- Portrait

At the beginning of December 2023, Robin Ticciati made his long-awaited debut with the Berliner Philharmoniker. For the artistic director of the neighbouring Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester, idealism is an important factor in his work. “All should play as if it’s the most important thing in their lives at any given moment.” A portrait.

Not long ago, Robin Ticciati thought that his career might be over. In 2016, he suffered a slipped disc. Surgery followed; he was off work for almost a year: “I had this feeling that I might never be able to conduct again.” A feeling like that can become enervating and obsessive. Then came a moment when Ticciati was lying stretched out on the floor of his hotel room that proved decisive. He was listening to the Andante from Mozart’s D major Violin Concerto: “and my face was bathed in tears,” he recalls. It became clear to him just how closely music is bound up “with the way in which your body and mind operate,” he explains. It is a merciless alliance, but it can also trigger an intense feeling of happiness. Fortunately, his career was not over.

Brief moments with profound impacts have often left their mark on Ticciati’s life. In his teens he played the second violin in the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain, and was rehearsing Sibelius’s First Symphony. On the podium was a man known for his calm and kindly manner: Colin Davis. “I was completely overwhelmed by his presence. In his mind he played practically every instrument from the conductor’s desk.”

Conducting – that’s what I too want to do

A seed had been planted; Ticciati felt it. “I want to do that too!” He was already trained in piano, violin and percussion. His decision to turn to conducting soon bore fruit. While he was still a student he conducted a choir at St Paul’s School in London. It was in London that he was born in 1983, an Englishman with Italian forebears. His grandfather was from Rome, where he worked as a composer and as an arranger: “Italian culture is still somehow a part of me.”

Ticciati’s rise to the top tier of conductors was meteoric. In 2005, at the age of 22, he conducted the Filarmonica della Scala in Milan - as the youngest conductor in the venerable history of the house. A year later he made his debut at the Salzburg Festival, causing a domino effect which led to several long-term positions: with the Gävle Symphony Orchestra, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and, in parallel, as principal guest conductor of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra. By 2014 he was music director of the Glyndebourne Festival.

Fluid movements

Anyone observing Ticciati as he stands in front of an orchestra will be struck by his relatively relaxed gestures. His movements exude a sense of fluidity and of something entirely natural. It is no accident that his body language recalls that of Claudio Abbado: “Abbado’s way of conducting, especially towards the end of his life, had something profoundly spiritual about it,” Ticciati says. “His movements were fluid, and they were also beautiful to look at. He had the ability to inspire an orchestra to give its best for him.”

Occasionally – and somewhat superficially – Ticciati has also been compared with Abbado’s successor in Berlin: Simon Rattle. Their hair, to be fair, is similar. But curls aside, Rattle has done much to support his British compatriot. He once said: “Robin is a mensch.” It is a remark that speaks volumes.

Music director in Berlin

Ticciati came to Berlin in 2014 when he first conducted the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester in a performance of Bruckner’s Fourth. Was it love at first sight? “When I arrived at the first rehearsal and raised my baton,” Ticciati later recalled in an interview, “I sensed that this was a group of people who wanted to know exactly what I would like to do.” The players were “open, emotionally-driven and ebullient in the way that they reacted to the music”. Just over a year later he signed a contract with them, and officially took over as their new principal conductor in 2017.

Ticciati, once an inveterate Londoner, found an apartment in Prenzlauer Berg. He quickly became aware of one of the orchestra’s problems: its inability to retain some of its most talented musicians, for whom the orchestra served as a springboard for positions in higher-ranking orchestras. But Ticciati sees this as a virtue: “A part of their DNA is this wildness; as soon as they see a challenge, they’re driven to say: ‘Yes, please.’ This is a characteristic that’s typical of Berlin.”

By 2020 Ticciati had extended his contract with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester, which was now set to last until 2027. But by spring of this year there were rumours circulating that he would jump ship, leaving by the summer of 2025. The move could not have been motivated by any lack of success, since his work with the players has changed the orchestra, above all in terms of the sound that it produces. According to one music magazine, Ticciati has “heated it up by several degrees Celsius”: “They now sound more natural and warmer but are still wonderfully translucent.”

One of the most important virtues: idealism

Ticciati has never wanted to impose his wishes upon his players: his approach is more to persuade them to listen to one another. This it does not always require many words: “Sometimes it’s with a smile that you achieve the best results at a rehearsal.” Or a glance. Or a brief chat after the rehearsal; a quick embrace to express gratitude. “I’d like to keep motivating the musicians, so that they, too, play a part.” They should “all play as if it’s the most important thing in their lives at any given moment.”

Everyone wants to be “pushed” in order to realise a collective vision. At the same time there must be no doubt that what the conductor considers the best possible interpretative approach is also the best possible way for the orchestra. A conductor needs to be aware of the value of idealism; but there should never a sense of routine. Total intensity in the here and now; that is Robin Ticciati’s credo.

Klaus Mäkelä, the Man Who Knows No Fear

In April, the Finn Klaus Mäkelä makes his debut with the Berliner Philharmoniker with works by Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich.

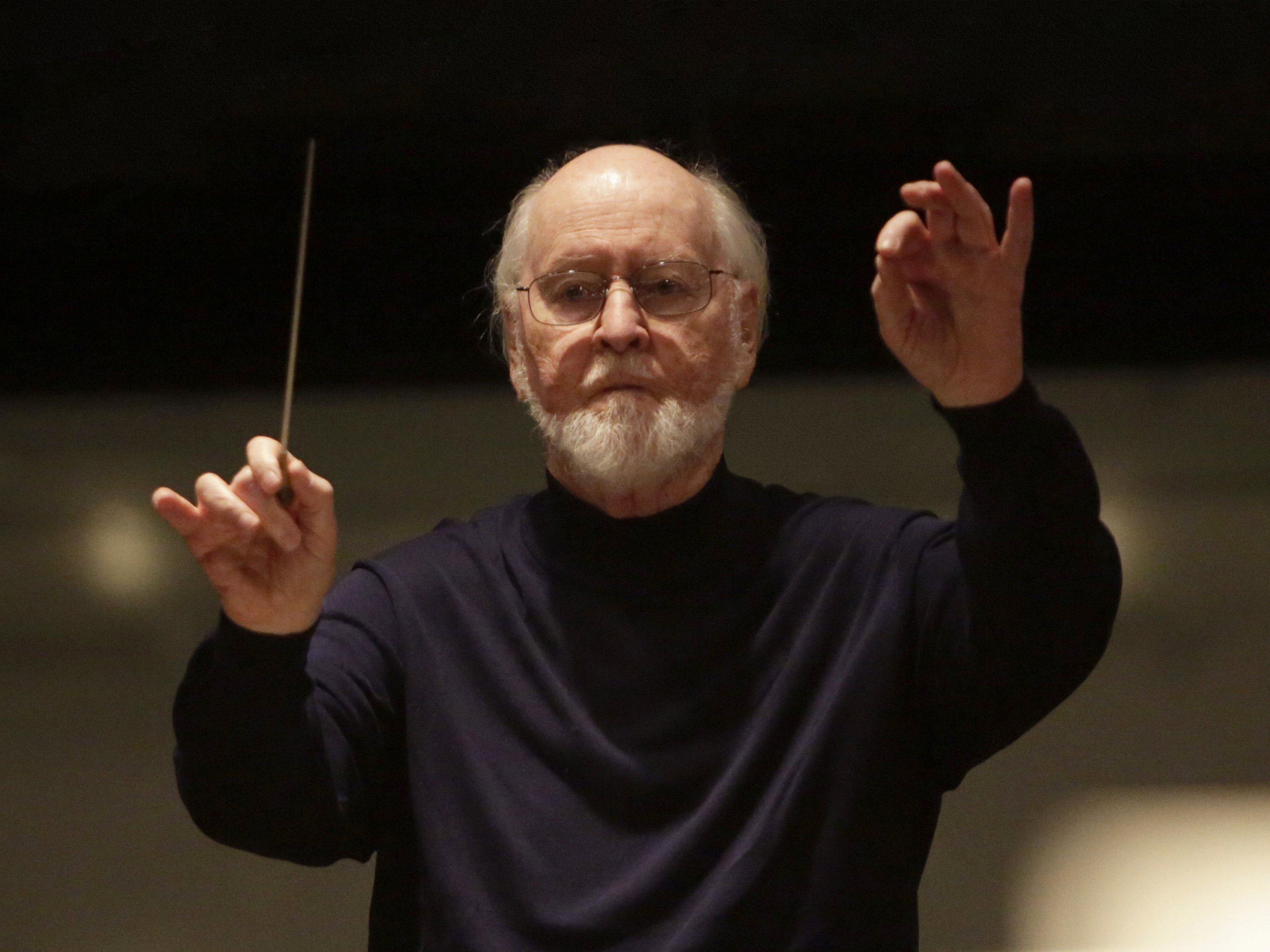

The symphonist of film

The history of film music would not be the same without him: John Williams.

“It’s never enough, it can never be too much”

The conductor and harpsichordist Emmanuelle Haïm is one of the leading protagonists of early music. Portrait of a baroque icon.