- History

They could not have been more different: he, the son of a Jewish cantor from Dessau with a sheltered upbringing, a pupil of the famous Ferruccio Busoni, highly gifted, and well aware of his genius; she, the daughter of a washerwoman and a hackney carriage driver from Vienna. Neglected and beaten by her alcoholic father, she did not attend school and at times turned to prostitution. Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya came from worlds that never actually crossed. The fact that the two nevertheless met was – as so often in life – a happy coincidence.

Dream destination Berlin

In 1913, at the age of 15, Karoline Wilhelmine Charlotte Blamauer, as she was named at birth, fled from her family misery to Zurich, where she tried her hand as a dancer and actress. Eight years later, she came to Berlin. Although the young Weimar Republic was in a permanent crisis both economically and politically, the German imperial capital was considered the place to be artistically. Berlin was a kind of experimental laboratory where a new art, new forms of expression and new sensibilities were being developed.

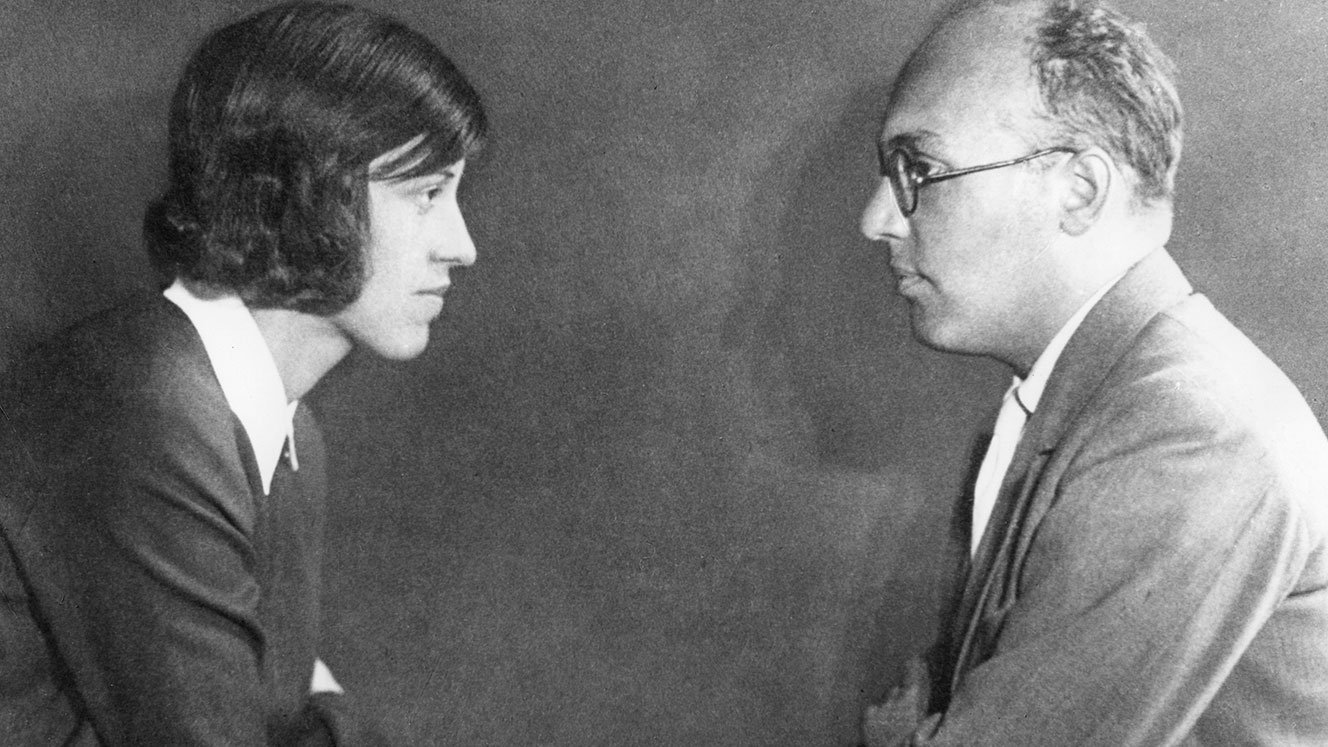

During this time Lotte Lenya, as she now called herself, met the Expressionist playwright Georg Kaiser and his wife Margarethe. They became friends and Lotte regularly visited the Kaisers at their home in Grünheide near Berlin. Lotte Lenya recalled a Sunday in the summer of 1924 when Kaiser asked her to pick up a musician at the station: “ʻHow will I recognise this gentleman?ʼ and Kaiser said: ʻOh, that’s quite easy; composers all look alikeʼ. It was a small, deserted station – especially on Sunday mornings there wasn’t a soul there. But there was a little man standing there with a hat typical of a musician on his head and thick glasses.” The guest was Kurt Weill, and the meeting on the platform was the beginning of a passionate relationship that would last until Weill’s death in the spring of 1950.

An unconventional marriage

It wasn’t long before Lotte Lenya moved in with Kurt Weill in his tiny flat on Berlin’s Luisenplatz, and they married at the end of January 1926, much to the dismay of Weill’s pious parents. “She’s a terrible housewife. But a very good actress,” quipped the husband. “She can’t read music, but when she sings, people listen like they did with Caruso. (Incidentally, I feel sorry for any composer whose wife can read music).” Although Lotte indeed lacked any musical training, thanks to her keen artistic sense she became Weill’s closest advisor and, over time, his most famous interpreter.

He wrote five roles for her. For generations, her deep, smoky voice defined the ideal Jenny from the Threepenny Opera and the Jenny from the Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Neither of them was very particular about marital fidelity. Lotte’s affairs were as numerous as they were casual. They didn’t mean much to her, merely amusements and erotic diversions. “Kurt didn’t have many affairs,” she later recalled. Once he fell for the wife of a friend. Lotte took it calmly: “She was a little sex kitten, one of those coarsely funny blondes. I can well imagine why he fell for someone like that.” Nevertheless, Kurt and Lotte’s marriage broke up in 1932 – for a time. They divorced, only to marry again in 1937.

Divorced and remarried

At that time, they had already been living for two years in the United States, where they had fled from the Nazis. In 1941, they bought a house in New City, New York State, which became the centre of their lives. In the new world, Lotte occasionally performed in New York nightclubs singing Kurt’s songs or toured all over with a theatre company, whereas he regularly spent many weeks in California. When they couldn’t see each other, they wrote each other adorable letters full of poetry and flippant comments, gossip, erotic indiscretions and artistic news. Neither of them minced their words. “Yesterday afternoon I dropped by the Gershwins,” Kurt let her know in May 1937.

“They live in a palace, with a swimming pool and a tennis court. But George has become even dumber than he already was. They were very nice to me.” Weill was mostly uncomfortable with social contact with other emigrants. If a meeting could not be avoided, he usually stayed only briefly and sent his “darling”, as he called Lotte, a detailed report the next day. “Last night I had to go to Slezak’s dinner party,” he grumbled in August 1944. “It was one of the worst meetings of refugees I have ever had to endure. A German-language evening of the worst kind – because it wasn’t even German, but this vile Hungarian-Viennese mixture. The Werfels were very nice. He’s ill and she’s an old fool, but oddly warm and cordial to me and honestly delighted with Lady in the Dark, which she’s seen twice. Walter Reisch dominated the conversations. He should be shot right after Hitler.”

From Russia with love

When Kurt Weill died of a heart attack in early April 1950, Lotte Lenya was devastated. She withdrew from the public eye and watched over her late husband's work with uncompromising strictness. But friends persuaded her to return to the stage and Lotte played Jenny on Broadway with as much success as she had in Berlin in the late 1920s. In 1961, she received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Contessa Magda Terribili-Gonzales in The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone.

Two years later, she played the fearsome secret agent Rosa Klebb in the James Bond film From Russia with Love. Lotte Lenya married two more times – and survived these men as well. In 1979, two years before her death, she drew a thoughtful balance of her life with Kurt Weill: “Nobody really knew him very well. I have often wondered if I knew him. I was married to him for 24 years, and before we were married we lived together for two years, so 26 years in total. But when I had to watch him die, I doubted whether I ever knew him.”