Forty years ago two groups of committed chamber musicians who were all members of the Berliner Philharmoniker formed an ensemble with the aim of performing Schubert’s Octet. So far, so good. What began as a bold experiment has developed over the intervening years into a major success story. Over the course of the last four decades, the Scharoun Ensemble – named after the architect of the Berlin Philharmonie – has become one of the leading chamber ensembles in Germany, its unusual forces opening up more and more new worlds of sound. From the outset its members have been able to forge a link between tradition and modernism while working with some of the world’s most distinguished conductors and composers. The ensemble’s fortieth anniversary is an opportunity to review its past.

What are the salient qualities of the finest orchestral musicians? Their aim is not only to perform the major symphonic masterpieces, they also feel the urge to explore small-scale forms. Barely have they closed their copies of the scores of Bruckner, Mahler and Richard Strauss than they are already thinking of the exciting pieces that they could discover with their closest friends and of doing so, moreover, in an intimate space that encourages the most intensive exchange of ideas.

In larger groups there needs to be a leader, someone who decides on the direction that everyone else must take. Chamber music, on the other hand, can be a living, breathing form of democracy since what matters here above all is to listen as closely as possible, to pay attention to what the other voices are saying, to pick up themes, think them through to their logical conclusion and hone one’s own powers of argumentation. Arguing passionately during rehearsals? By all means, but only over the matter in hand. After all, the goal is the best possible interpretation and the profoundest understanding of the work in question.

Happy Birthday Scharoun Ensemble

When the Scharoun Ensemble emerged from the ranks of the Berliner Philharmonic in 1983, Peter Riegelbauer was just twenty-seven years old. He had completed his studies three years earlier and had immediately won a place for himself at the orchestra’s Karajan Academy. By 1981 he was a member of the double bass section of the main orchestra, and however stressful and nerve-racking his first years as a newcomer may have been, he none the less felt the urge to perform chamber music with the few other young people who were members of the orchestra at that time.

Looking back on these early years, Peter Riegelbauer has nothing but respect for the “Philharmonic spirit” that reigned among this band of brothers and for the sense of pride felt by these mature, but by no means sclerotic, men, some of whom had played under Furtwängler. Despite this, there was a certain distance separating the older members of the orchestra from those who had only recently joined its ranks. The latter group included the horn player Stefan de Leval Jezierski and, among the violinists, Alessandro Cappone, who had joined the orchestra shortly before Riegelbauer, and Madeleine Carruzzo, who was the first woman to have auditioned successfully for the orchestra. Eight of them decided to form their own chamber ensemble since the first work that they wanted to perform together was Schubert’s wonderful Octet, with its unusual scoring for clarinet, bassoon, horn, two violins, viola, cello and double bass.

Chamber music as a living, breathing form of democracy

Peter Riegelbauer already had experience of new organizations since he had been present when the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie had been formed from members of the Federal Youth Orchestra. He was also one of those courageous souls who as members of the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie had founded Ensemble Modern in 1980 in order to play the latest music and try out entirely new working methods that were free from all hierarchical constraints.

For Riegelbauer it went without saying that he would want to establish a freely structured ensemble with his new musical friends, an ensemble tied to the orchestra but free in terms of its programming. The only question was what the members of this new Berlin-based chamber ensemble should call themselves. It was Elmar Weingarten, the orchestra’s later intendant, who provided the initial spark: “Name yourselves after Hans Scharoun!” Scharoun was the architect who had designed the Philharmonie and whose forward-looking ideas proved seminal when it came to building other concert halls. And yet his visions were never developed in a vacuum but were inspired by his knowledge of the historical legacy in question. This was entirely in keeping with the spirit of the new ensemble, which wished to remain open to all conceptual developments and which at the same time was inquisitive about both the past and the present.

Elmar Weingarten was not only the Scharoun Ensemble’s godfather, he also found the ideal venue for its debut concert in 1983: the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, the avant-garde exposed concrete building on the Lentzeallee near the Breitenbachplatz, a Scharoun-inspired building designed in the early seventies by Hermann Fehling and Daniel Gogel. The fact that the 130th anniversary of Scharoun’s birth falls a week before the concert marking the fortieth-jubilee celebrations commemorating the foundation of the Scharoun Ensemble that is taking place in the Philharmonie in Berlin that Scharoun himself designed is a wonderful stroke of serendipitous good fortune.

From a marketing point of view it would undoubtedly have been more sensible to have chosen a name that included the key word “Philharmonic” in order to make it clear where the musicians were coming from. But the project was never conceived along commercial lines. All that mattered was a serious engagement with the works that were being performed. The violoncellist Richard Duven set particularly high standards when he joined the Scharoun Ensemble in 1987, soon assuming responsibility for organizing the dates of the rehearsals and invariably planning more than the other players thought necessary. But the perfectionist was to be proved right, and the results of their intensive work were so outstanding that concert promoters all over the world were soon vying with one another to book the players. In addition to their activities in Berlin, which often included benefit performances for organizations like Greenpeace or for the peace movement, the Scharoun Ensemble was soon undertaking tours to the remotest corners of the earth. They travelled to Russia before the fall of the Iron Curtain and also went to China and visited Japan and the United States of America on repeated occasions. Among the experiences that have given its members particular pleasure have been the ten years that they spent as resident ensemble at the American Academy in Rome and the summer courses with Polish and German students at the Penderecki Music Centre in Lusławice.

The Scharoun Ensemble strives for nothing less than perfection

Among the great conductors who have worked with the Scharoun Ensemble are Claudio Abbado, Daniel Barenboim and Sir Simon Rattle, not to mention the wonderful friendship with Loriot, who has performed Saint-Saëns’s Carnival of the Animals more than forty times with them. Another constant in their repertory has been Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale, an exceptional piece of music theatre that they have given since 1988 with such varied artists as Udo Samel, Otto Sander, Fanny Ardant, Michael König and Dominique Horwitz. They have even founded their own festival and since 2004 have spent the first two weeks of September in Zermatt, working intensively with forty young professional musicians. Cut off from the rest of the world in one of the most beautiful parts of Switzerland, they can rehearse and perform here in highly concentrated ways.

Among the Scharoun Ensemble’s happiest moments Peter Riegelbauer recalls working with a number of living composers: among members of the older generation who are no longer with us are Hans Werner Henze, Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, György Ligeti and Isang Yun, while a younger generation is represented by Frank Michael Beyer, Matthias Pintscher, Thomas Adès, Olga Neuwirth, Andrew Norman and Jörg Widmann. “In close personal contact with the composer and working in detail on the music at the rehearsals, we find that these works are revealed to us in a completely different way than if we were merely to study the score,” Riegelbauer’s enthusiasm is palpable.

And then there is Brett Dean, of course, the multitalented Australian who joined the orchestra as a viola player, soon becoming a member of the Scharoun Ensemble and providing the players with witty arrangements for their unusual resources, notably the Overture to Johann Strauß’s Die Fledermaus, before starting to write music of his own. Much to his colleagues’ regret he left both the orchestra and the Scharoun Ensemble in 1999 and returned to his native Australia to focus on composing. But his friendly contacts with Berlin remained intact, and it goes without saying that for their jubilee concert he has sent the Scharoun Ensemble a brand-new score from the other side of the world. The gala programme on 27 September will also feature Schubert’s Octet – an inevitable choice in the circumstances – as well as Henze’s Quattro Fantasie and a new piece by David Philip Hefti. Taken together, these works provide an ideal conspectus of the ensemble’s unique versatility.

Fifty years of the Karajan Academy

A success story: the Karajan Academy has been training young orchestral talent since 1972.

Orchestra history

Discover more than 140 years of history of the Berliner Philharmoniker!

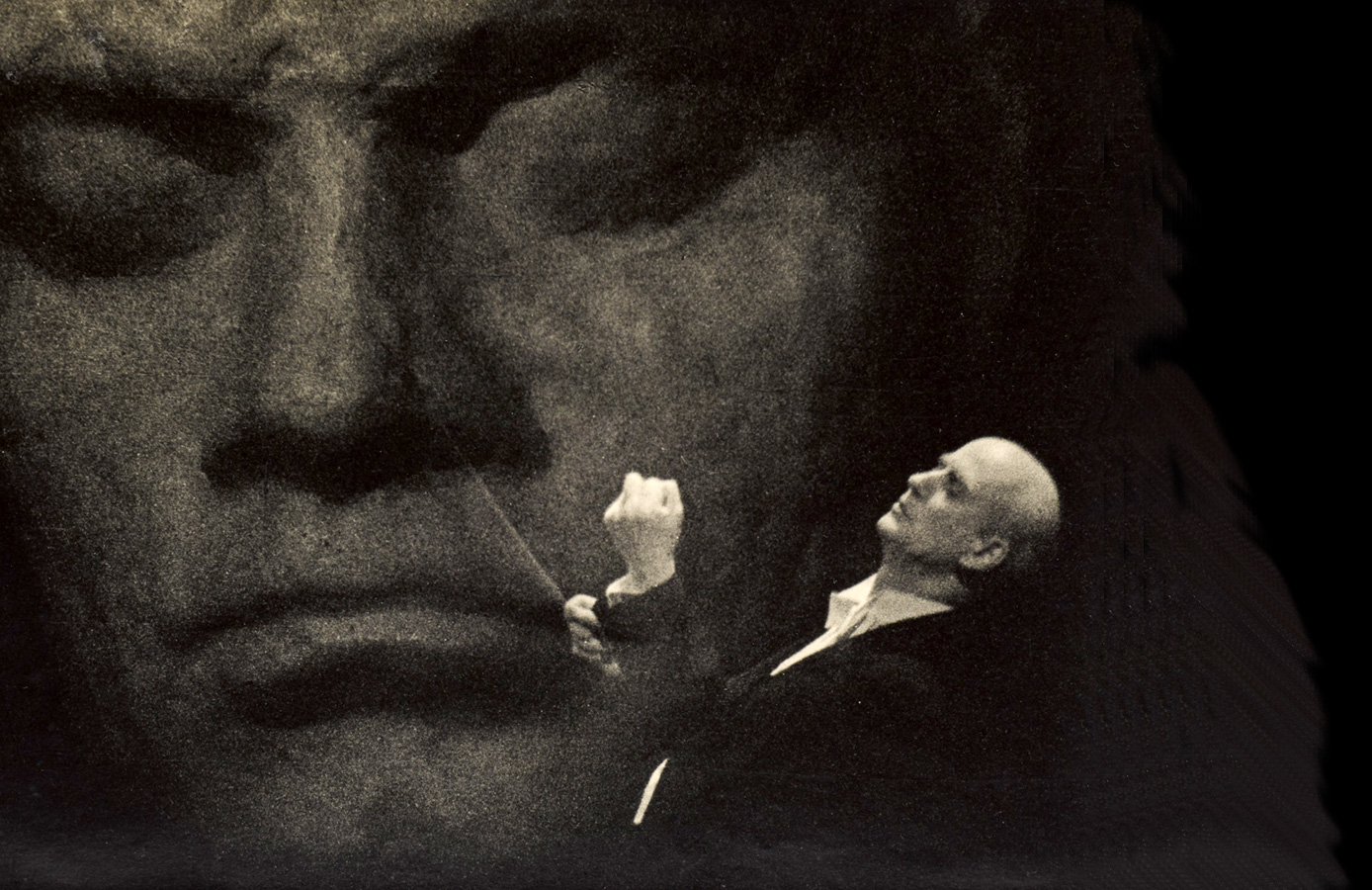

The Myth of the Chief Conductor

The Increase and Shift in Importance of the Conductor and Chief Conductor