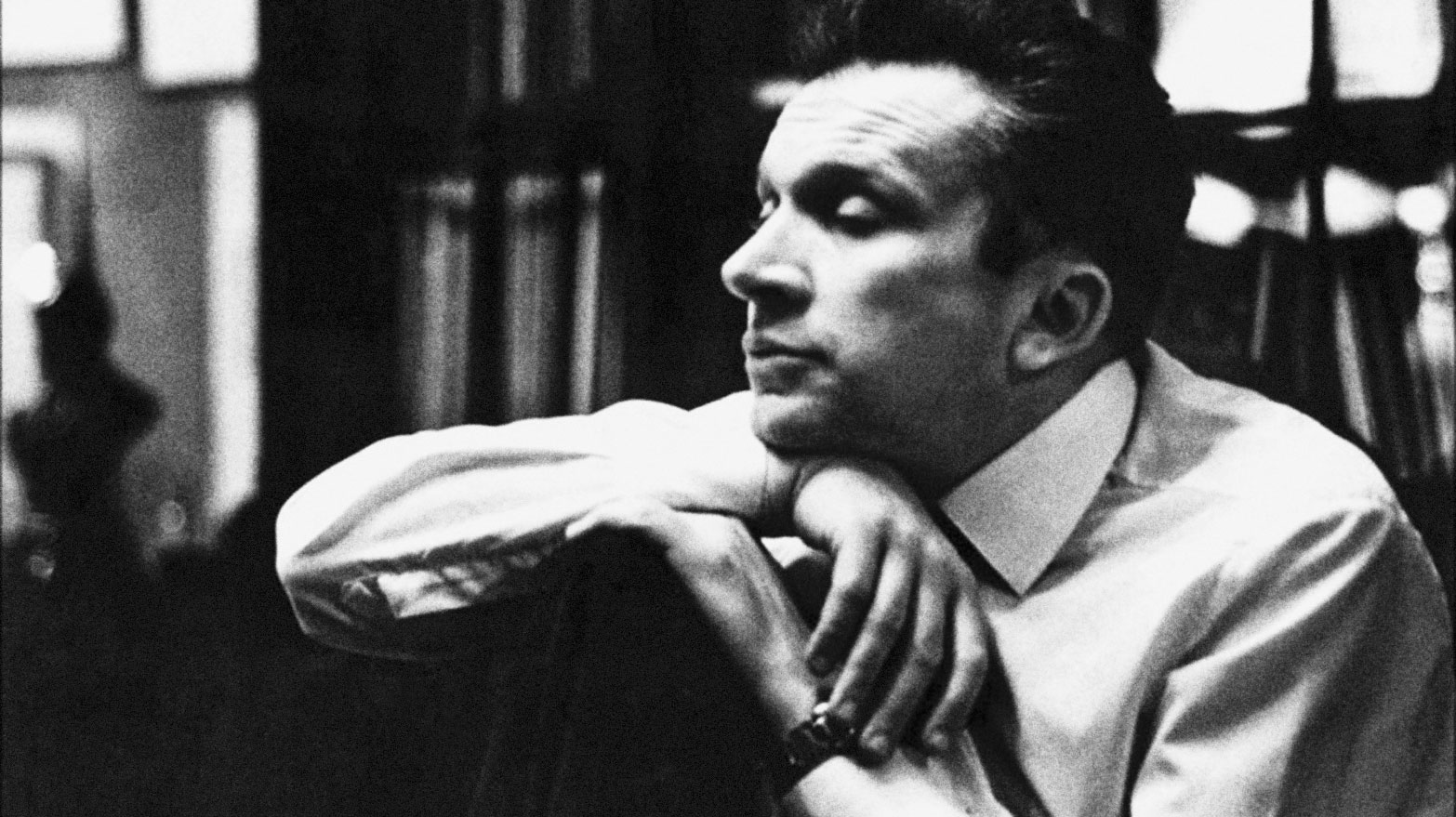

- Portrait

- History

The composer Mieczysław Weinberg is one of the great unknowns of the 20th century. His Trumpet Concerto is a work of exuberant virtuosity and ambiguous irony.

What a fate! What an oeuvre! The name Mieczysław Weinberg spread like wildfire when the Western cultural scene discovered him ten years ago. The staged premiere of his opera The Passenger at the Bregenz Festival in 2010 turned out to be a sensation; the work was acclaimed as a “masterwork”, the “rediscovery of the year”, if not the decade.

Bregenz passed its highly praised production on to London, Warsaw and Madrid; it was also presented in New York and Chicago. It took three years before the German premiere was held in Karlsruhe, however. Frankfurt, Gelsenkirchen and Graz followed – not exactly hotbeds of operatic activity, but in the meantime hardly a season goes by in which The Passenger does not turn up on some courageous stage or other.

Who was this composer whose name was suddenly the talk of the town? The various spellings “Mieczysław” or “Moisey” Weinberg, also “Vainberg” or “Vaynberg” – the result of transliteration from Cyrillic – already indicate complex roots and identities. His Russian friends from Shostakovich’s circle called him “Moisey Samuilovich”, a kind of “slavization” since, based on his father’s name, Weinberg went by the name “Samuilovich” in the Soviet Union. The fact that the designations as “Jewish”, “Soviet” and “Polish-Russian” composer are sometimes confused also reveals a certain bewilderment – or different perspectives.

Weinberg himself attached great importance to his Polish first name, with which he signed all his works, the only documents that accompanied him on his various escape routes. Above all, however, he hoped that his daughter Anna would have fewer problems in the increasingly anti-Semitic climate of the Stalin era as Anna Mieczysławovna than as Anna Moisyevna.

Through different worlds of happiness and horror

Like his Passenger, Weinberg also travelled through different worlds of happiness and horror; he was a passenger himself, as it were. He was born in Warsaw in 1919, the son of a theatre musician who was also the temporary director of the Jewish music department of the record company Syrena. His earliest musical experiences were operettas and music hall songs, Jewish and Polish dance rhythms and melodies – Moisey was always at the theatre from the time he was six.

He entered the Warsaw Conservatory at the age of twelve and two years later began his studies with Józef Turczyński, known today as one of the editors of the Paderewski edition of Chopin’s complete piano works and Poland’s most prominent piano teacher at that time. Weinberg also wrote his earliest compositions during this period – brief mazurkas, signed with the name Mieczysław for the first time.

The young student earned his money with improvisations at the elegant Warsaw restaurant Adria. When he was able to audition for the famous pianist Josef Hofmann, who invited him to continue his studies at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, his career as a piano virtuoso seemed assured. That was only a few months before the outbreak of the war, during which Warsaw would be levelled.

Thus, the – in Weinberg’s recollections – “best and happiest time” of his life was shattered. While fleeing from Nazi troops, he lost his father and sister. Safe in the Belarus capital of Minsk, he studied composition with Vassily Zolotaryov, but a few days after his final exams, he was again forced to flee from the German attack on the Soviet Union. He reached Tashkent, the capital of the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan, and from there moved to Moscow at Shostakovich’s invitation. He remained there until his death in 1996.

“a fine composer, a good man with upright character, but definitely too modest”

Shostakovich was the great stroke of luck in Weinberg’s life: he had sent his First Symphony to the celebrated Russian composer in 1943 and, in response, received warm approval. A lifelong friendship developed, full of mutual esteem, solidarity and inspiration. Shostakovich’s support was a source of constant encouragement for the sensitive, shy Weinberg – “a fine composer, a good man with upright character, but definitely too modest”, Shostakovich said of him.

Shostakovich tirelessly championed the performance of Weinberg’s works, was his advocate during the verbal attacks by the Composers’ Union and made sure that his friends, the world’s best interpreters, performed his works: Mstislav Rostropovich, David Oistrakh, Leonid Kogan, Rudolf Barshai. The oft-repeated statement that Weinberg was Shostakovich’s student – as a result of which he was often mistaken for a second-rate imitator – must be revised in order to clarify that there was learning on both sides.

Shostakovich passed his fascination with Mahler on to his 13-year-younger colleague, who supplied Shostakovich with information about Jewish folklore. Its echo is heard most clearly in the Russian composer’s Piano Trio op. 67 and his song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. There was a regular competition between the two composers over the production of string quartets; in the end, Shostakovich wrote 15, Weinberg 17.

The musical affinity went so far that, according to an account of his wife, Weinberg dreamed of themes which then actually appeared in Shostakovich’s music. The four-hand performances of their works with the two friends at the piano were legendary; they were thus able to make their symphonies, including those that were never performed, accessible to select circles.

Both were caught in the machinery of Stalinist cultural policy. Works by Weinberg that were highly praised at first, such as the Sinfonietta or the Sixth String Quartet, were denounced as “formalist” or “nationalistic” a short time later.

The Passenger, which quite unemotionally protests the hell of Auschwitz and yet allows humanity to emerge in remembrance, was condemned as “abstract humanism”. Stalin’s henchmen did not even spare the composer himself. After the murder of his father-in-law, who was suspected of enemy activities, Weinberg was imprisoned for four months. It is uncertain whether he was released because of Shostakovich’s courageous letter to the authorities or Stalin’s death.

More than 150 works, including several operas, 21 symphonies and 17 string quartets

Weinberg’s productivity and creativity border on a miracle in view of such personal circumstances. More than 150 works, including several operas, 21 symphonies and 17 string quartets, are the result of a continuous, almost driven creative process, as though this was also a flight from the terrors he suffered.

Nevertheless, the composer grappled with his fate again and again. Numerous “anti-war works”, with deep sorrow rather than a propagandistic moralizing tone, are found in his oeuvre. And yet there is always tenderness, wit and irony as well, not as harsh and bitter as many works of his friend Shostakovich.

The brief opera Congratulations is brimming with colourful humour with a rebellious undertone. The Trumpet Concerto op. 94, which the Berliner Philharmoniker, Andris Nelsons and Håkan Hardenberger deservedly rescue from oblivion, also exudes sparkling wit. But here as well, the trumpet displays almost nostalgic klezmer qualities with thoughtful interpolations.

In the case of each of these Weinberg works, which one encounters more or less by chance, it is inconceivable that they are not an integral part of the concert repertoire. The reasons may lie, for one thing, in Weinberg’s personality. He was incapable of self-promotion; the persecution he suffered made him withdraw with even more anxiety than before. Prominent interpreters, such as Barshai and Kondrashin, emigrated to the West, where they were not able to champion the unknown composer, who had not followed the prevailing trend of modernity.

The cold war made an anathema of almost all composers who were not clearly “dissidents”, and after the fall of the Soviet Union, a confrontation with socialist realism, with all of its creative and in varying degrees overt offences, was less desirable than ever. Only the anti-war drama The Cranes Are Flying, with Weinberg’s wonderful soundtrack, which won the Golden Palm at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival, caused a sensation.

For the 100th anniversary of the composer’s birth in 2019, there were Weinberg festivals, symposia and concerts. Linus Roth and Thomas Sanderling from the Weinberg Society are committed to the promotion of the composer’s works, approximately two-thirds of which are well-documented on historical and modern CDs. But on a concert scene that attempts to satisfy the presumed tastes of listeners with the same masterworks over and over again, unfamiliar works hardly have a chance to become permanently established beyond a brief sensational success.

“When the echo of their voices dies away, we will perish” is the conclusion of The Passenger. That also applies to its composer Moisey Mieczysław Weinberg.