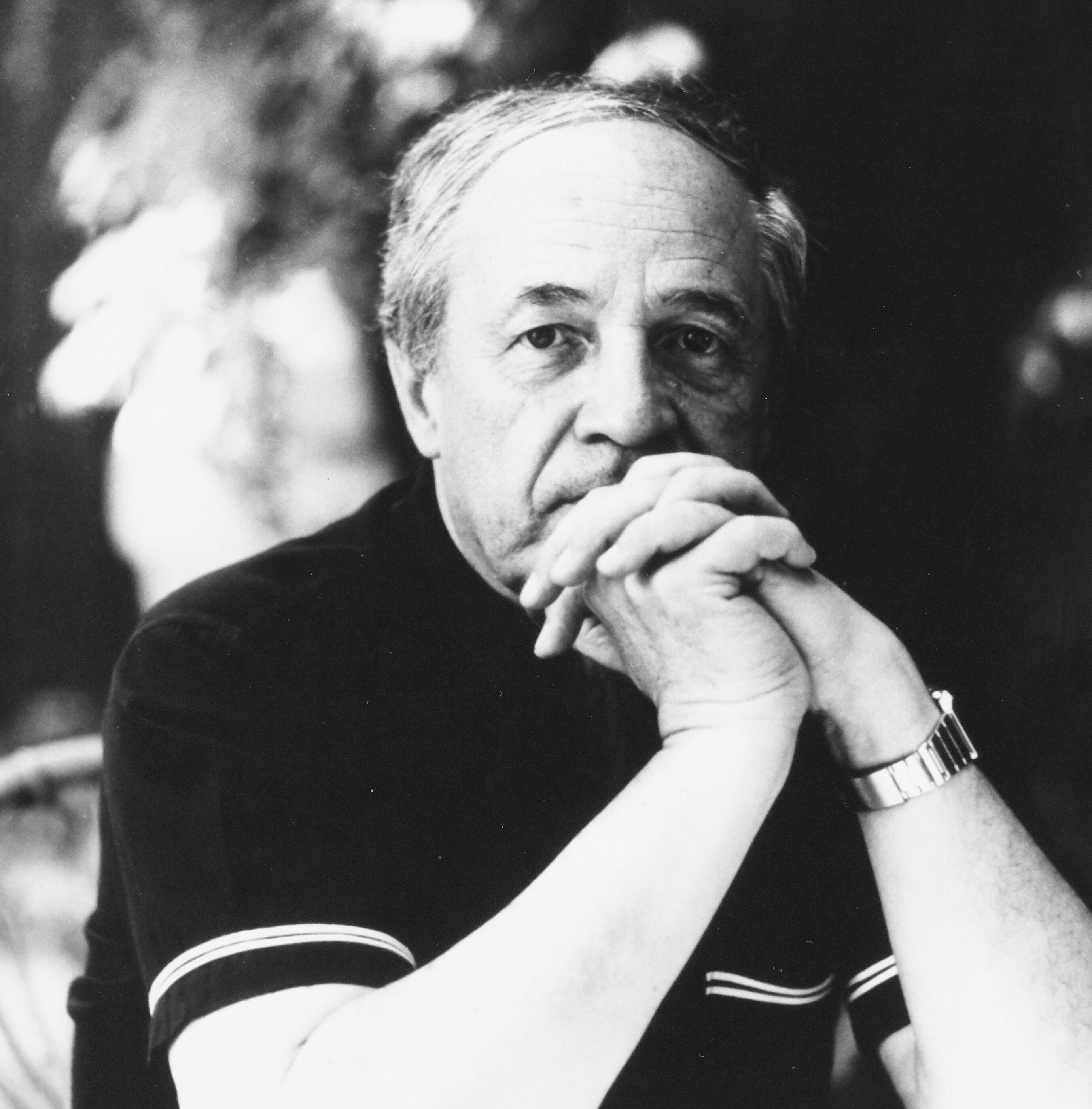

This year marks the centenary of the birth of Pierre Boulez. He was even more than a composer; he also left his mark on twentieth-century music as a conductor, a theoretician and a cultural politician. With the clarity of his vision, his analytical mind and his tireless urge for renewal, he embodied the musical avant-garde in ways that were altogether unique. Anyone who refused to conform to his idea of progress had to contend with harsh criticism.

Pierre Boulez as the Sun King: Werner Klüppelholz’s new book on Boulez is titled La musique, c’est moi!, an ironical paraphrase of Louis XIV’s “L’état, c’est moi!” To drive the point home, Boulez’s face is superimposed on the king’s iconic 1701 portrait. Boulez was not only an important composer. Born in the département of Loire to the west of Lyons, he became a towering figure in the world of music for half a century, not just as an eminent composer but also as a conductor, music theorist and arts manager. Anyone whom he condemned would find it hard to get ahead in the French music world. One of the composers who was made to feel Boulez’s fury in France was Henri Dutilleux, whose espousal of traditional values Boulez regarded as a personal affront. And although he revered his teacher, Olivier Messiaen, he none the less dismissed the latter’s Trois Petites Liturgies as “brothel music”.

In Germany, Boulez found a bête noire in the form of Hans Werner Henze. Their skirmishes dated back to the Donaueschingen Summer School of 1957, when Boulez left the concert hall demonstratively, along with Luigi Nono and Karlheinz Stockhausen, only a few bars into the world premiere of Henze’s Nachtstücke und Arien. The dispute later descended into absurdity. Interviewed for Der Spiegel in September 1967, Boulez claimed that Henze reminded him of a “barber with well-oiled hair”. Henze telegraphed back: “A tenant in the world of good taste, Boulez is a lonely Calvinist member of the petit bourgeois; he does not interest me. His polemics are those of a brewer’s drayman, and they get us nowhere.”

Boulez’s decision to make Henze his mortal enemy was based on two things – firstly, Henze’s continuing espousal of beauty as an aesthetic goal, and secondly, his use of traditional forms. Henze wrote not only symphonies but, even worse, operas. It is almost impossible to write about Boulez without mentioning his demand that all opera houses be abolished, a call which the subeditors of German news magazine Der Spiegel reduced to the pithy slogan “Blow up the opera houses”. The line stuck so hard that it resulted in his detention by the Swiss police decades later on suspicion of terrorism. In his infamous Spiegel interview, Boulez may have sounded waspish, but his analysis of the aesthetic and social fustiness of the world of opera was remorselessly direct: “The Paris Opéra is full of dust and shit – not to put too fine a point on it," he said. "Only tourists still go there, because the building is a must-see for them.”

Against dusty traditions and institutions

Boulez’s anger may have been justified in the pre-revolutionary climate of 1967, but since then a great deal has changed. Opera houses are more democratic, as are relationships between audiences and musicians. The fact that an “establishment” concert hall in Berlin bears Boulez's name can be attributed not only to the type of events held there – which include contemporary music, lectures and discussions – but also to the architecture of a space that consciously eschews all sense of hierarchical structures.

A year before his controversial interview with Der Spiegel, Boulez had conducted for the first time at the Bayreuth Festival. Wieland Wagner had coaxed him to the “Green Hill” for his own production of Parsifal. Even more momentous was his work on Patrice Chéreau’s centennial production of the Ring. When it opened in 1976, the performance was disrupted by protesters blowing dog whistles, but after the final revival in 1980, there was a standing ovation that lasted ninety minutes. Here, as always, Boulez rejected bombast and empty rhetoric to ensure that the score flowed freely, its textures fully translucent.

The Berliner Philharmoniker first engaged Boulez to conduct in 1961, when intendant Wolfgang Stresemann invited him to direct a programme that included his own Pli selon pli – Portrait de Mallarmé alongside works by Debussy and Webern. By this point in his career, Boulez, who spoke excellent German, had already set the tone at two of Germany’s leading centres for the musical avant-garde, Donaueschingen and Darmstadt. He had also relocated to Germany, moving into a villa in Baden-Baden. After a lengthy absence, he returned to the Berliner Philharmoniker in 1993, treating audiences to benchmark readings of twentieth-century classics.

By then, in addition to pursuing an international career as a conductor. Boulez had overseen the building of an innovative music institute and research centre in Paris, the Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique, or IRCAM. Located directly opposite the Centre Pompidou, it opened in 1977 as a laboratory of experimental sounds, where science, technology and artistic expertise still cross-pollinate today. Thanks to his political contacts, Boulez's vision of a new form of contemporary music had become reality.

Proliferation as a compositional principle

As a composer, Boulez drew on the resources at his disposal. It was thanks to the IRCAM systems, for example, that his …explosante-fixe…, inspired by Stravinsky, found its final form. Acoustic instruments and electronic components are combined in this work by means of a computer system that was revolutionary for its time, creating fascinating soundscapes.

Boulez was only twenty when he wrote Notations, a key work for the piano: this was an instrument with which he was closely associated, despite the fact that he failed the admission examinations to study piano in both Lyons and Paris. One of the performance markings in Notations is “incisif” (incisive). This would return later in his sometimes-aggressive and fragmented musical language. The piano is also granted an important role in a number of his chamber works; his Structures for two pianos is another key work.

The model for the young and inquisitive generation of post-war avant-garde composers was Webern. “A composer who has not recognized and understood Webern’s inescapable inevitability is absolutely useless,” Boulez declared categorically in 1961. Serial music had emerged from Webern’s concentrated vocabulary, from his supersession of gravitational tonality, and from the autonomy of his every note. Pitches are organized in rows, but it did not stop there; other parameters, such as length, volume and tone-colour, were serialised. Boulez, who had originally wanted to study mathematics, could use serial music to express his sense of proportion and his love of number games. But the term “proliferation” also came to characterise his style. “For me, a musical idea is like a seed," he explained. "You plant it in a particular type of soil, and suddenly it proliferates, like a weed. You then have to remove the weeds”. This formative principle also explains the succinct gestures of his music.

As both a thinker and a master builder, Boulez had a lasting impact on later generations, and a number of his students now hold prominent positions in today's music world. One of them is Ondřej Adámek. “If I had to sum up what Boulez meant for me," Adámek says, "it would be respect, clarity of mind, efficiency and encouragement”.

Revolutionary, visionary, universalist

On the 100th birthday of Pierre Boulez

Scandalous works in classical music history

Many of the works that now have a firm place for themselves in the international concert repertory have had to struggle to achieve that status. They sparked riots, provoked censorship and divided audiences.

Orchestra history

Discover more than 140 years of history of the Berliner Philharmoniker!