- Orchestra History

One year ago, the Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings label attracted considerable attention with a special edition. Thanks to previously-unreleased broadcast recordings, listeners were able to immerse themselves in the 1950s and 60s, revisiting the early years of the Karajan era with the Berliner Philharmoniker. Now the second instalment has been released; an opportunity to look back at the collaboration between conductor and orchestra in the 1970s.

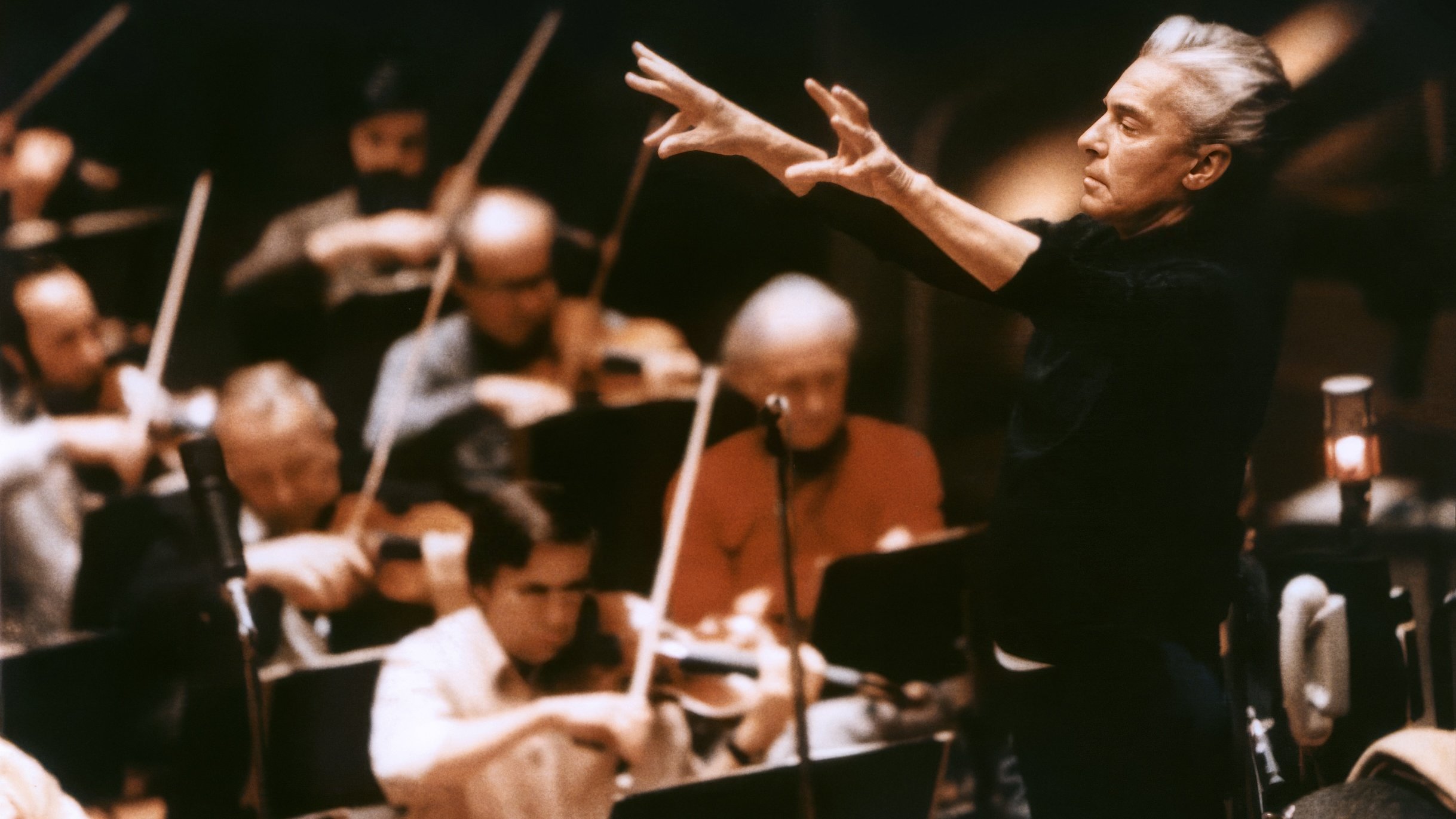

The 1970s represent a golden middle in the Berliner Philharmoniker's Karajan era. The orchestra and its chief conductor were making music at the absolute peak of their powers, and the unmistakable sound that defined their collaboration reached its apotheosis. In comparison with earlier interpretations, the initial impression is of greater homogeneity and radiance in the orchestral sound. But there’s more to it: this is music-making in which each note is moulded and supports an overall conception of sound and drama. Yet a wealth of nuances refute the common allegation of uniformity.

Reaching that level required tireless work on the great symphonic repertoire. When Simon Rattle met Karajan in the mid-80s, the latter surprised his younger colleague with the observation: you can, he said, just “throw away your first 100 Beethoven Fifths”. He meant that only partly in jest. In fact, Karajan performed the symphony with the Berliner Philharmoniker 104 times over the course of his life, not counting studio recordings.

In rehearsal, his concentration on a single articulation or tonal colouring could be intense. In concert, on the other hand, it was important to Karajan not to constrain the orchestra with too many specific demands. He explained it in terms of riding: “When you want to jump a fence,” he said, “you don’t carry the horse; the horse has to carry you.” He approached his musicians the same way: he guided them into position – they had to jump. An important role was played by Karajan’s habit of conducting concerts with his eyes closed, whereas in rehearsal he communicated with his musicians by direct eye contact. Alexander Wedow, a cellist in the orchestra from 1962, recalls that while this lack of contact in the concert could be disconcerting, “on the other hand, it gave us an incredible freedom. Karajan let us off the leash.”

Media communicated this extraordinary collective music-making to a global audience. In 1970, Karajan entered into an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon, which foresaw a massive volume of releases with the Berliner Philharmoniker, encompassing works from Vivaldi to Strauss, from Schumann to Schoenberg. He also proceeded with a project begun in the 1960s: the audiovisual recording of core concert repertoire such as the symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms and Tchaikovsky.

As much as they were aligned in matters of music and business, personal contact between the conductor and his musicians remained distant. Karajan did say in 1974 that through their work together, the Berliner Philharmoniker and he “had become a family”, but he was referring to closeness in artistic matters. Some musicians relate that during their entire time in the orchestra they never once spoke directly with their chief conductor. Rudolf Watzel, who was in the Philharmoniker’s double bass section from 1968, recounts: “I played for 21 years under Karajan, and I’m certain he didn’t know my name. The distance between the maestro and the orchestra was simply a lot greater than in later times.” Then again, it is reported that Karajan cared attentively for orchestra members who were unwell, and helped them find a suitable physician. When a cellist’s mother waited in vain for a heart operation, Karajan resolved the issue by intervening personally at the German Heart Centre in Munich.

Trailer: Karajan-Edition

Karajan revealed his empathetic side during the 1970s principally through his engagement on behalf of the new generation of musicians. From 1969, he held a regular conducting competition; its most famous prizewinner was Mariss Jansons in 1971. He was also an advocate for Claudio Abbado, Riccardo Muti and, especially, Seiji Ozawa. Karajan was probably driven by memories of his own career. In younger years he had wished for a mentor, but instead had to contend with Wilhelm Furtwängler’s efforts to hinder his rise. He saw himself on the side of young talent – and thus of music’s future.

His most sustained endeavour in support of young players has been the Orchestral Academy he founded in 1972. The idea behind it was both new and compelling: conservatories prepare students for a solo career, but playing as part of a top-flight orchestra demands other qualities as well. These are imparted to the Academists by members of the Berliner Philharmoniker, augmented by regular participation in the orchestra’s concerts. In this way, the Academy – renamed the Karajan Academy in 2017 – also helps to preserve the Berliner Philharmoniker’s specific music-making characteristics across generations.

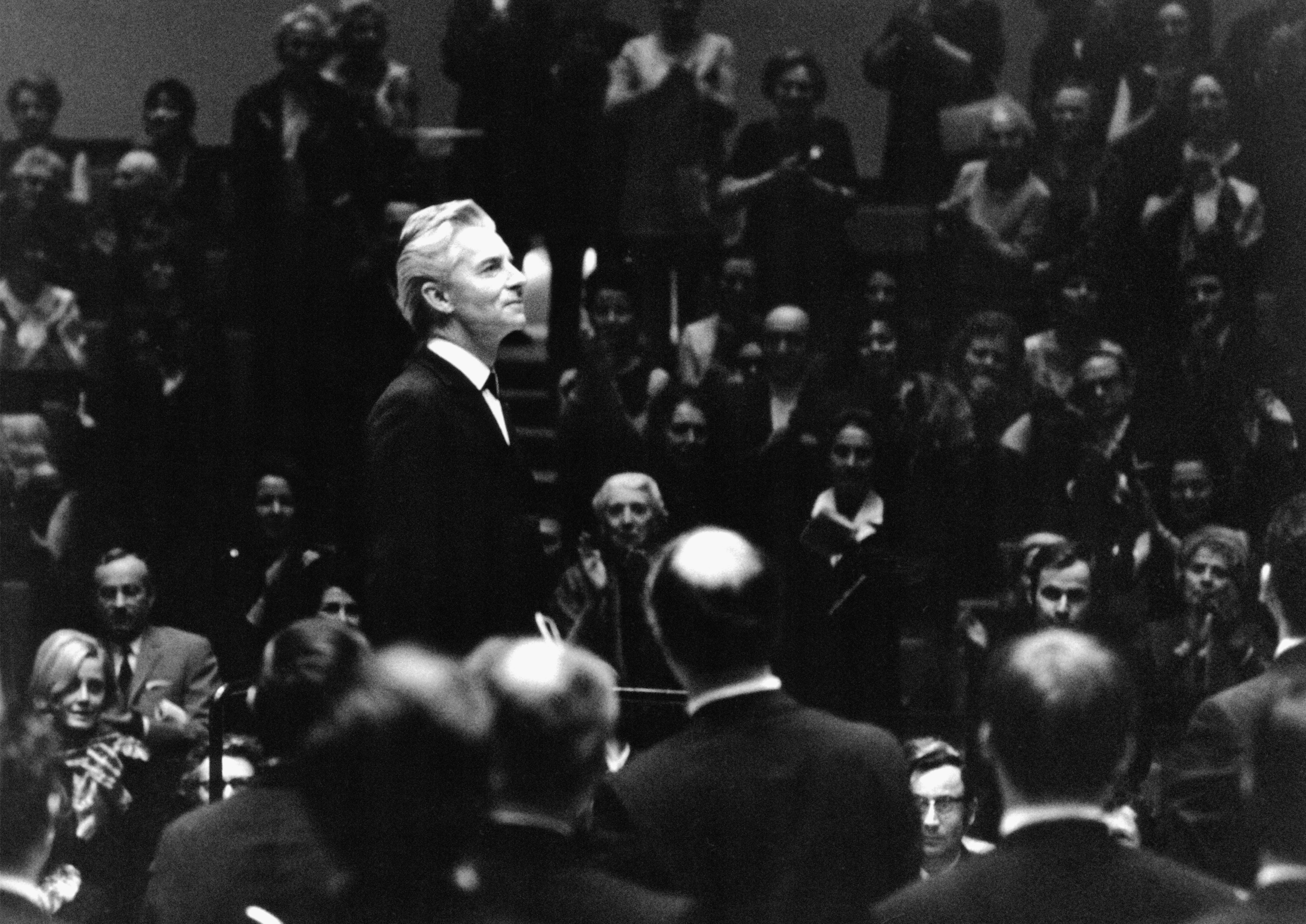

We may safely presume that Herbert von Karajan experienced the 1970s with the Berliner Philharmoniker as a highly rewarding period. He was able to realize not only his musical visions but also his media and education projects, and his authority as a conductor was uncontested both in public and within the orchestra. In 1973, he became the only chief conductor of the Berliner Philharmoniker ever to be made an honorary citizen of Berlin.

This text is a shortened version of an article from the accompanying book to the edition The Berliner Philharmoniker and Herbert von Karajan: 1970–1979 live in Berlin.

Karajan Edition (1953–1969 )

Experience Herbert von Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker live in Berlin between 1953 and 1969.

Herbert von Karajan: Sound aesthete and media star

Karajan, chief conductor from 1956-1989, embodied the conductor type of the 20th century: energetic, charismatic, visionary.

Filmstar Karajan

Herbert von Karajan erkannte früh die Kraft des Fernsehens für die Klassik. Georg Wübboldts Film zeigt, wie er das Medium prägte und seine Ästhetik schuf.