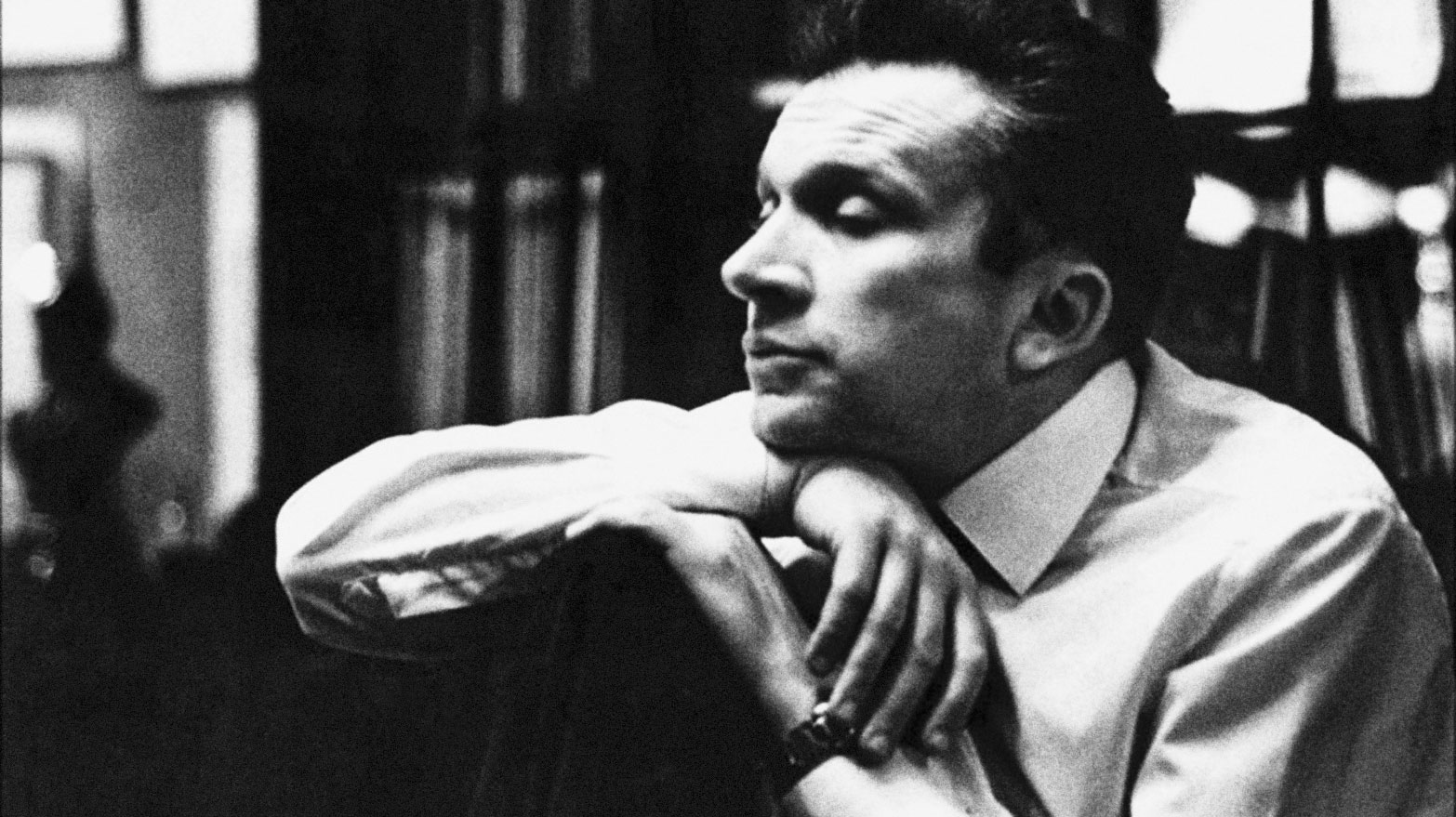

- Portrait

The British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams is considered one of the greatest symphonic composers of the 20th century. Nevertheless, his works are rarely on the repertoire of German concert halls. October 2022 marks the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth. Reason enough to dedicate a portrait to the all-rounder.

We need to begin by sweeping aside the prejudicial and defamatory belief that England is a “land without music” for such a view has no justification. In a spirit of defiance, mainland Europeans may of course object that the English have not produced great composers in any consistent and continuous way and that between Purcell and Elgar there is a striking gap in the English musical tradition. But in the interests of justice this genealogical shortcoming would also have to be taken into account in any discussion of the music of other countries.

It was Edward Elgar who broke this spell and dragged Great Britain out of the shadows of musical insignificance. The first performance of his Enigma Variations in 1899 is regarded by many as marking a fresh start in the history of English music or at least as signalling its rebirth. It was left to a younger generation of composers to continue a tradition that had begun with such promise. The times could not have been more favourable for Elgar’s heirs. The United Kingdom was in the grip of an unprecedented and feverish desire to build on Elgar’s achievements: new orchestras and concert halls attracted audiences in droves.

True collector and preserver of the Folk Song

But Ralph Vaughan Williams would undoubtedly have written his music under far less favourable conditions. Throughout all of the vicissitudes of fate that he endured, his salient characteristic remained his independence in terms of both his judgement and the goals that he set himself. Of course, he could literally afford to adopt this course because as the son of a family of leading lawyers and academics – his great-uncle was none other than Charles Darwin – he had no need to worry about money problems.

Between 1903, when as a still relatively unknown young composer he jotted down his first ideas for A Sea Symphony, and 1958, when the eighty-five-year-old master musician’s final symphony was premiered only a few months before his death, Vaughan Williams left his indelible mark on the British musical scene, latterly a grand old man who had come to be seen as an authority, even as an institution: an eloquent teacher, speaker, peripatetic lecturer and columnist – but above all a trail-brazing English symphonist worthy of standing alongside Elgar. He wrote nine symphonies in the course of his lifetime – a magical number around which legends have accrued, instilling superstitious fears in composers mindful of the fate of colleagues like Beethoven and Bruckner, who had lived only long enough to complete or even only to start a similar number of symphonies.

A self-styled individualist and an Englishman through and through, Vaughan Williams first had to develop his own art, and to achieve this end he needed to pass through many a school both at home and abroad. He studied with Hubert Parry in London, with Max Bruch in Berlin and with Maurice Ravel in Paris. He played the violin and the viola, founded a choir in Cambridge, worked as an organist at St Barnabas’s Church in South Lambeth in London. He also immersed himself in the mysteries of English vocal polyphony from the golden age of the Tudors.

Like Bartók and Kodály in Hungary, Vaughan Williams also undertook fieldtrips the length and breadth of Norfolk, Essex and Sussex in his search for the vanishing traditions of the English folk song. Possessed by the enthusiasm of the true collector, he listened to songs in situ, recorded them and published them systematically, resulting in the preservation of hundreds of songs: “I think we have a lesson to learn from the inventors of those folk songs,” Vaughan Williams was convinced.

“Why did the singers and inventors of folk songs sing them and invent them? It was not because they wanted to produce a novelty; it was not because they wanted to get up an entertainment to pay off the debt on the organ; and neither was it because there was going to be a festival and everyone was going to be there. The reason why those early musicians sang, played, invented and composed was simply and solely because they wanted to; and I think the lesson we can learn from them is that of sincerity.”

“On Wenlock Edge”: A prophetic song cycle?

Vaughan Williams was born on 12 October 1872, 150 years ago, at Down Ampney in Gloucestershire. Although his sesquicentenary has been barely noticed in Germany, the Berliner Philharmoniker are marking the occasion by performing On Wenlock Edge with two English musicians, the tenor Andrew Staples and the conductor Daniel Harding. This early masterpiece dates from 1909 and has not previously been performed by the orchestra. This collection of songs is impossible to pigeonhole, and yet it is precisely in this ambiguity that its charm and its fascination lie. At first sight it appears to comprise six songs or else it could be viewed as a cycle based on the contemporary collection of poems, A Shropshire Lad, by A. E. Housman. Shropshire is a county in central England, and Wenlock Edge is a limestone escarpment there. Housman, who held a chair in Latin in London and, later, in Cambridge, wrote these poems on the cusp of Romanticism and modernity, striking a note that is simultaneously sophisticated and folklike, hermetically sealed and yet intensely moving.

But the six songs that Vaughan Williams set – they were originally set for tenor, piano and string quartet and were orchestrated only much later – are far more than just a collection of folk songs in the nineteenth-century tradition. They revolve around the themes of young love and premature death (in one song Housman even adopts the daring trope of introducing a dialogue with a dead ploughman) and result in an extended monologue, the scenes of the surrounding countryside and the onomatopoeic and sometimes impressionistic playing of the ensemble serving as a mirror rather than as a depiction of the world around us.

The howling of the wind and the tolling of bells – everything is transformed into a quest undertaken by the human psyche as it seeks to enter a world of dreams and to penetrate the unconscious. But Vaughan Williams has taken his cue from the intonational patterns and dance rhythms of the English folk song and “invented folk songs” of his own, with the result that On Wenlock Edge already sounds familiar even in the ears of those listeners who may never have heard it before. There is a feeling of naturalness and even of friendship that speaks to us from these songs.

Everything here is interwoven and interlinked in the finest symphonic tradition, with the result that what Vaughan Williams wrote is tantamount to a symphony of songs that was almost exactly contemporary with Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, which represents a very similar hybrid form. The poems’ intimations of mortality, the melancholy of the music and the lament for young lives mown down before their time meant that on the eve of the First World War On Wenlock Edge also became a dirge and a farewell, a harbinger of things to come and a black and yet humane prophecy.

Vaughan Williams had learnt his lesson in sincerity: “The artist must not shut himself up and think about art, he must live with his fellows and make his art an expression of the whole life of the community – if we seek for art we shall not find it.”

And the Pain Remains Forever

The composer Mieczysław Weinberg is one of the great unknowns of the 20th century. A portrait

The Misfit

Anton Bruckner was always an outsider in Vienna’s polite society. Who was this “mifit” and what motivated him? In search of the evidence.

Clara Schumann and the Berliner Philharmoniker

Clara Schumann was a composer, a piano teacher and one of the most acclaimed pianists of her day.