- Knowledge

- History

A tenor’s high C remains the non plus ultra of male singing. For centuries, tenors have been at the centre of the musical world: Enrico Caruso, Mario Del Monaco, Giuseppe Di Stefano and Franco Corelli were all fêted like rock stars. But this is about far more than mere vocal acrobatics, a point amply demonstrated by Benjamin Bernheim, the soloist of the Berliner Philharmoniker’s forthcoming New Year’s Eve Concert. We examine the myth of the tenor.

Naples, 19 August 1921. The whole world is in mourning; a great man has died. Hundreds and thousands of people line the streets, and the houses that line the funeral procession’s route are all draped in black. The king himself – Vittorio Emanuele III – has ordered the service to be held in the Church of San Francesco di Paola, which was usually reserved for royal occasions. The embalmed body is on view in a glass coffin. The handpicked congregation of mourners includes crowned heads of state, members of the moneyed classes, friends and colleagues. Flags are flying at half-mast throughout Italy. Shops in Naples are closed, and life has come to a standstill. Who has earned such a tribute? It is a tenor! Enrico Caruso has died at the age of only forty-eight.

In the beginning was Caruso

The media circus that still surrounds tenors began with Caruso. Of course, there would have been no excitement had he had not been gifted with a unique voice: tender and mellifluously lyrical, seductive, flexible and baritonal in colour. According to the German soprano Frieda Hempel, hearing Caruso’s voice was “like sinking into a deep, soft, comfortable velvet-covered armchair”. Caruso’s popularity was closely linked to the invention of the gramophone. In 1902, t the age of twenty-nine, he made the first of a total of some five hundred recordings. They sold like hot cakes, and within two years had already passed the two million mark. Caruso earned a fortune, and certainly knew how to market himself. He appeared no fewer than 863 times at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and reached mass audiences by performing in bullrings. Once, when he sang in Berlin, 30,000 people milled outside the opera house, hoping to glimpse him. He released information about himself extremely sparingly, in the process fuelling existing myths about him. What was the chemical composition of the mysterious mouthwashes that he invariably used immediately before his performances? And what about his nicotine intake of (allegedly) two packets of cigarettes a day?

Heirs and imitators

All the most famous Italian-repertoire tenors of subsequent generations tried to pick up where Caruso left off, modelling themselves on him vocally, stylistically and even through their marketing. Beniamino Gigli was initially seen as Caruso’s legitimate successor, although his strengths lay in the lyric repertoire. He was criticized for such ostensible failings as his interpolation of excessive sobs. Mario Del Monaco was undoubtedly better-looking than Caruso, so much so, indeed, that he appeared in several films. His top notes also had a more metallic ring and a remarkable sheen to them, but he was never able to compete with his predecessor in terms of his actual timbre. Giuseppe Di Stefano owed his reputation not least to his inspired partnership with Maria Callas. And Franco Corelli may have started his career with a magnificent voice, but all too soon he took on roles that were too heavy for him, to say nothing of his constant battle with stage fright. Plácido Domingo, Luciano Pavarotti and José Carreras were all better at marketing themselves than Caruso had been, more especially when, towards the end of their careers, they joined forces as the Three Tenors and filled entire football stadiums. Their idea has now been imitated by tenors who have come together in even greater numbers, but the aggregate seems to diminish them; do tenors come more cheaply by the dozen?

Where did the myth originate?

So why were tenor heroes destined to create this myth? Why are there not Five Basses or Seven Mezzos or Four Sopranos? In fact, the hype surrounding tenors is a relatively recent phenomenon. The tenor voice came to prominence with the rise of polyphony in the thirteenth century, when tenors sang the cantus firmus (literally, the “fixed melody”), the main melodic line, which was made up of sustained notes. The noun tenor derives from the Latin verb tenēre, meaning “to sustain”. The countermelody that wound its way round the tenor line was then known as the contratenor and was normally higher than the tenor. It was this higher line that became the most popular one in Italian Baroque opera: the main roles were sung by castratos, who were also capable of singing notes normally reserved for sopranos. Throughout this period, tenors were limited to secondary roles that were regarded as less spectacular.

The situation in France was very different. Here composers such as Lully, Marc-Antoine Charpentier and Rameau wrote their heroic roles for the tenor voice, albeit the specifically French type of voice known as a haute-contre. Although the writing for this kind of voice often extended above c'', two octaves above middle c, these notes would never have been belted out, but were instead sung using the head voice, or falsetto. This tradition continued in French opera well into the nineteenth century. Perhaps the most famous example is Don José’s Flower Song from Carmen, which Benjamin Bernheim sings at the New Year’s Eve Concert in Berlin. At the end of the aria, Don José, who is hopelessly in love with Carmen, has to ascend to a high b♭, which he must sustain for what seems like an eternity, performing it, according to the instructions in the score, pianissimo and con amore, in the process investing the note with a sense of profound entreaty.

If we take this performance marking literally, then the note must be sung falsetto, or using a voix mixte, a subtle combination of head voice and chest-voice. Despite this, it has become common in recent decades to sing this much-feared top note full out, fortissimo, using only chest voice.

A new tenorial ideal

The great change took place in the 1830s, and we owe it to the French tenor Gilbert Duprez. He is believed to be the first singer to use full chest- oice for a high c'' that occurs in Arnold’s role in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell in order to create a dramatic effect. Rossini himself was unenthusiastic about this innovation, complaining about Duprez “assaulting the ears of his Paris audience with his ut de poitrine, which had never been my intention”. Rossini even compared the sound to that of a capon having its throat cut. Whether he intended to or not, Duprez laid the foundations for a new tenorial ideal that was no longer gentle and lyrical, but rather manly, heroic and potent: testosterone in music. The myth of the tenor was born.

Composers like Verdi and Puccini were quick to take advantage of this development, and from now on wrote their high notes for the tenor’s chest register. Wagner, of course, was determined to outdo them all. His tenor hero Siegfried requires ironclad lungs for his Forging Songs in the music drama that bears his name, and has to ensure that his voice can carry over a gigantic orchestra. This recalls the Greek hero Stentor in Homer’s Iliad, whose voice was said to have been as loud as those of fifty men. Who can hope to beat this?

Volume and power seem to be an inevitable part of the cult of the modern tenor. But not all tenors are the same. There is a world of difference between the Evangelist in Bach’s Passions, where the singer must use his light tenor voice to declaim the Biblical narrative, and Wagner’s Tristan, who for five hours has to pour his vocal resources into some of the most challenging writing in the whole of the operatic repertoire. The range of voice types also includes the buffo tenor, the lyrical Mozart tenor, the tenore di grazia of the bel canto tradition, the tenore spinto favoured by Verdi and Puccini, the character tenor and the heldentenor of the German repertoire. Phenotypically, too, the differences outweigh the similarities. And tenor voices change over time: Jonas Kaufmann, for example, began as a Mozart tenor and worked his way up through the Italian repertoire before taking on the heaviest of heroic roles.

“Bel canto is like Pilates”

Among today’s most acclaimed successors to the great Caruso is Swiss-French tenor Benjamin Bernheim, a true intellectual within his field. He regards the tenor voice as something “unnatural” and is well aware that no master simply falls from the sky. Bernheim offers this piece of advice to his fellow singers: Never devote yourself exclusively to dramatic repertoire – alternate between different vocal categories instead! For this reason, he himself regularly returns to the works of Rossini, Donizetti and others: “For me, belcanto is like Pilates: the voice is guided with great delicacy, using small, controlled movements – training the instrument in a healthy way.”

And what should a good tenor have to bring to the table? Enrico Caruso once summed it up succinctly: “A big chest, a big mouth, 90 percent memory, 10 percent intelligence, lots of hard work and something in the heart.”

Wagner’s female characters

Siegfried, Wotan and Tannhäuser: it is the male heroes who seem to leave their mark on Wagner’s music dramas. But closer inspection reveals that it is the female characters who guide events, through their resolute actions and farsightedness

A scherzo with a fatal conclusion

Richard Strauss’ opera Salome bears a reputation for scandal (even today). No wonder, as it was censored at times and the soprano at the premiere initially refused to take part.

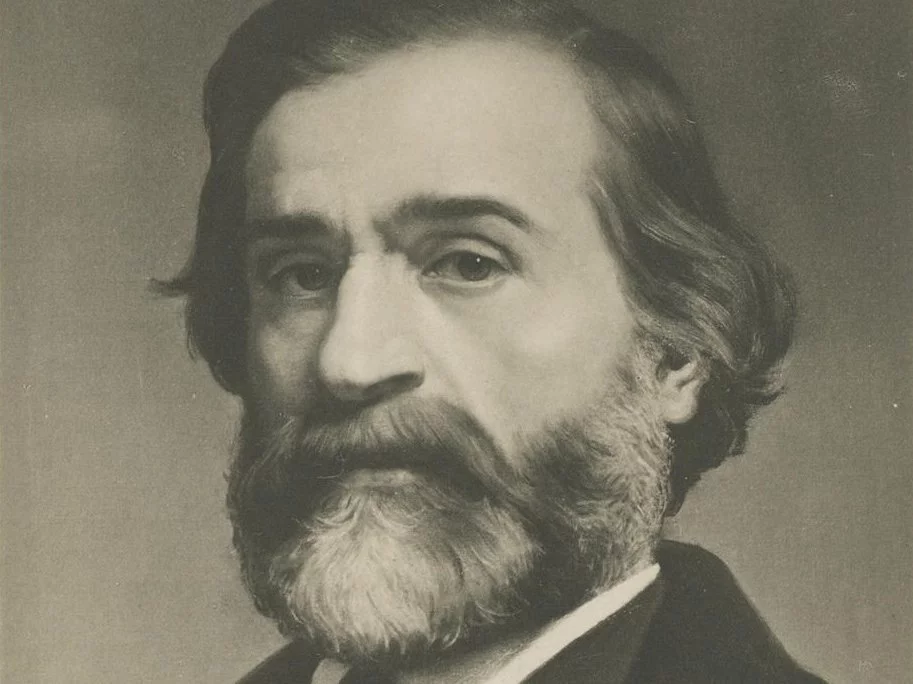

9 Facts you (perhaps) didn't know about Verdi

You can hum along to “La donna è mobile” in your sleep, but did you know that Verdi was a vintner, a member of parliament and a keen foodie?