- Introduction

Elijah is one of the most complex figures of the Old Testament. But more than that, he is also revered by Jews and Muslims as a fighter against idolatry. His spectacular ascension in a chariot of fire led to him becoming adopted as the patron saint of aviation – and the protagonist of Felix Mendelssohn’s oratorio. The Berliner Philharmoniker present the work this week under the baton of Kirill Petrenko and with Christian Gerhaher in the title role.

An angry prophet, but also a man full of doubts. A zealot who calls to kill, and yet a person who demonstrates compassion and kindness. The title character in Felix Mendelssohn’s oratorio Elijah is not an unyielding figure of stone, but a real flesh-and-blood character. Mendelssohn’s visionary music with its depictions of storms, earthquakes, floods and fire throws itself into this Old Testament story with elemental force, but it doesn’t forget moments of consolation. As a result, Elijah became unrivalled as the most popular oratorio of the 19th century.

In icons of the Eastern Church, the bearded Elijah sits alone in the forest and looks expectantly at a raven that brings him food; in a painting by Lucas Cranach, on the other hand, he stands in the middle of a teeming crowd and successfully challenges the priests of the idol Baal. Elias, Elia, or Elijah means something like “My God is the Lord”. And this man of God bears witness to that, whether as a hermit or as a thundering prophet.

Known in all world religions

Felix Mendelssohn and his librettist Julius Schubring based their oratorio Elijah essentially on the Old Testament account as handed down in the 1st and 2nd Book of Kings. The historical model for the figure was probably an itinerant preacher from East Jordan who worked in Israel around 850 BCE and was regarded, among other things, as a magical rain-maker. With fervent zeal, prayers and fasting, he propagated the exclusive worship of Yahweh and incited the oppressed rural population against the corrupt King Ahab. According to the Bible, Elijah did not die an earthly death, but rose to heaven at Jericho in a chariot of flames with fiery horses. In later times, this spectacular ascension would link him to power over thunderstorms and fire, and he also became the patron saint of aviation. Likewise, steam trains in Germany used to be called colloquially a “feuriger Elias” (fiery Elijah).

Elijah is not only significant for Christianity; he is also venerated by Jews and Muslims as a fighter against idolatry. In Judaism, he is also seen as the harbinger of the Messiah, which is why a cup is prepared for him at Passover in the event of the prophet’s appearance. All this makes him an impressively multifaceted figure. As the range of his portrayal from the pious hermit on the icons to Cranach’s fiery popular orator shows, Elijah was a pugnacious prophet, a fighter ready to use violence, but also an enlightened ascetic who needed nothing to survive but faith in God.

The plot in the oratorio

In Mendelssohn’s oratorio, the narrative around Elijah unfolds like this: Ahab, king of Israel in the 9th century BCE, has turned with his people to the weather god Baal. Ahab’s wife Jezebel, in whose Phoenician homeland this cult was already widespread, had a great influence on this. Ahab built temples and altars to Baal and thus angered God (or Yahweh, as he is called in the Old Testament). His prophet Elijah now wants to lead the people back to the true faith. The oratorio begins with his threat that Yahweh will send a drought.

The people of Israel suffer from the lack of rain. Obadiah, King Ahab’s palace chief and Elijah’s ally, calls on the worshippers of Baal to repent. An angel orders Elijah to hide by the brook Chorath, where ravens feed him. When the brook dries up, he goes to the city of Zarepath on the angel’s instructions. There he meets a widow who provides him with food and drink from a jar of oil that never empties. When the widow’s sick son dies, she reproaches Elijah for having come only to bring misfortune. But Elijah brings the dead child back to life and the widow recognises him as an emissary of God.

In the third year of the drought, Elijah demands of King Ahab a contest of the gods. On Mount Carmel, Yahweh and Baal are invoked by their worshippers to ignite a prepared sacrifice. Three times Baal is asked by the people for a sign, but it does not come. Then Elijah prays to his God, who causes fire to fall from heaven. The people confess their faith in Yahweh. At Kishon’s brook, the prophets of Baal are killed on Elijah’s command. Queen Jezebel laments the people’s renunciation of their faith.

Obadiah asks Elijah to end the drought, whereupon the prophet orders a boy to look for rain. At first the boy sees nothing in the sky, but at last he sees a cloud announcing the storm that will lead to their salvation. Gratefully, the people celebrate the heavy rains.

At the beginning of the second part, a voice calls the people not to fear God. Elijah announces to King Ahab that the Lord will punish him for his transgressions, prompting Queen Jezebel to stir up the people. The mood turns against the prophet and Jezebel calls on the people to kill Elijah. Obadiah warns him of the threat and urges him to seek refuge in the desert.

While fleeing, Elijah realises that his attempt to convert the people was in vain. He longs for his death. But angels protect him and urge him to go to Horeb, the mountain of God. On the way, Elijah begs his Lord to reveal himself to him. The approach of God produces storms, earthquakes and fire, but he himself reveals himself with a “gentle whisper”. God commands Elijah to go back to Israel and gather there the seven thousand left behind who oppose the Baal cult. Elijah overthrows the king, persuades the people of Israel to repent and is taken by God to heaven in a chariot of fire. The oratorio ends with praises to the Lord.

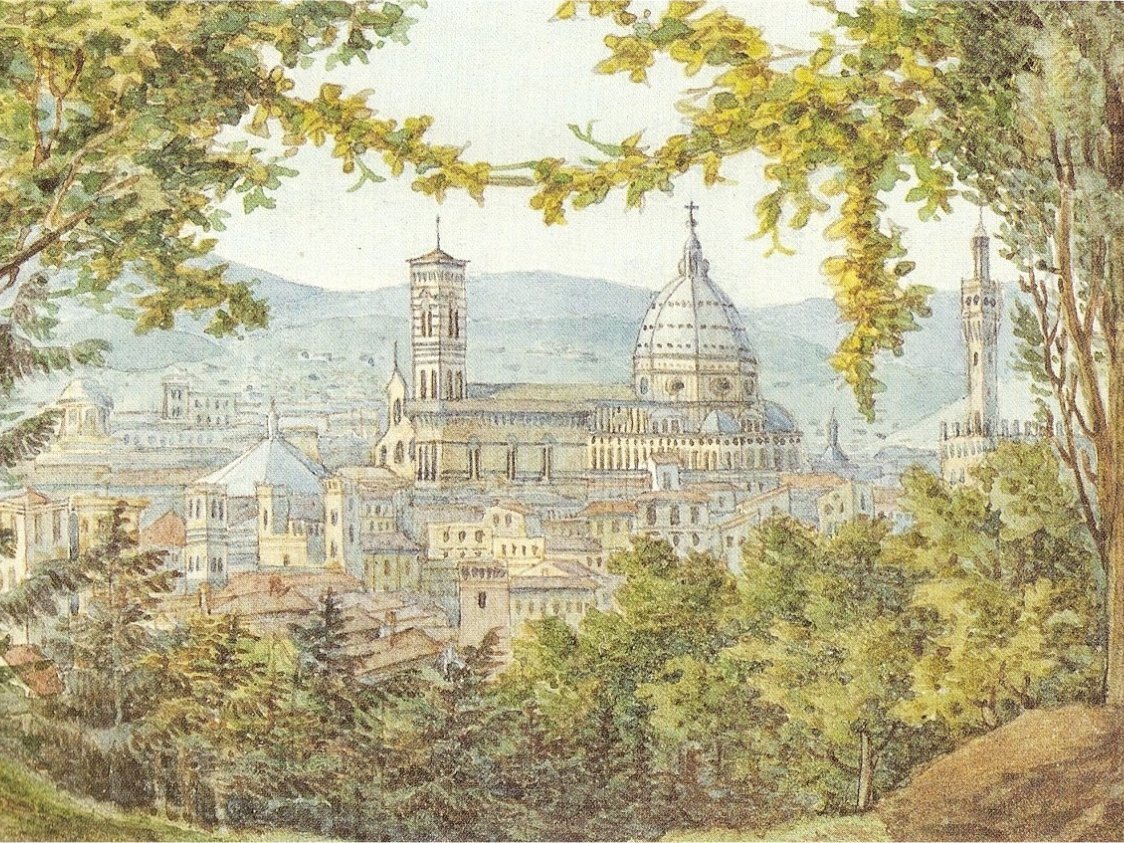

Felix Mendelssohn as traveller

Mendelssohn went on a three-year educational trip in his early twenties and brought back a great deal of inspiration for his later works.

5 questions about “Also sprach Zarathustra”

Read five things you didn't know about this famous tone poem by Richard Strauss.

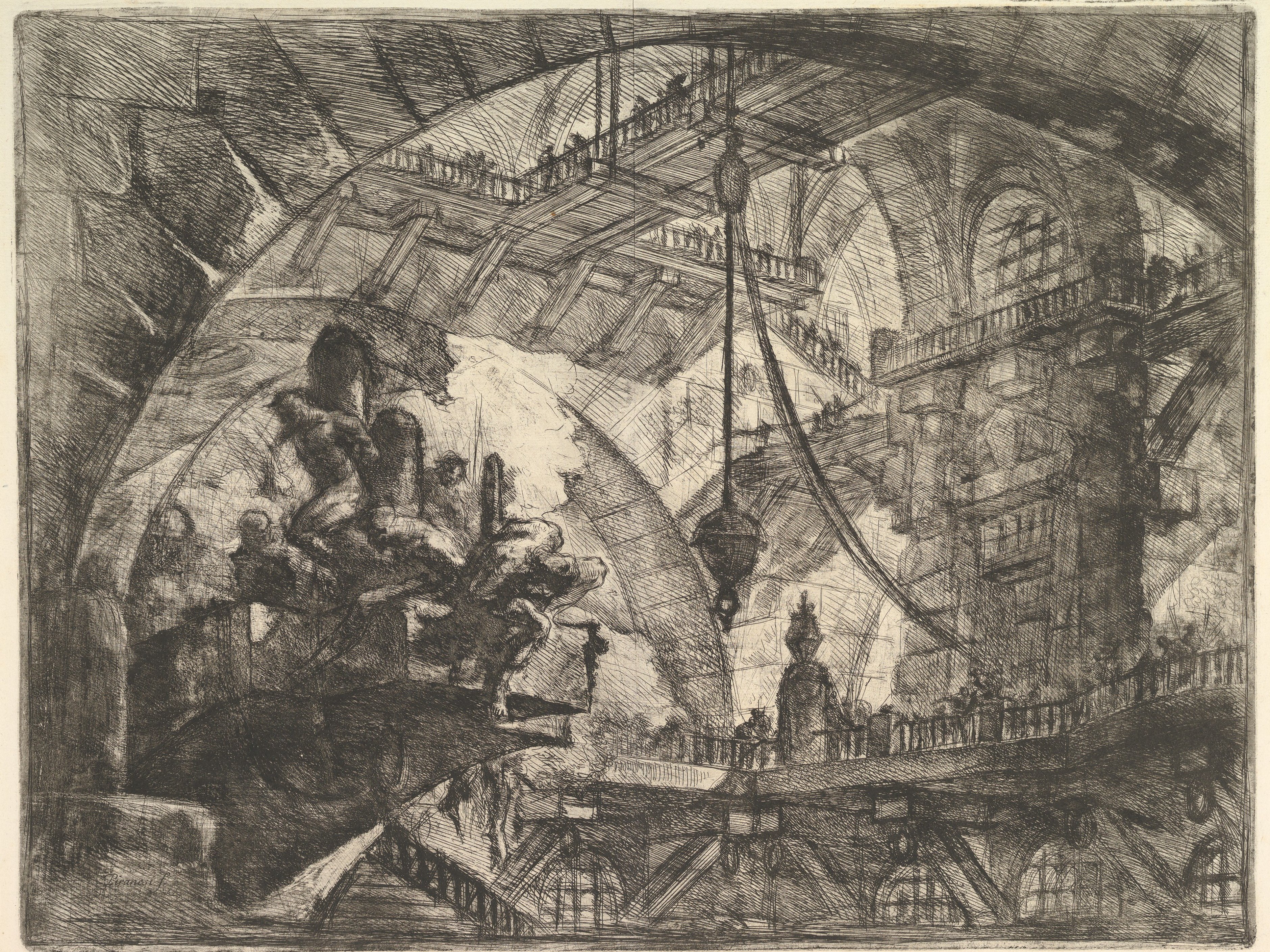

Dallapiccola's Il prigioniero

Introduction to the expressive short opera “The Prisoner”.