What quarrels and fights there were, what journalistic wrangling before finally, on 28 October 1987, the opening fanfare was sounded. And how, later, the controversy was kept alive by Edgar Wisniewski, the architect of the Chamber Music Hall.

And he did so aggressively, like a man who has been wronged, you might say. Edgar Wisniewski (1930-2007) criticized the supposed cultural hostility of the politicians in Berlin as well as his own fellow architects with as much vehemence as he advocated his own ideas and goals which he constantly put forward in the name of his architectural mentor and later partner Hans Scharoun. The fact that the Chamber Music Hall was not built within a short time of the Philharmonie being completed in the 1960s was something Wisniewski regarded as an affront by the Berliners to musical culture. In any case, during the 1970s he tirelessly organised benefit concerts and, with significant support from the “Society of Friends of the Philharmonie”, collected a considerable amount of donations for the building; but to no avail. Only in 1983/84 did the mayor of Berlin, Richard von Weizsäcker, finally give the green light for the chamber music extension to the Philharmonie as part of the plans for the 750th anniversary of the city in 1987.

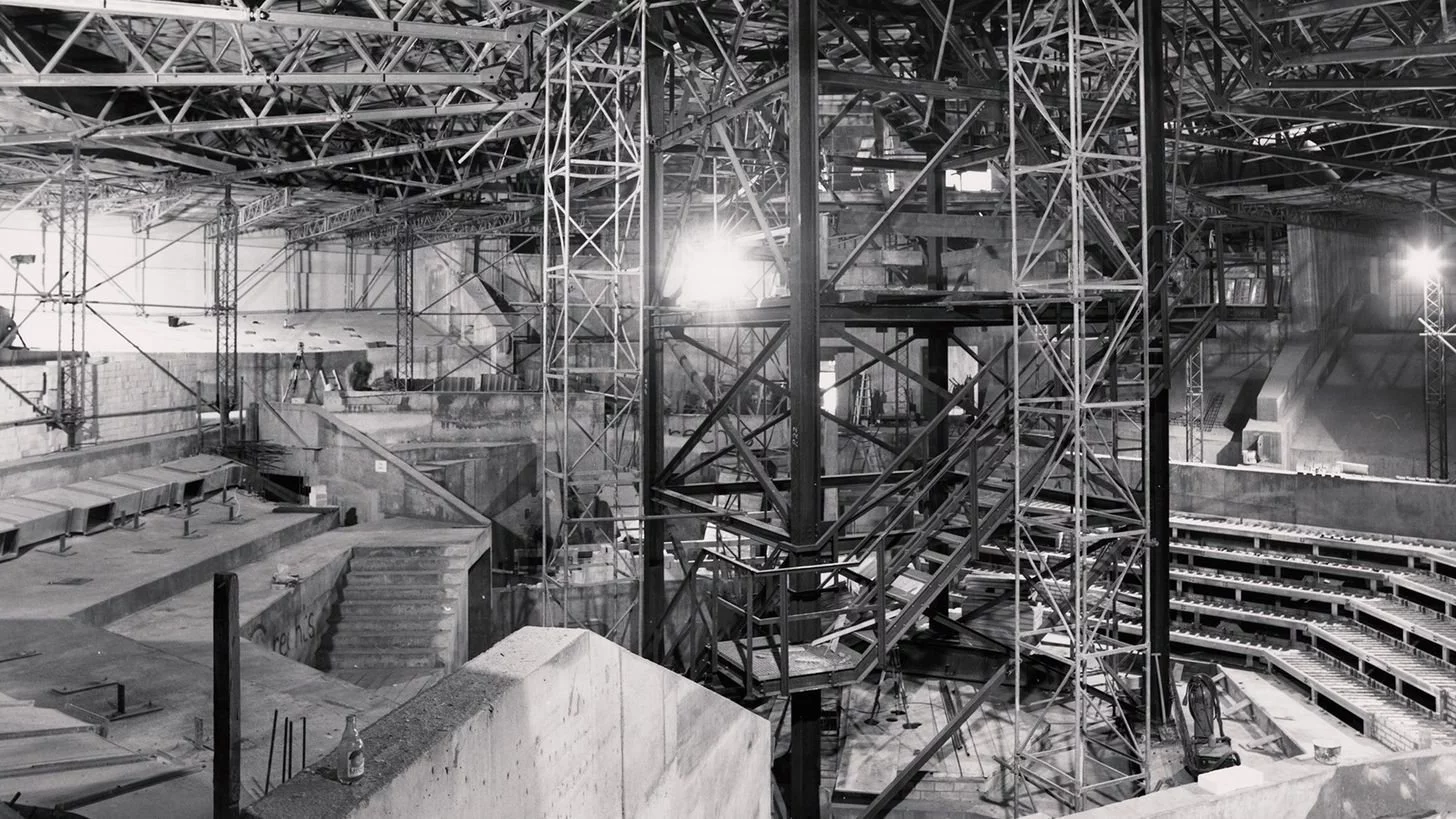

Grand opening after long planning and construction period

At the opening of the Chamber Music Hall, a chamber music festival was held on a scale the likes of which has not been seen since. The formal inauguration celebrations are of course well documented in sound and images, with the then-Chancellor Helmut Kohl as the most prominent political guest, the already seriously ill Herbert von Karajan, who nevertheless was not prepared to miss the inauguration of the hall and who, in honour of the chamber music atmosphere, conducted from the harpsichord, and Anne-Sophie Mutter as star violinist of the evening. Shortly afterwards, music critic Gerhard R. Koch reported on the spectacular evening in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (30 October 1987). His review is memorable as he alone took up the theme of movement in the space. Due to security concerns for the celebrity guests, there were stringent entry controls as well as allocated seating, but only for the official opening concert with Karajan and Anne-Sophie von Mutter. Thereafter, the concert opened up and became an opulent demonstration of the variety of possibilities the orchestra had at their disposal in the fluid, interlocking architecture of the Kemperplatz buildings.

Interconnected, fluid spatial concept

The Chamber Music Festival was intended to show not only the acoustics of the newly-constructed hall, but also to demonstrate the flexibility, porosity and internal connectedness of the spatial structure of the Philharmonie, the Musical Instrument Museum and the Chamber Music Hall. So the audience moved from the new hall through the foyer to the Philharmonie, then on to the Musical Instrument Museum and back, constantly attracted and seduced by the numerous chamber music ensembles and groups from within and outwith the orchestra. Among the more unusual aspects of the day was that apparently, even during the musical performances in the Chamber Music Hall, people moved around, from Block A near the podium up to the three legendary music galleries in order to test the acoustics of each piece. The strictly symmetrical internal spatial structure of the Chamber Music Hall had developed from these galleries and central hexagonal podium; both elements were fundamental to Wisniewski’s design concept. Under normal concert conditions, such wandering and moving around to experience the music is hardly imaginable. And yet, it corresponds in a strangely exact way – in the rhetoric of Scharoun and Wisniewski, it must be added, – to the thinking behind the architecture of both the Chamber Music Hall and the Philharmonie.

Too large?

Even in an article celebrating the birthday of the Chamber Music Hall, two awkward – or let’s say sensitive issues have to be touched upon: Not the costs, which increased five-fold in typical Berlin fashion during the construction period; after all, the final cost of almost 123 million DM (!) was ultimately well and sustainably invested. Rather, it is the size of the hall and its location. To many people, it seems too large and not as intimate, despite its acoustic qualities, as is expected of a chamber music hall, where – as Wisniewski put it – “a few friends of Beethoven or Schubert could look on over his shoulder as he plays a new piece.” Experience has shown that in normal concert usage, usually between a quarter and third of the seats remain empty. This corresponds to an average annual capacity utilisation of well over 60 percent. Looking at the original documentation, it is noticeable throughout that the Chamber Music Hall is significantly smaller in proportion to the Philharmonie in all competition models and photographs. Only in 1969 does the figure of 950 seats suddenly appear; according to Wisniewski, a number decided on by the then culture senator Werner Stein. This figure never seems to have been checked as is normally the case in the planning process, especially in such a long planning period. But it was never discussed again by the architect with his aesthetic values or by the city, which was responsible for the finances. Only during the design work was the number of seats increased to 1250, ultimately reaching today’s figure of 1136; only 200 more than originally planned, all the same. Apart from its impact on the urban space, another consequence of this is the continuous “circle of light” in the make-up of the hall, separating the upper and lower seating areas. This in turn gently contradicts the commandment proclaimed by Wisniewski and Scharoun regarding the “democratic enjoyment of music” of instinctively egalitarian music lovers.

A construction still “in the shadow of the Berlin Wall”

The second issue is the location of the Chamber Music Hall. Although it stands on the edge of the Tiergarten, an inner-city parkland, it is equally indisputable that, as Berliners say, it is very far away. Unfortunately, most of the Kulturforum has that feeling. This has been the urban development problem with the Kulturforum from the beginning, and which has never been satisfactorily resolved since the concept was formulated in 1964. Today’s international musicians who perform in the Chamber Music Hall, and who are used to jetting around the world, react enthusiastically to the hall and describe it as “unique”. However, they also spontaneously add how the shadow of the Berlin Wall still hangs over the whole of the Kulturforum. This is a response to the introverted and almost autistic urban atmosphere of the area which in the time of “West Berlin” stood facing the line separating East and West. What was then the East has, since the fall of the Berlin Wall, once again become the cultural and historical centre of the city.