Russian Modernism reads as a rich and complex musical landscape, shaped by innovation, political turmoil, resilience and exile. From the bold experiments of Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev to the coded defiance in music by Dmitri Shostakovich and Mieczysław Weinberg, works from this era reveal the power – and peril – of creative expression under extreme conditions.

Russian modernism: We think of the brash chords of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the ferocious bashing of Alexander Mosolov’s futuristic Iron Foundry, the fury behind Shostakovich’s grim repression. We might also think of the bloodshed and horror of the Russian revolutions of 1917, and of the brutal denunciations of Stalin’s Great Terror. How has one term come to embrace so much contradiction? The Berliner Philharmoniker’s Flex Package offers listeners the opportunity to explore the era through their own selection of its diverse musical expressions.

Paradoxically, when dictators truly believe in the power of music, composers suffer. Stalin’s conviction that music was important to his politics, turned acts of creativity from free expression into life-threatening risks. The perils of state censorship became a source of the utmost fear to Soviet composers; and their differing responses to the danger have become inseparable from our perception of Soviet musical modernism.

Prokofiev’s homecoming and disillusionment

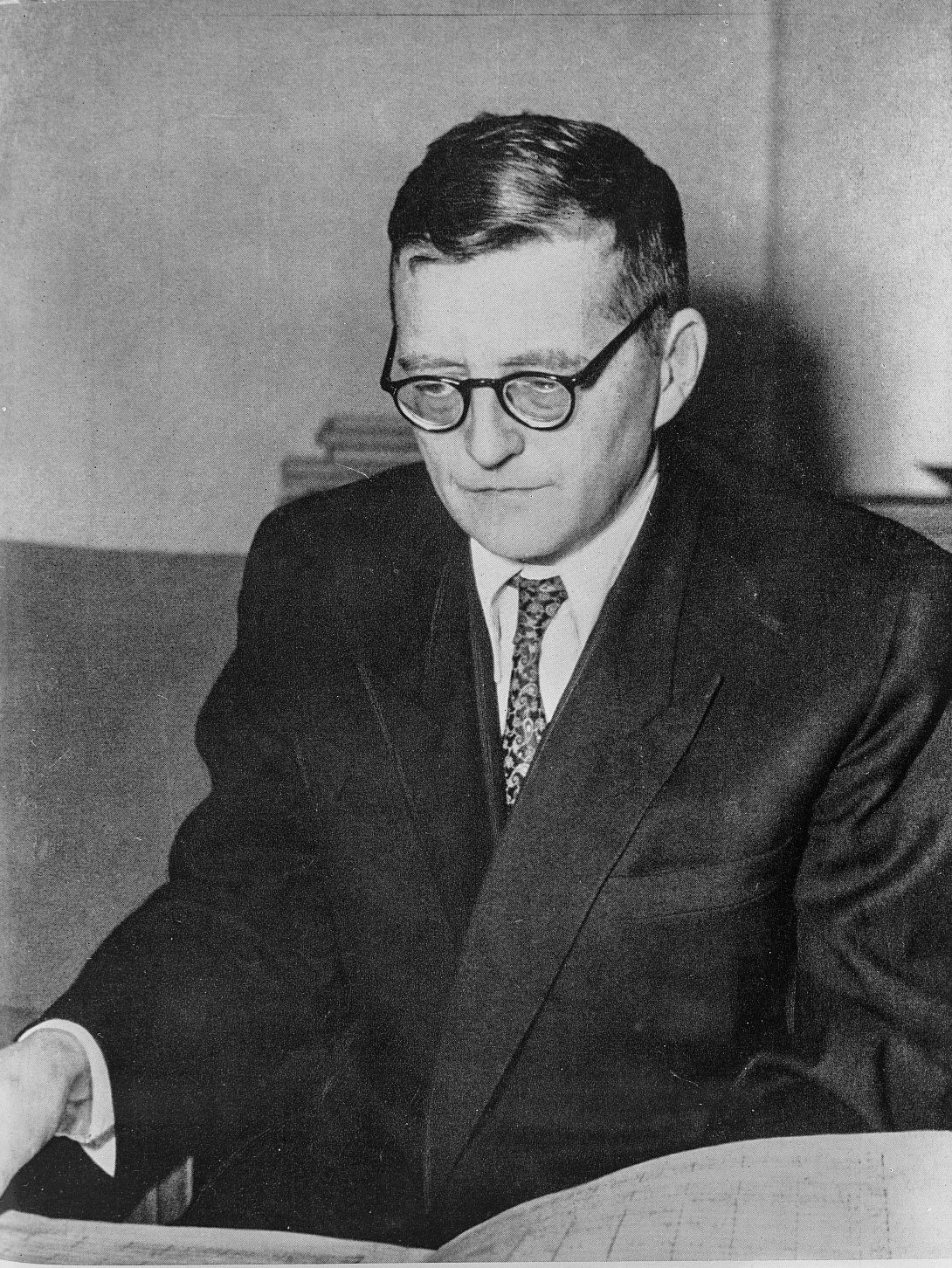

Shostakovich, following the denunciation of his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, slept on a narrow couch in his hallway, next to a packed suitcase, hoping that his family would not be woken up when the secret police came to take him away; they always came at night.

Prokofiev was just completing the piano score of his opera Semyon Kotko when he received word that the opera’s producer, Vsevolod Meyerhold, had been arrested. Meyerhold was tortured, then executed; his wife was murdered.

In 1936, he had returned from his unhappy exile in Paris. Where he was eclipsed by Stravinsky, homesick, and courted by a Soviet establishment that promised a country eager for his work. He must have imagined Russia as a place where his own brand of angular modernism would be welcomed. “Soviet life has evolved positively, and my sympathies are with it,” he wrote in his diary on the cusp of his return. “I want to write music that will be understood by a broad audience.”

Stravinsky in Exile – A Different Path

Stravinsky’s success in Europe, by contrast, rested on a wholly different approach. His aim was not to be easily understood, but to stir and unsettle. Nowhere was this more evident than in the furore surrounding the 1913 premiere of Le Sacre du printemps – an occasion that descended into outright brawls in the auditorium. Le Figaro’s Henri Quittard dismissed it as “a laborious and puerile barbarity”.

Perhaps the Paris audience had been lulled by the Stravinsky’s more palatable Firebird and Petrushka (1910 and 1911), where rough Russian folklore met bold, innovative orchestration; this was a gentler form of modernism. But by 1920, when Stravinsky wrote Pulcinella, Russia had been torn apart by revolution and civil war. Stravinsky had turned his back on Russia, and would never return. Instead, he fled reality by flirting with neoclassicism, and carefully avoided conversations about Russian politics for the rest of his life. Prokofiev, meanwhile, was being courted by the Soviet Establishment, and had received a commission from the Kirov Ballet.

Artistic Survival under Stalin

The fate of Romeo and Juliet would become emblematic of Prokofiev’s disillusionment. The Kirov collaboration fell through, the Bolshoi deemed the score “impossible to dance to,” and the Soviet premiere was delayed until 1940. The ballet, instead of launching a happy homecoming, marked the start of the composer’s artistic tensions with his homeland.

Shostakovich, stuck at home while had Prokofiev toured the West, was already feeling the Soviet shift towards ideological control when he wrote his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1933. Though Stalin's Great Terror was yet to come, composers faced mounting pressure to avoid “formalist” experimentation. The piece, originally intended as a trumpet concerto, evolved into a witty double concerto. Its playful surface masked deeper unease. At its premiere, Shostakovich’s light irony was still tolerated. But he had already begun work on Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which would lead to his denunciation in 1936.

During the Great Terror (1936-1938), over 700,000 people were executed; millions more were sent to labour camps. Composers faced a choice between compliance and annihilation. Shostakovich navigated between public loyalty and private defiance, encoding protest into music that could pass official scrutiny. Prokofiev, by contrast, believed he could work within the system. His attempts at conformity, including the Cantata for the 20th Anniversary of the October Revolution (“Sing of our dear Stalin, glorify him in song…”), lacked Shostakovich’s subversion. Prokofiev paid a personal price, as friends and family suffered under the regime.

After Stalin: cautious experimentation

In a bitter twist, Prokofiev and Stalin died on the same day – 5 March 1953. National mourning for Stalin meant Prokofiev’s funeral was scarcely attended; flowers from his sparse memorial were reportedly taken to bolster Stalin’s.

Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 was composed immediately after Stalin’s death and is widely read as his reckoning with the dictator’s tyranny. Its furious second movement may be a musical portrait of Stalin himself – brutal, relentless, mechanical. The symphony marked Shostakovich’s reclamation of a personal, unsanctioned voice, though he knew better than to be overtly triumphant. It is a work of internal exile.

Khrushchev’s “Thaw” allowed for cautious experimentation, but ideological boundaries remained. Shostakovich, ever the master of subversion, navigated this uncertainty with the same wary precision that had kept him alive under Stalin.

His Suite for Variety Orchestra, often dismissed as light entertainment, is saturated with sardonic undertones. Its chamber arrangement for piano trio and percussion sharpens the contrast between surface joviality and underlying tension.

As Brezhnev's era took hold, Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 15 (1971) became a final, enigmatic act of defiance. Filled with quotations and private codes, it is less a grand statement than a whispered reckoning. The chamber version exposes its skeletal textures, rendering its quiet resistance all the more stark.

Shostakovich’s contemporary Mieczyslaw Weinberg was long overshadowed by his more famous friend. Weinberg’s Burattino Suite, drawn from his children’s opera, appears innocuous, but masks deeper themes of resilience and deception. Composed during Khrushchev’s Thaw, it reflects the narrow space artists like Weinberg could claim for personal voice – a space shaped as much by caution as by creativity.

Survival as a form of Modernism

Across this programme, Russian modernism reveals itself not as a singular aesthetic but as a shifting negotiation with power. From Stravinsky’s experiments in exile to Shostakovich’s coded survival, from Prokofiev’s failed compliance to Weinberg’s quiet allegories, these works trace a line from outward revolution to inward exile. They remind us that modernism in Russia was never just a question of style; it was, for many, a question of survival.

The Networkers

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Russian composers pursued connections with the Western musical world, often as a response to the impending revolution, but also motivated by curiosity and a desire for intercultural dialogue.

Fresh faces on the Philharmonie stage: The debuts of the 2025/26 season

Each season, the Berliner Philharmoniker welcomes new artists for the first time. Our article takes a closer look at the new faces of the upcoming season.

Flex package: Controversial

Music as a matter of dispute: Discover captivating concerts exploring artistic contrasts and legendary scandalous works in this flex package.