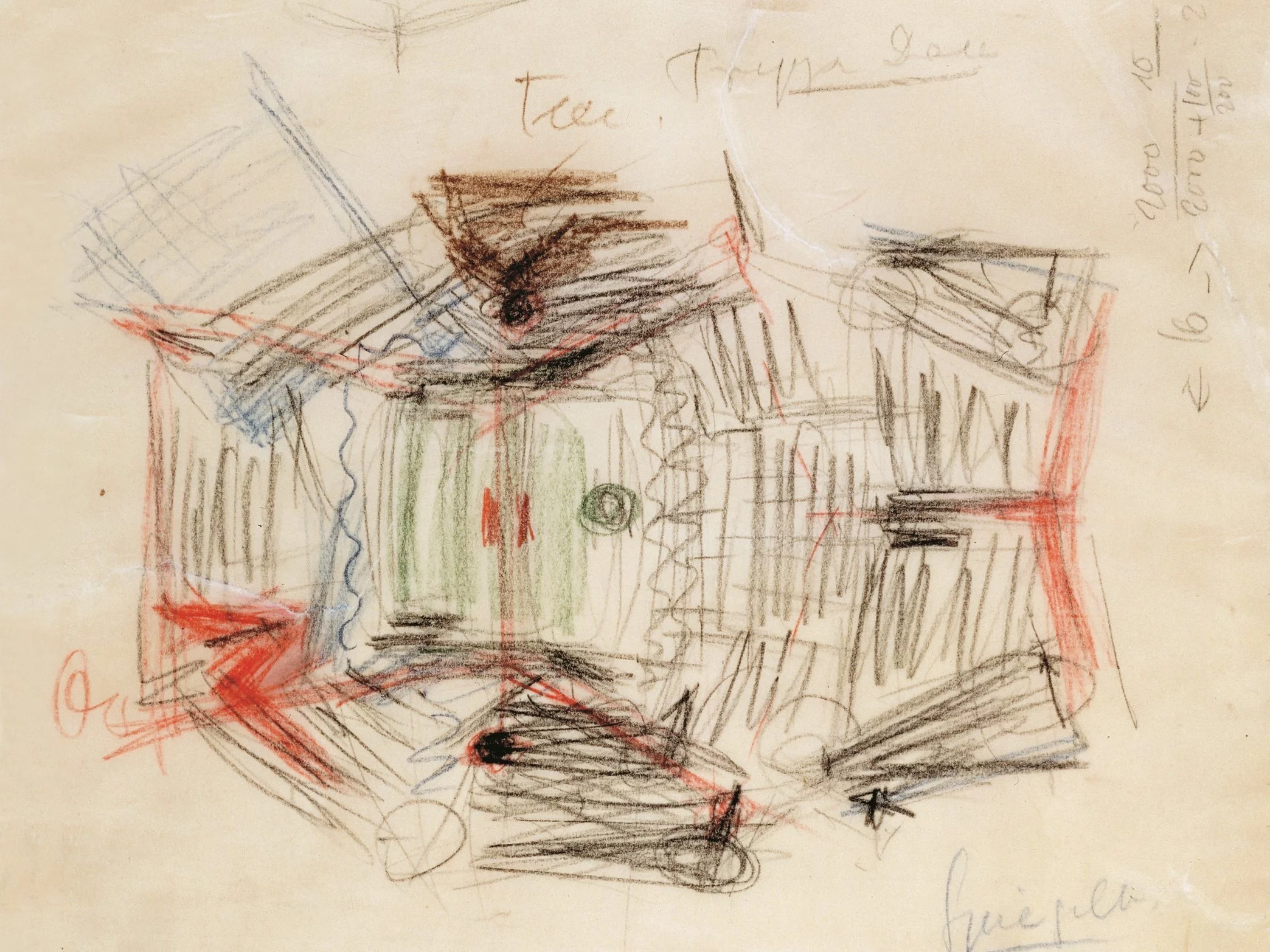

A more serious problem was that of ensuring that the musicians could hear each other. This contact is naturally easier to achieve in a hall whose platform is framed by straight walls than in a space that is open in every direction. Cremer once explained the underlying problem by reference to two skiers, one of whom follows in the other’s tracks in new snow: “If there were no reflexes,” the man at the front would be able to understand the man behind, but the latter “would understand virtually nothing”. In view of the specific directional characteristics of particular instruments such as violins, trumpets and especially the human voice (acousticians speak of “preferential direction”), the Philharmonie auditorium required the reflections to be graded in a specific way. These reflections are perceived by the musicians as the room’s response. In order to prevent the sound from being dispersed in only one direction, reflective surfaces, projecting gradations and balustrades were fitted to the “vineyard terraces” behind and on both sides of the podium; Cremer also demanded that a reflector be fitted above the orchestra as the ceiling of the hall is too high at this point to reflect back the sound and disperse it.

It was originally planned to use a single reflector, but this would have cut the space in two in an unacceptable manner, and so ten “clouds”, slightly curving downwards, were suspended at a height of 12 metres above the platform. At the same time, the tent-like ceiling of the hall, which is made of three convex arches, helps to ensure that the sound is equally diffused around the hall. The “pyramids” that are fitted around the edges of the ceiling and that are packed with material to absorb low frequencies serve this same purpose. Edgar Wisniewski has emphasized the “countermovement between the rising rows of the stalls and the shape of the ceiling as it glides down”, as a result of which the sound waves “are necessarily diffused in a highly concentrated form to the most distant seats as well”. These measures have all played an important role in ensuring that listeners in the blocks of seats behind the platform are more or less equally able to hear the music emanating from the middle of the hall.

However much the acoustics of a hall may be calculable, the space, when filled with music, is also a scene of life and movement: living movement as well as inner emotion resonate within the space. In short, many subjective factors are at work when the process of attuning one’s ears to a new hall begins. In the case of the Philharmonie, too, opinions changed, and the acoustics were generally felt to be better at a later stage than at the beginning. Even so, there remains an acoustic risk: when it became known that a movement from a string quartet was to be performed as part of the opening ceremony, all the parties concerned immediately expressed their concern and wondered whether so large and wide a hall was compatible with the intimate sonorities of chamber music. When consulted on the issue, the expert responded with a shrug of his shoulders: he had no idea. The quartet is said to have sounded wonderful.

From Berlin into the world

Once initial problems with the hall’s acoustics had been ironed out to the satisfaction of all concerned, the Philharmonie Berlin was very soon being used as a venue both for sound recordings and television broadcasts. Today the hall has a modern digital sound studio for live concerts and radio broadcasts. Here, too, the sound for the Digital Concert Hall is mixed. Numerous microphones are installed in the hall. They are suspended from the ceiling over the platform and are operated by remote control. In addition to the sound studio there is also a sound-processing studio and a video studio for the Digital Concert Hall that is likewise equipped with the most modern technology.

The inaugural concert of the Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall was streamed live on the internet on 6 January 2009, ushering in an unprecedented project that enables people all over the world to enjoy the orchestra’s concerts in the best possible video and audio quality. Events can be followed in subscribers‘ own living rooms by means of compatible television sets and Blu-ray equipment as well as by computer. For the Digital Concert Hall seven high-definition cameras were installed in the auditorium, all of them remote-controlled from a studio under the roof. Made for the exclusive use of the Digital Concert Hall, these high-definition recordings are then streamed on the internet using the most up-to-date encoding technology and in the best possibile quality. Well-known directors are entrusted with the task of providing appropriate images for the musical experience. Some forty concerts are broadcast live every season, while many more live recordings are available in a constantly growing archive that also includes interviews with artists. All can be accessed from this virtual concert hall.

Space - Music - People

About the architecture of Hans Scharoun's Philharmonie

“A matter of the heart for the whole of Germany”

A citizens’ movement initiated the reconstruction of the Philharmonie Berlin

How to get to the Philharmonie Berlin

Whether by bus, train, bike or car: Here you will find the quickest way to the Philharmonie Berlin – and where you can park.